On International Riesling Day, six top wine producers came to London to demonstrate the unique qualities of fine German wine and how well it ages. Their tasting featured not just Riesling but the more recently emergent red Pinot Noir (Spätburgunder in German). They had each decided to show three vintages of one of their top wines, one from the 1990s, one from the 2000s and one from the 2010s.

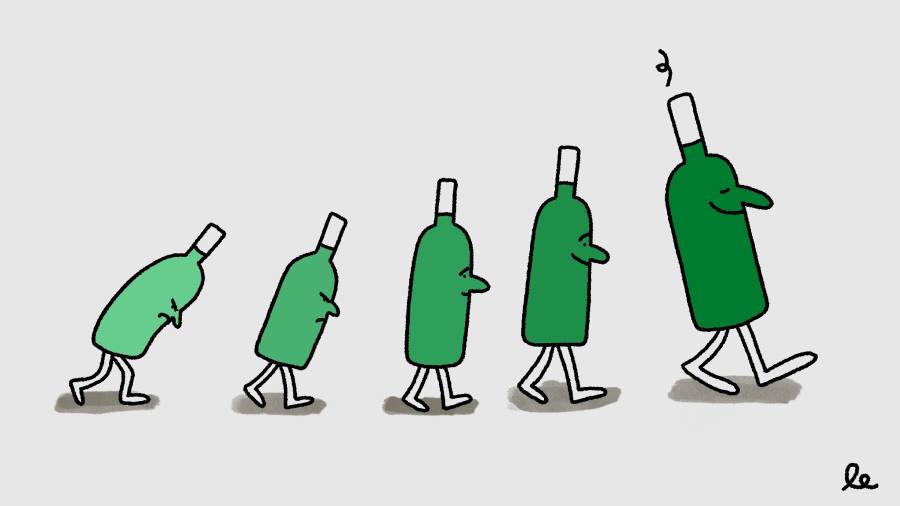

German wine has completely transformed itself in recent years, but fine wine buyers seem stubbornly unaware of the fact. See the prices below for the crown jewels of German wine that were shown in London. Even The Wine Society in the UK, whose members are more traditionally minded than most wine consumers, and absolutely lap up red bordeaux at all price levels, finds Riesling a hard sell.

Part of the reason is that there is hardly any secondary market to speak of. This is why the tasting was needed – to show people who don’t have German wines in their cellars the virtues of decades-old Riesling and Spätburgunder.

Germany’s top producers are family affairs with much, much smaller landholdings than the typical Bordeaux château, for instance. And instead of making just one or two wines a year as Bordeaux producers do, most of them make a wide range of wines from various different vineyards (a bit like Burgundy) but also of varying degrees of ripeness. So each wine tends to be made in relatively small quantities. No wonder they are not major features on the lists of fine wine traders and auction houses.

There is also the fact that there has not been a tradition among German wine producers of keeping older vintages for late release at a higher price. That said, one of the six who came to London, Dorothee Zilliken of the cool, wet Saar valley, explained that her grandfather, most unusually, was in the habit of putting half of each year’s production straight into the family cellar and that this had stood them in very good stead financially over the years.

Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Zachys may almost ignore German wine, but Germany itself does have a series of fine wine auctions each September, where such wines are finally offered. Zilliken is apparently looking forward to presenting the oldest wine in the family cellar, a Saarburger Rausch 1949, at her local auction in Trier in its centenary year.

The London tasting was the idea of Zilliken (of Forstmeister Geltz-Zilliken), Cornelius Dönnhoff of the Nahe, Theresa Breuer of Georg Breuer in the Rheingau (all of them showing their family’s Rieslings) and Joachim Heger of Baden, Stephan Knipser of Pfalz and Sebastian Fürst of Franken (all presenting Pinot Noirs). In the past I have argued that one of the reasons that German wine has been losing ground on export markets is that the producers don’t travel enough. I shall have to shut up.

The producers invited two independent German wine writers to co-host the event with them. Ulrich Sautter of Falstaff magazine came over from Germany with the producers and gave us some background on soil types and the like.

Anne Krebiehl, the only German Master of Wine living in the UK, reminded us of how recently the status of German wine had changed within Germany itself. “People forget the doldrums of German wine, especially from about 1985 to 1995. If you were cool in Germany then, you didn’t drink German wine,” she said. “But it has changed this century. It happened with dry Riesling first, then Pinot,” she said. “And now it’s finally happening with Sekt,” she added referring to the German sparkling wine.”

That word “dry” is important. German wine won new fans on the German market when it turned its back on the medium dry and sweet wines that used to proliferate and started offering well-made wines described as trocken, or dry. Even The Wine Society now sells as much dry German wine as sweet. But old prejudices linger.

Breuer, who makes beautifully balanced dry Rieslings, reported that she is still fighting German visitors who arrive complaining that “Riesling is so acid”, and non-German tourists who are still convinced that “Riesling is so sweet”.

They are out of touch. German wines have improved immeasurably in the past two decades, major beneficiaries of the warming climate that now results in fully ripe grapes without the searing acidity of the last century that had to be compensated for by sweetness. As we discovered during the tasting, this has resulted in a complete change of strategy when making wine.

It is a fact of human nature to value what is most difficult to achieve. So the infamous German Wine Law of 1971 not only redrew the map so that wines were easier to sell rather than better to drink, but prioritised (natural) sweetness, so the sweetest wines were the most valuable. Degrees Oechsle, the name given to the German scale traditionally used to measure grape ripeness, were as Krebiehl put it “fetishised”.

But today, especially in hot summers such as 2018 and 2022, wine grapes in German vineyards can easily get too ripe, and even sunburnt. Modern viticultural techniques include carefully trellising the vines so that the grapes are shaded during the height of summer.

Cornelius Dönnhoff explained about his celebrated winemaker father Helmut, “My father was fighting for ripeness and now I’m the opposite. He comes into the vineyard and thinks everything we’re doing is wrong.” As he explained when presenting the 1994 vintage of Dönnhoff’s dry Niederhausen Hermannshöhle Riesling Spätlese, the grapes were picked in the third week of November, and all the best grapes were reserved for sweet wines, which was quite common then. Nowadays they start picking the grapes for this wine in mid-September.

Another major development occurred as early as 2002, when the elite German wine producers’ association, the VDP, came up with their top category of wine, Grosses Gewächs, dry wines from specified vineyards they rated the best, a move in a sort of Burgundian direction. This was before the major move to freshness and lightness and for some years German producers outdid themselves to see who could make the most powerful and, in the case of the various Pinots, oakiest wine. But this era has now passed, thank goodness, and most fine German wines today are beautifully balanced.

It was interesting that five of the six producers chose to show us dry wines, with only Zilliken favouring three vintages of her featherlight (8 per cent alcohol), ethereally fruity Saarburg Rausch Riesling Auslese Goldkaspel, a speciality of her region. According to her, “The wines are so vivid they act like a shot of espresso! Some will last longer than me.”

She ended the tasting with a rallying cry to her fellow winemakers. “We all stand for something very special. That’s Germany!” She’s absolutely right.

Crown jewels of German wine

Dr Heger, Winklerberg Spätburgunder Grosses Gewächs, Baden

1997, 2008, 2015 shown. Average price £52Knipser, Kirschgarten Spätburgunder Grosses Gewächs, Pfalz

1991, 2009, 2015 shown. Average price £37Fürst, Centgrafenberg Spätburgunder Grosses Gewächs, Franken

1997, 2010, 2016 shown. Average price £80Georg Breuer, Berg Schlossberg Riesling Qualitätswein trocken, Rheingau

1993, 2002, 2012 shown. The 2020 is £85 The Sourcing TableDönnhoff, Hermannshöhle Riesling Grosses Gewächs, Nahe

1994, 2010, 2016 shown. Average price £77Forstmeister Geltz-Zilliken, Saarburg Rausch Riesling Auslese Goldkapsel

1997, 2005, 2010 shown. Average price £106

Tasting notes on Purple Pages of JancisRobinson.com. Follow Jancis on Twitter @JancisRobinson

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first