The party seems stuck in a dangerous political position of insisting the economy is doing well while voters think it’s in the tank.

“I’d like to take this opportunity to speak directly to the American people,” Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said at the start of a news conference. “Inflation is much too high, and we understand the hardship it is causing. We are moving expeditiously to bring it back down.”

Yet the strikingly direct moment may not quell concerns that the Fed and the White House have acted too slowly to tackle inflation, are not using sufficiently aggressive methods to ease it and may still be overtaken by global factors, including the war in Ukraine and the fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic, which clogged supply chains, sent energy prices soaring and triggered other rising prices.

What the interest rate hike means

The rate increase will make new home and car loans and payments on credit card balances more expensive. But in the process, it could cool the housing market, making it easier to buy a home and taking the heat out of rising prices.

Justin Wolfers, a professor of economics at the University of Michigan, explained that Americans could see results from the rate hikes in their daily lives, as inflation simmers at the highest levels since Ronald Reagan’s 1980s presidency.

“What the Fed is hoping to do is cool inflation a little so your paycheck will go a little further, although that will mean slowing the economy and that might mean a little less bargaining power for workers and fewer prospects of a wage rise anytime soon,” Wolfers said on CNN’s “Newsroom.”

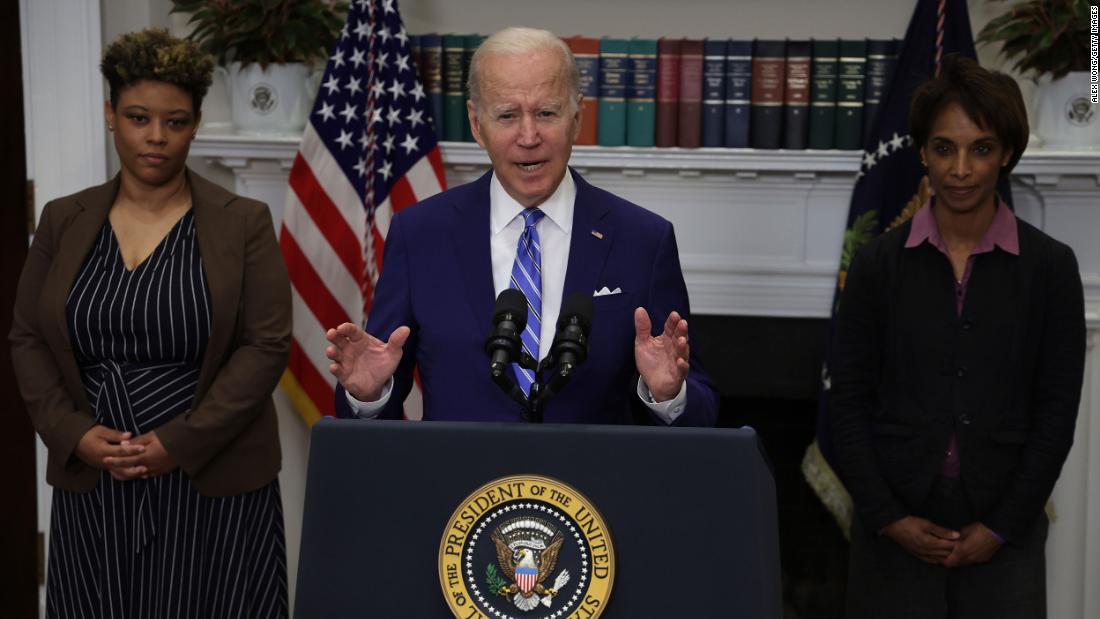

Biden, for example, on Wednesday touted cuts in the federal budget deficit and an unemployment rate that is approaching 50-year lows in a speech that appeared to be an attempt to get ahead of the Fed announcement and to signal resolve.

Yet his political plight is underscoring why inflation remains a force that is dreaded by political leaders everywhere.

Despite Republican claims in midterm campaign ads that Biden’s public spending policies are the sole cause of inflation, the President is correct to identify outside factors, including the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, as the main drivers of rising prices.

But the reality doesn’t mean voters will give Biden a pass. It’s the nature of the job that when the country is in a grim mood, the President gets the blame. And when the White House’s efforts to explain the problems and fix them have sometimes been muddled and too late, the political damage mounts. Biden may never shake off the initial White House line that high inflation was a “transitory” phase coming out of the pandemic. And while the economy is strong in many areas, voters’ perception is often more important politically than the data that tells the real story.

A daunting poll for the White House

The CNN poll, for example, says that only 23% of Americans rate economic conditions as even somewhat good, down from 37% in December. The last time public perception of the economy was this poor in CNN’s polling was November 2011. Only 34% approve of Biden’s management of the economy. And his approval rating on helping the middle class — 36% — is devastating for a President who has made that issue the foundation of his political career.

The question of public perception versus the true state of the economy is also borne out in the poll. Americans said by nearly 4 to 1 that they were more likely to hear bad news than good news about the economy.

Some 94% of Republicans rate economic conditions as poor. This suggests that views of the economy may be shaped by partisan leanings as much as a neutral judgment of conditions. Conservative news channels keep a constant drumbeat of horror stories about rising prices, and Republicans have made the issue an effective campaign tool while hyping the strength of ex-President Donald Trump’s economic performance.

Yet 81% of independents and 54% of Democrats also think the economy is poor, suggesting that Biden has taken a hit among some of the voters who put him in office.

Americans are more positive about their own finances than about the national economic situation, with 53% saying they’re satisfied with their personal financial situations. That could again indicate that a wider sense of malaise is coloring views of the economy. Still, that figure is down from 66% in 2016.

Given this catalog of gloom, Biden’s tone and topic on Wednesday were a little surprising.

He claimed credit for a $1.5 trillion cut in the federal deficit by the end of the year. This compares with the profligacy of the debt-laden Trump years and exposes the hypocrisy of Republican deficit hawks who forget their supposed principles when one of their own is in the Oval Office.

Yet how many Americans stretching their weekly budgets care that much about deficits — even if, as Biden said, lowering them could bring down inflation in the long term?

The White House event also exposed the President’s frustration that he’s not getting credit for what’s good about the economy.

When a reporter asked him about Ukraine and the Supreme Court’s abortion drama, he replied: “No one asked about deficits, huh? … You want to make sure this doesn’t get covered.”

What happens next

The best hope for Biden, other Democratic politicians and all Americans facing an economic crunch is that the Fed’s approach works and prices fall. And some perspective here: The economy isn’t facing the full-blown disaster of 2008 or even the inflationary nightmares of 40 years ago.

“I don’t think we have the economy of the 1980s or the 1970s,” Betsey Stevenson, who was a member of President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, said on “The Lead with Jake Tapper” on Wednesday.

But it’s hard to see how things get better quickly — or anywhere near in time to make a difference to Biden before the midterms.

Even if the war in Ukraine ends soon, the fundamental shifts it has unleashed in the global economy will play out for years. More pressure on food prices is certain if the harvest in Europe’s breadbasket — a major source of grain and sunflower oil — is disrupted by the war. New Covid-19 lockdowns in China could revive supply chain chaos that helped push up inflation in the first place. Some observers think the Fed has moved too slowly. Others think that its assault on inflation will cause a recession.

So for the country, and for Biden especially, there’s more frustration to come.