When Nicola Sturgeon launched an advanced new ferry from the last civilian shipbuilder on the Clyde in 2017, Scotland’s first minister hailed the event as an important moment for her nation’s engineering and manufacturing reputation and its overall economy.

More than five years later, the Glen Sannox ferry — which it turned out had been launched with its bridge windows only painted on — is unfinished and vastly over budget.

For critics of Sturgeon, who will step down on Monday, the sorry tale of the Glen Sannox would make a fitting metaphor for her eight years as head of Scotland’s devolved government, a period in which they say she has overpromised and underdelivered.

James Mitchell, professor of public policy at Edinburgh university, said Sturgeon had failed to exploit the political opportunity she enjoyed when she took over as first minister in the aftermath of the 2014 referendum in which Scots voted backed staying in the UK by 55-45 per cent.

“Her record in government, frankly, is not good,” said Mitchell, co-editor of a 2016 book on leaders of Sturgeon’s pro-independence Scottish National party.

In valedictory appearances this week, Sturgeon, 52, who even opponents say is one of the most effective UK politicians of her generation, dismissed suggestions her career was ending in failure. The first minister highlighted the SNP’s eight successive election victories under her leadership and hefty current lead in opinion polls.

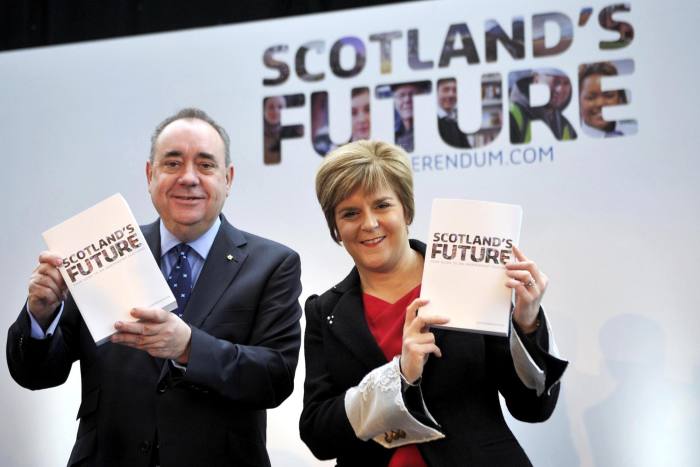

Since she succeeded Alex Salmond as first minister in 2014, the SNP government has shifted to the left, sharpening the contrast with the Conservative UK government. Most strikingly, Sturgeon used newly devolved powers to make income tax rates more progressive and social security more generous.

The tax and benefit changes mean the richest 10 per cent of Scottish households will be £2,590 poorer in the coming fiscal year than English and Welsh counterparts with the same income, but the poorest 10 per cent will be £580 better off, according to the independent think-tank the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

The introduction of a £25-a-week child payment scheme is helping low income families in particular. “If I had to single out the thing I am proudest of, it is that: helping to lift children out of poverty,” Sturgeon said.

The coronavirus pandemic is likely to be remembered as Sturgeon’s finest hour. Daily televised briefings showcased the empathetic communication skills central to the success of the once shy and bookish schoolgirl from a working-class family who joined the SNP aged 16.

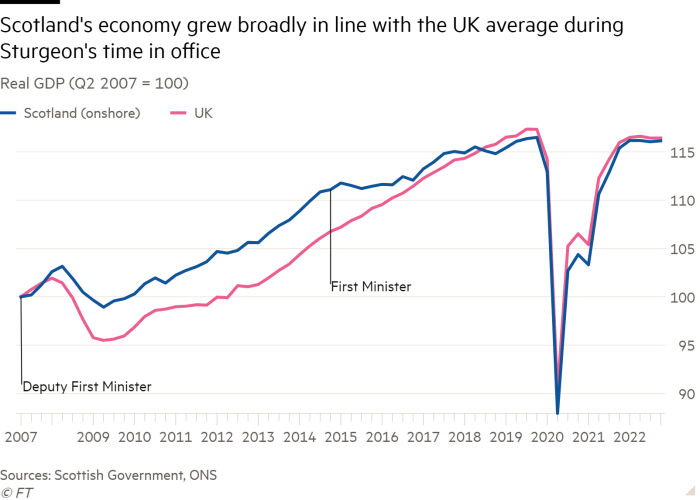

But Sturgeon’s coronavirus policies differed from those of the UK government in England mainly in details of timing and tone, and Scotland’s overall record in terms of deaths and economic damage are similar — and unimpressive compared with European peers.

And while Sturgeon blames the pandemic for the woes of the Scottish health system, it was under serious strain even before 2020. After 16 years of SNP rule, Scotland has lower and falling life expectancy and higher deaths from drug misuse than England and other European peers.

Asked about soaring drug-related deaths in a 2021 election debate, Sturgeon was frank. “I think we took our eye off the ball,” she said.

Some analysts said that Sturgeon’s relative political caution had limited her impact.

The SNP came to power in 2007 promising to scrap the “unfair” property-based council tax paid to local authorities. But in 2015, Sturgeon merely tweaked council tax rates and left in place the quarter-century valuations on which they are based.

She was bolder in her ambition to close the yawning gap in educational attainment between richer and poorer pupils, declaring in 2015 that this was the issue she wanted her first ministership to be judged on.

But her government dropped legislation giving schools more autonomy in 2018. The Scottish Attainment Challenge, a government-funded scheme, says the gap remains “unacceptable”.

Sturgeon’s promotion of trans rights, including with legislation making it easier to gain official recognition for changes of gender, has angered some who believe it puts women’s sex-based rights at risk. Author JK Rowling has called Sturgeon a “destroyer of women’s rights”.

Others praise the first minister, who has appointed gender-balanced cabinets since 2014. “Women, girls and LGBT people in particular have a lot to thank her for in terms of protection and advancement of their rights,” said Kezia Dugdale, director at the John Smith Centre, which promotes trust in politics.

But Dugdale, Scottish Labour leader from 2015 to 2017, said Sturgeon’s overriding goal of Scottish independence had prevented her from taking a vested interest in areas such as education.

“Reform means upsetting apple carts,” said Dugdale. “Much of her tenure in office was about maintaining as broad a supporter base as possible in the hope of converting that into support for independence.”

Yet some independence supporters say lack of bolder reform also undermines the SNP claim that an independent Scotland would be better governed. And despite Sturgeon’s efforts to maintain the SNP’s broad church, she departs with Scotland broadly split down the middle on whether to end the three century-old union with England.

Sturgeon’s failure to raise support for independence to levels that would have pressured Westminster to drop its block on a second plebiscite meant Sturgeon’s legacy was “mixed”, said Michael Keating, emeritus professor of politics at Aberdeen university.

“Sustaining support for independence at around 50 per cent is an achievement that no other leader has done before, but on the other hand it is not enough,” Keating said.

“Whoever takes over is going to have to strike out in a different direction.”

Differences over independence strategy and issues such as gender recognition have fuelled strains on SNP unity created by a bitter feud between Sturgeon and Salmond, her former mentor.

The two fell out after female civil servants in 2018 accused Salmond of sexual harassment during his time as first minister. At a criminal trial in 2020, Salmond was acquitted of all 13 sexual offence charges against him.

A parliamentary committee later concluded that Sturgeon had misled it over how she learned about the allegations against Salmond, but a separate probe cleared her of breaching the ministerial code. She bounced back to lead the SNP to victory in 2021 Scottish elections, while Salmond’s new Alba party failed to win a single seat.

Sturgeon, who marked her 2014 accession to SNP leader with a rally of more than 10,000 joyous supporters in Glasgow’s biggest indoor music venue, leaves behind a party in much more sombre mood.

The candidates to succeed her have trashed each other’s record in government and long-serving SNP chief executive Peter Murrell, Sturgeon’s husband, stepped down after the party was forced to admit it had 30,000 fewer members than claimed.

The SNP’s struggle to refresh Scotland’s ageing ferry fleet has dented claims to competence central to its claim independence would lead to better government.

The cost of the Glen Sannox and a sister unfinished vessel has tripled to nearly £300mn after a process members of a parliamentary committee said this week was riddled with failures in transparency and accountability.

But while critics say Sturgeon’s record has fallen short of her rhetoric, the departing first minister is defiant, advising her successor in a farewell parliamentary statement not to “shy away from the big challenges”.

“You will not get everything right, but it is always better to aim high and fall short than not to try at all,” she said.