“I think that’s the main draw of it: You can make anything a reality,” Laming said in an interview with CNN Business.

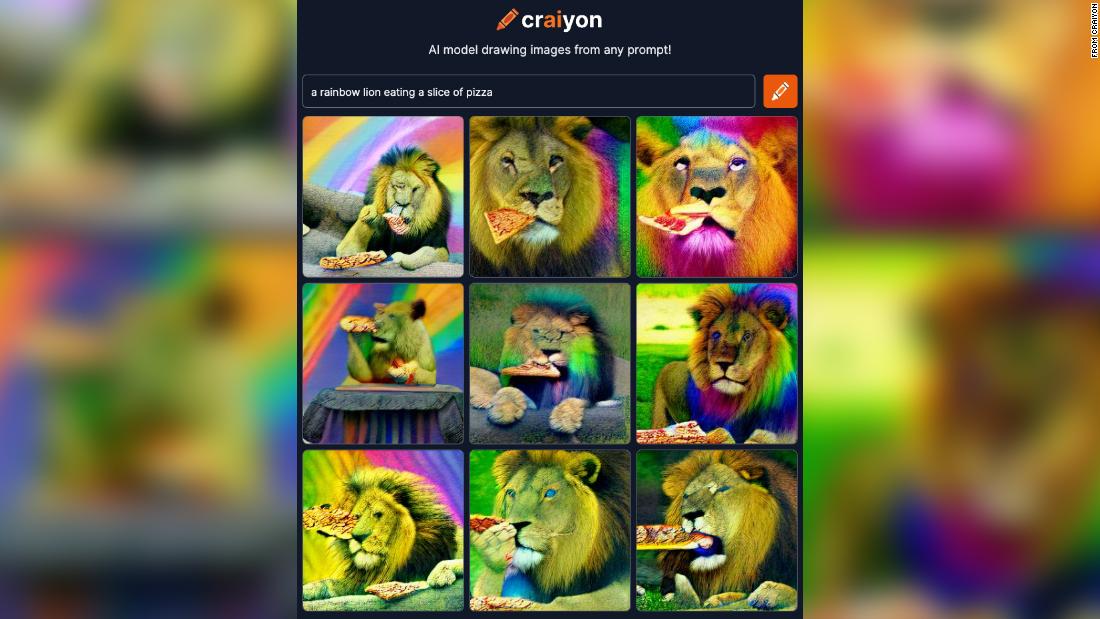

The brainchild of Boris Dayma, an Austin-based machine-learning engineer, Craiyon is popularizing a growing trend in AI. Computers are getting better and better at ingesting words and producing increasingly realistic-looking images in response. Lately, people are typing in about 5 million prompts per day, Dayma said.

There are similar, much more powerful AI systems than Craiyon, such as OpenAI’s DALL-E (Craiyon was initially named DALL-E Mini as an homage) and DALL-E 2, as well as Google’s Imagen. But unlike Craiyon, which anyone can try, most of these are not available to the public: DALL-E 2 is open to users via invitation only, while Imagen has not been opened up to users outside Google.

“I think it’s important to be able to have an alternative where everybody has the same access to this type of technology,” Dayma said.

In the process, however, Craiyon is effectively acting as a trial run for what could happen — good or bad — in the future if anyone can access such AI systems and solicit any kind of image from them with just a few words. And as with many nascent technologies, it is a work in progress; in the near term, if left unchecked, it may produce outcomes that reinforce stereotypes and biases.

The Notorious BFG

In the past, for example, it would be able to envision simple things like a landscape, Dayma said. But little by little, he’s done things such as fixing bugs and improving code, enabling it to get better at coming up with more complicated images, such as the Eiffel Tower landing on the moon.

“When the model started drawing that, I was very happy,” he said. “But then people came up with things even more creative, and somehow the model reached a moment where it was able to do something that looked like what they asked for, and I think that was a turning point.”

The images Craiyon generates are not nearly as realistic-looking as what DALL-E 2 or Imagen can come up with, but they’re fascinating nonetheless: People tend to blur into objects, and images look fuzzy and at least slightly askew.

For now, Craiyon is mostly being used for fun by people like Laming — perhaps in part because its results are not nearly as crisp or photorealistic as the images you can get from DALL-E 2 or Imagen, but also because people are still trying to figure out what to do with it. (The Craiyon website currently runs ads to recoup costs for the servers that power the AI system, and Dayma said he’s trying to figure out how to make money from it while also allowing people to play with it for free.)

To come up with a good prompt, Laming suggested, just “think of the most outlandish situation to put someone or something in.” In effect, the prompts that lead to these pictures are themselves arguably a new form of creativity.

Biases on display

Mar Hicks, an associate professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology who studies the history of technology, said this AI system reminds them of early chatbots such as Eliza, a computer program built by MIT professor Joseph Weizenbaum in the 1960s and meant to mimic a therapist. Such programs could convince people they were communicating with another human, even though the computer didn’t truly understand what it was being told (Eliza gave scripted responses).

“I think it’s appealing the same way that a game of chance is appealing, or a party game,” Hicks said. “Where there’s some level of uncertainty about what’s going to happen.”

Dayma said he’s heard from people using Craiyon to come up with a logo for a new business and as imagery in videos. (OpenAI and Google have suggested that their systems might eventually be used for things like image editing and generating stock images.)

While there may be creative possibilities for these AI systems, they share a key problem that pervades the AI industry at large: bias. They’re all trained on data that includes wide swaths of the internet, which means the images they create can also lay bare a host of biases including gender, racial, and social stereotypes.

Such biases are evident even in Craiyon’s fuzzy-looking images. And because anyone can type anything they want into it, it can be a disturbing window into how stereotypes can seep into AI. I recently gave Craiyon the prompt “a lawyer”, for instance, and the results were all blurry images of what appeared to be men in black judge’s robes. The prompt “a teacher,” meanwhile, yielded only figures that appeared to be women, each in a button-down shirt.

He also said that he tried to prevent the model behind Craiyon from learning certain concepts to start with. However, it only took me a few minutes to come up with some explicit prompts that yielded images that are, to put it bluntly, not safe for work.

Asked whether he thinks its general availability could be a bad thing, given its obvious biases, he pointed out that the images it comes up with, while better-looking than in the past, are clearly not realistic.

“If I draw the Eiffel Tower on the moon, I hope nobody believes the Eiffel Tower is really on the moon,” he said.