Reviewing a European art show in 1891, the Belgian poet and art critic Émile Verhaeren remarked that there were no longer movements or groups, only fast-shifting rival tendencies like “kaleidoscopic geometric patterns, which clash at one moment only to unite at another . . . fuse and then separate and fly apart . . . but which all nevertheless revolve within the same circle, that of the new art”.

What was the new art? In the magnificently rich, bewildering epoch between the final Impressionist exhibition in 1886 and the first world war, opportunities created by the invention of Impressionism attracted hundreds of impassioned artists, swooping into Paris, circling Berlin, Vienna, Munich, each convinced of their own true vision. It’s a marvellous subject, and the National Gallery’s overview After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art is engrossing, enjoyable and instructive, starting and finishing with superb parades of some of the era’s greatest hits.

Sumptuous and abundant, the large opening gallery is lit by Cézanne’s translucent amplitude — the flickering dabs and cubes of “Mont Sainte-Victoire”, “Bathers” grandly fused with their forest surroundings, precariously tilting objects in “Sugar Bowl, Pears and Tablecloth” — and by Van Gogh’s ecstatic-tormented responses to Provence.

A highlight is a quartet of little-known Van Goghs from private collections, led by “Landscape with Ploughman”, the view from the Saint-Rémy asylum of a yellow stubble wheat field and thick purplish earth beneath a huge sun “that floods everything with a light of fine gold”, as the artist wrote. The group also includes the most beautiful of the six simplified, tender-sombre “L’Arlésienne” portraits, depicting Madame Ginoux, proprietress of Arles’ Café de la Gare; only in this version are the flat pink-green contrasts of costume and face wonderfully animated by a pulsing floral background.

The dark notes in this section are Gauguin’s. The uneasy nude “Nevermore”, Tahitian fantasy made real, a painting of sexual and colonial oppression, is now intensely problematic. But two rarely shown 1888 paintings compel for their differing, charged inspirations: “Fête Gloanec”, a strange floating still life of Breton cakes and fruit on a black-rimmed table, pays homage to Cézanne, while “The Wave”, a dizzying, almost vertical seascape of rocks and eddies, derives from Monet’s scintillating, plunging Belle Île paintings, exhibited in 1887.

Among critics of these was anarchist Félix Fénéon, who complained that Monet tended to “make nature grimace” — that Impressionist landscape, twisting into ever higher distortions, had run out of steam. Van Gogh, studying Monet’s sinuous comma strokes and liberated colour in 1886-88, would assimilate them into his own emotive landscapes to become the father of Expressionism, proving Fénéon wrong. But, meanwhile, Fénéon’s anarchist friends Georges Seurat and Paul Signac transformed Impressionist emphasis on pure colour, light and form into something systematic, structured and impersonal — the stiff geometry of pointillism.

In Seurat’s serene, though painstaking, “The Channel of Gravelines” (1890), the shore in morning light, a strip of sea, broad horizontal planes of sand and sky balanced by thin verticals of masts and signal tower mesh into a mosaic of luminous dots. In Signac’s “Setting Sun. Sardine Fishing. Adagio.” (1891), gradations of colour shimmer on gently swelling water, boats lined up against the sunset — joyous.

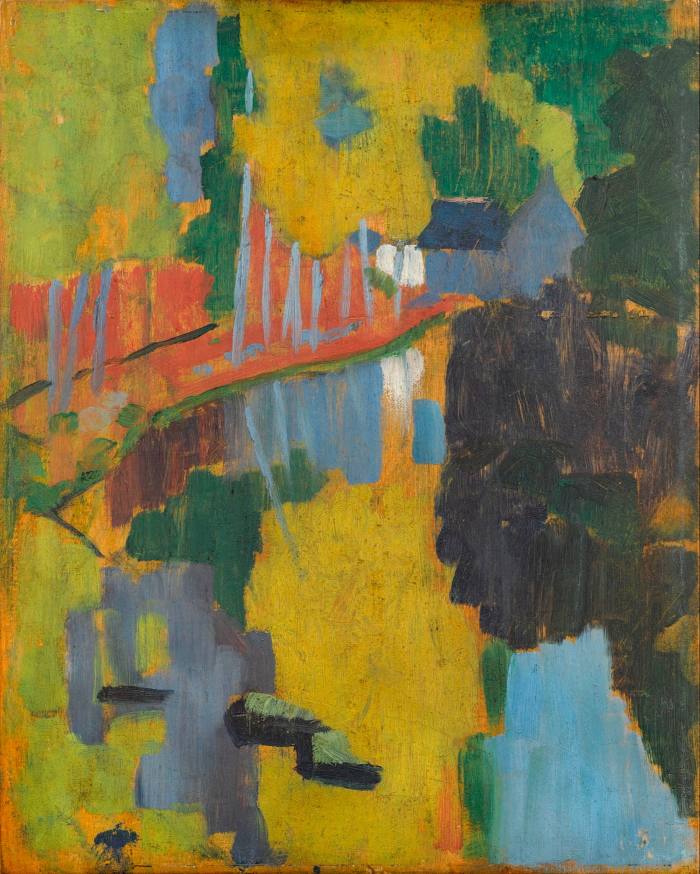

The anarchists’ quest for order on canvas may seem paradoxical, but favouring the mechanical dot over individualist brushstrokes was a political gesture. Opposing it was Maurice Denis, Catholic self-styled “neo-traditionalist” and focal figure for the loosely affiliated Nabis (Prophets) painters. The work they named “The Talisman”, visiting here from the Musée d’Orsay, was Paul Sérusier’s 1888 sketch of a landscape as patches of yellow and blue. Denis acquired it and in 1890 published the clarion call that modern painting be “a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order”.

Already in the 1870s, perceptive commentators understood that the subjectivity of Impressionist rendering opened the path to abstraction; in the 1890s and 1900s, the path became a multi-lane highway, frequented by fascinatingly varied vehicles. Though jumbled and uneven, the central section here does evoke the kaleidoscopic confusion Verhaeren described — an everything everywhere all at once decade.

In Paris, “Figures in an Interior: Music”, Vuillard’s panel of pianist, listeners and flowers dissolving into wallpaper, was painted in pigment mixed with glue to emulate chalky ancient friezes, and also recalls medieval tapestry — while simultaneously anticipating all-over abstraction. In Vienna, Klimt in “Hermine Gallia” filled a canvas with a dress as surface ornament, influenced by Byzantine decor. In Moscow in 1895, Kandinsky saw a Monet: “That it was a haystack, the catalogue informed me. I didn’t recognise it . . . objects were discredited.” He imagined landscape as pure shapes and marks: here the houses and hills abbreviated into stripes and streaks in “Bavarian Village with Field”.

This sole Kandinsky is a poor example, and one disappointment here is the scant non-Parisian art. Italian and Russian futurism are wholly absent. Under the heading “New Voices: Barcelona & Brussels”, a meaninglessly random pairing, Picasso (already in Paris) blasts everyone else off the wall with the electrifying nocturnal portrait of moustache-twirling “Gustave Coquiot” (1901) at a Montmartre nightclub. The section on German and Austrian Modernism omits the two great radicals Egon Schiele, Klimt’s psychologically devastating successor in extreme linearity, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, leader from 1905 of Expressionist group Die Brücke. The German paintings offered instead, such as Max Pechstein’s “Charlotte Cuhrt” in altarpiece frame, acquired by the National Gallery last year, are mostly feeble.

Concluding back in Paris, the show recovers, and occasionally astonishes. André Derain’s gloriously strident “The Dance”, spinning with a snake across a jungle, demonstrates influences from Gabon masks, Javanese temple sculptures, Romanesque drapery — a fantastic melee and a quite unknown work. Matisse’s “Interior with a Young Girl”, his daughter calmly reading in a room aflame with hot contrasting hues and overwhelming decorative patterning, is a stunning Fauve loan from MoMA. Braque’s “Castle at La Roche-Guyon”, the building climbing the canvas as separate walls and roofs, and Picasso’s “Woman with Pears”, his lover Fernande Olivier’s head splintered into fragments, both 1909, classically unpack Cézanne into cubism.

To display such canonical art history — the trio of Cézanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin, who were so foundational for Picasso, Matisse, the 20th century — is an achievement in the UK: the important collections are in France and the US. But since John Rewald defined this lineage in the 1940s and 1950s, fresh vistas have complicated the picture — not only beyond Paris but also understanding later works by the Impressionists themselves. It’s perverse to include Degas here, yet not Pissarro, bridge to pointillism, or Monet, who paralleled Cubist experiments in the discontinuous space and jagged rhythms of his “Water Lilies”, subject of a celebrated 1909 Paris show. This is a good, steady exhibition; a wider lens would have made it a great one.

To August 13, nationalgallery.org.uk

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter