One day in March last year, Oleg received a call at work from an official at the Russian culture ministry. The government wanted the theatre director to ask his actors in a remote corner of Siberia to record video statements in support of President Vladimir Putin and his “special military operation” in Ukraine. “No,” Oleg responded, without giving the request a second thought. “We don’t have anyone here who wants to do that.”

The director, who is in his forties, straight-talking and energetic, with long hair pulled back in a bun, had come there from Moscow to this remote corner of Siberia in a bid to turn the local theatre into one of the country’s great cultural institutions. Four years later, Oleg was sure he could speak for his team.

Since the start of the war, he had been in a state of horror and shock. He was glued to his phone, reposting petitions and photos of bombed-out buildings in Ukraine. He’d continued coming to work every day, functioning on autopilot, but the shows he put on night after night increasingly made him sick. The worst were the comedies. Audiences had started piling in to see them, each one playing to a full house. “People weren’t just coming to the theatre, they were coming in droves, as if they were in a state of mass hysteria,” Oleg told me of the first weeks of war. “I’ve never seen audiences laugh like that. It was a kind of frenzy.”

He dragged himself through rehearsals anyway. His assistant and friend ended each run-through with a cry of “Glory to Ukraine!”, assuming that, like Oleg, everyone agreed. (Some names and details in this article have been changed to protect the identities of people involved.)

A few days after the first call, officials reached out again. This time, they threatened to strip the actors of their honorary titles if they didn’t comply. Oleg had seven “merited artists of the Russian Federation” on his staff. He felt he should at least pass on the request. “Guys, have a think. It’s up to you,” he said at a hastily called meeting.

The director knew that his “merited” actors had long prized their status, which confers prestige and a higher salary. He knew, too, that residents of areas far from Russia’s capital tended to be more supportive of the state. But when the actors present responded “Why not?” and told him they would happily record the support videos, Oleg was dumbstruck. The actors didn’t just want to protect their honorary titles, they were earnestly pro-war. “They told me, ‘But the government is doing everything right,’” Oleg recalled. “I understood then that it was all over.”

After the meeting, some of the actors came up to him to express their condolences. They knew Oleg’s politics and pitied him. They could tell that, across the country, a powerful tide was turning against people like him. Over the following months, that tide would crash into Russia’s cultural world, especially the theatre, an institution that holds a near-spiritual status in the national imagination, its actors akin to Hollywood stars.

Dozens of its leading figures would be demonised by pro-war politicians, denounced by colleagues and purged from their jobs. Many would flee the country. Censorship would smother creative life and Russia’s freethinking theatre scene — just months earlier considered one of the greatest in the world just months earlier — would be devastated. Those who chose to stay in the country would struggle to keep working and stay true to their antiwar beliefs. It was a battle of impossible choices, one that many, including Oleg, would eventually lose.

Hours after Russia’s invasion began, the Meyerhold Centre, an experimental venue in the centre of Moscow, became the first theatre to protest. “We can’t not say it,” read a statement posted online. “We can’t not say: No war.”

One after another, actors, directors, ballet dancers and conductors followed suit. Within days, about 2,000 Russian cultural workers had signed an open letter to the government opposing the war. Some went into the streets to protest, including young playwright and festival director Yury Shekhvatov, who was detained by riot police, beaten and spent 15 days in jail. A handful of theatres added peace doves to their logos. Russia’s top Shakespeare scholars issued a joint statement. Legendary St Petersburg director Lev Dodin pleaded with the Kremlin on the pages of industry magazine Teatr: “I beg you, stop!”

The sense of collective resistance did not last long. Less than two weeks into the war, Oleg received a call from a former official with whom he had been on friendly terms. “What the hell are you doing?” she asked. “Don’t you realise they’re already digging a file on you — and very thoroughly?” She warned him to delete his antiwar posts on Facebook. A few days later, representatives of the culture ministry came to meet with Oleg in person for a “disciplinary conversation”.

Such warnings are significant in Russia, since most theatres are formally government institutions. The culture ministry has final say on budgets and hiring and firing staff, a hangover from the Soviet Union. Back then, theatres would have to run scripts by the state censor. If approved, officials could attend rehearsals, editing as they saw fit.

Once the bloc collapsed, those limits were swept away. Oleg could recall no instance of meddling in his work or speech during his career. Though some cases of repression and censorship in the industry did occur as Putin’s regime became more authoritarian, Russian theatre flourished.

The war upended this order almost immediately. Hours after the invasion, Elena Kovalskaya, the Meyerhold Centre’s artistic director, resigned. Four days later, the ministry fired her colleague, director Dmitry Volkostrelov. The new director appointed in his place ordered the theatre’s media team to delete all antiwar statements. The media team quit too. By March 1, a week into the war, the ministry had subsumed the theatre under another institution, meaning that, for many, the Meyerhold Centre was dead in all but name. The last time a theatre bearing the name of early Soviet director Vsevolod Meyerhold was shut down was in 1938, during Josef Stalin’s Great Terror.

In Ukraine, Russian forces were still attempting to seize Kyiv. On March 16, missiles destroyed the theatre in the southern Ukrainian city of Mariupol. On March 17, the renowned Ukrainian actress Oksana Shvets was killed during an air strike. The same day, the Ukrainian national opera’s lead ballet dancer also died from injuries sustained in an earlier strike.

Oleg agonised about what was happening in Ukraine. Developments closer to home shocked him too. In Ulan-Ude, the capital of the Buryatia region in Siberia, officials not only removed Sergey Levitsky, a local theatre director, but also began legal proceedings against him. He was accused of breaking the law by posting antiwar sentiments on social media. “They got him straight away, and over exactly the same thing,” Oleg said, adding he did not want to get fired for the same reason. “Then I’d never find a job in Russia again.”

Levitsky continued to speak out against the war, undeterred by threats, police visits to his home or the fact that a case was soon brought against his defence lawyer as well. “Do not be afraid to speak the truth,” Levitsky wrote on his Facebook page one evening. “Be afraid instead of losing your humanity, be afraid of your conscience, be afraid of becoming unfree inside.” Self-censorship, he argued, was the beginning of the end.

Oleg weighed his options. His daughter had cystic fibrosis, and he had spent the first days of the war scrambling to get her and her mother out of Russia, fearing sanctions might cut off access to crucial medical supplies. Mother and daughter settled in Bulgaria. He had them to consider and support. “This was the main goal,” Oleg recalled. He thought it over for a while longer and then deleted almost everything he’d written against the war.

Zhanna, a dark-haired, dark-eyed young set designer, perched uncomfortably on her chair in a busy café in St Petersburg. Her gaze measured the distance between our table and the others nearby. All of them were within earshot. Should we go for a walk instead, I suggested. She laughed. “Things that once seemed fantastical have now become real,” she said, as we stepped outside. “It’s a dystopia come to life.”

A few weeks into the war, Zhanna found out that proceeds from one of her plays were to be directed to a charity for the Donbas, the Russian-occupied region of eastern Ukraine. Mention of the Donbas had become a byword in Russia for pro-invasion views. Zhanna attempted to protest the decision, but was overruled. On the ground in Ukraine, the war was quickly turning disastrous for the Kremlin. It needed to ramp up support at home, and the cultural ministry used a string of patriotic charity events it called “Open Curtain” — some fundraising for the families of Russian soldiers who died, others offering free seats — to force theatres into publicly taking sides.

One by one, Zhanna’s colleagues and friends chose to leave the country. Almost all of Russia’s star directors left. Kirill Serebrennikov to Berlin. Yury Butusov to Paris. Dmitry Krymov to New York.

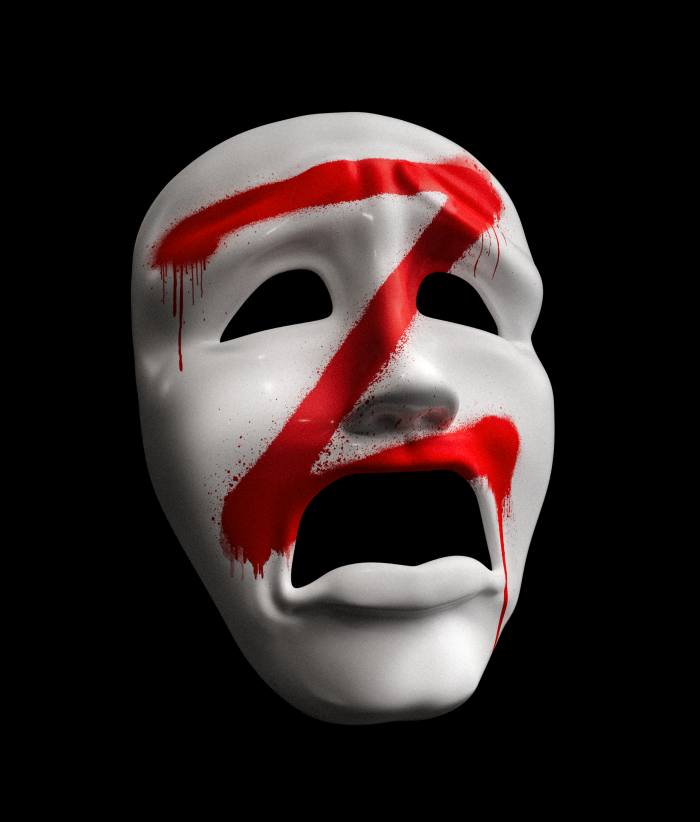

Then came the letter Z. It was first used by the Russian army as an identifying tag on the sides of its tanks invading Ukraine, but swiftly migrated on to T-shirts, billboards and bumper stickers, adopting new meaning: unwavering support for the war. Teachers made children pose for pictures in Z formations. So did the director of a kids’ leukaemia ward.

On March 29, a Moscow theatre stuck a massive version of the letter to its facade, three storeys high. The theatre’s director, Vladimir Mashkov, a longtime Putin supporter, claimed the decoration was his own initiative. Others followed suit, whether by order of the ministry or of their own accord. Within days, dozens of Russian theatre buildings were marked with a Z.

In Moscow, director Nikita Betekhtin began to collate a public Google Doc list of every theatre in the country that had attached the Z to its facade. Betekhtin, who remained a vocal critic of the invasion, called them the zigateatry, meaning “the theatres that had done the Sieg Heil Nazi salute”.

Every morning on his way to work, Oleg wondered if he’d arrive to find the letter installed by officials. “I decided for myself then that if they did hang the Z, I would write my resignation letter the same day.” One April morning, he arrived to find the workers in his carpentry shop had handmade a large Z out of Scotch tape in the theatre courtyard. It hung there on a workshop wall. He wondered what to do. If he ordered them to remove it, he might be denounced. Oleg paced, mulling it over.

Finally, Oleg got the workers together and told them the DIY logo had to go. “Guys, what are you doing?” he asked. At the time, local malls and schools were receiving bomb threats and being evacuated, a fact he decided to use. “You want us to start getting bomb threats too?” The staff agreed to take the letter down without seeing through the ruse. For a time, Oleg waited for blowback, but nothing happened. “I felt like a hero,” he said.

By the summer of 2022, the bodies of Russian soldiers killed in Ukraine were arriving at Oleg’s town. Its Philharmonic orchestra building was turned into a makeshift funeral hall. Coffins were placed on a table and draped with the Russian flag, soldiers lining the stage. Services started early in the morning, Oleg recalled, three or four a day.

Soon, authorities asked some of Oleg’s actors to take part in the memorials by reading eulogies and mournful poems, without consulting him. They agreed. “I couldn’t even look at these people,” Oleg recalled. “I didn’t understand the director of the Philharmonic at all. How she could let those events be held in her venue.”

He couldn’t stay out of it for long, however. Oleg received a letter from local authorities, ordering him to pay the actors for their time working at the funerals from the theatre’s budget. Funding funerals for soldiers killed as a result of the invasion crossed Oleg’s personal red line. “I decided for myself that I wouldn’t pay, no matter what.” Again, he searched for a way out. “This is a military organisation,” he protested to the politicians. “It’s their funerals; let them pay for it.” He stalled for weeks, leaving the matter unresolved.

In the meantime, Oleg had another problem. He’d agreed to host a play at his theatre by a visiting Moscow director who’d spoken out against the war. As banners for the production went up, local newspapers accused Oleg and his theatre of “supporting fascism”. “They said that anyone who bought a ticket was a Nazi, and so on,” Oleg said. And yet, the show went on without further incident.

Still, across Russia, an informal blacklist was being compiled. The Golden Mask, Russia’s Oscars for the theatre, began to remove shows from its annual competition by directors who had left the country or spoken out against the war. It cut so many that it had to cancel the 2022 prizes for best director and playwright. State theatres also purged plays by some antiwar writers and directors. The credits of the ones they kept were edited to remove the offending name, leaving some plays directed by “director”.

Sitting in my Moscow kitchen one evening, Alexander, a theatre actor in his sixties and much beloved in Russia, described life on the blacklist. On tour with a light-hearted comedy, he’d travelled to a smaller Siberian town, ready to play the starring role. When he arrived at the theatre, he discovered that his face had been crossed out on the posters and playbills. They were all marked with the words “actor replaced”. Local police took selfies with the star, before realising they had to detain him.

At Oleg’s theatre, when a lighting designer was hired from another city, authorities banned him from coming. He’d written something antiwar on Facebook in the past. “There is a literal list, and this list is used to check who can and cannot come,” Oleg said. “I have no doubt.”

In August, some members of Russia’s rubber-stamp parliament and other pro-war figures set up a “group for the investigation of anti-Russian activities” in the cultural sphere. Its acronym was Grad, like the missile system being used in Ukraine. Grad began to name people it believed should be purged from their jobs. “We need to pull this scum out with the roots,” one member said in a televised discussion. “They should all be re-educated,” another agreed.

The group zeroed in on a handful of people, including theatre director Alexander Molochnikov. Within days, the Bolshoi Theatre had cancelled Molochnikov’s upcoming premiere, and others quickly followed suit. After receiving threats, the director left for New York. Speaking to me on the phone one day, Molochnikov said that his peers, Russia’s great directors in exile, would be remembered as the stars of this epoch of Russian culture. They were the new Meyerholds, “while the big bastards . . . the Grad officials . . . they don’t stick around”. In the end, he said, “they’re the ones that get erased”.

Betekhtin, the author of the critical Z-theatres list, quickly found all his plays across the country shut down. The Meyerhold Centre, under its new management, also wiped his name from its website. Soon, police officers were coming to his home. Not long after, Betekhtin left Russia for good. “I don’t regret anything,” Betekhtin wrote on Facebook. “A career as a theatre director vs an attempt to frustrate the regime’s plans to make theatres swear allegiance to the Z — the choice was obvious. And between prison and forced emigration, I choose to wander the world.”

The story was repeated in whispers, throughout Russia’s creative world. “It has been an unprecedented purge,” said Zhanna, as we walked circles in snowy St Petersburg. Less in the public eye, she chose to stay in the country. But she revisits that decision every day. “In all this nightmare I feel OK, knowing that my suitcase is [packed and] lying in the wardrobe,” she said. “Everyone feels the same way: I’m here . . . for now.” She used to fear the war, she said. “Now I mostly just fear that my own country may destroy me.”

At the end of summer, as Russia prepared to stage annexation referendums in the four regions of Ukraine its troops occupied, Oleg received a phone call from the FSB, the state security agency. An agent asked him for the personnel files of all theatre employees who had Ukrainian heritage or Ukrainian surnames. They listed a few names of interest.

Oleg could not refuse. But he found a way to warn the individuals in advance. Oleg felt he’d done what he could, but “it was yet another killer final straw”.

On September 21 last year, the Kremlin announced a mass military mobilisation of 300,000 men. Recruitment offices kicked into gear. Conscription notices were given to employers to hand out to their staff. Men scrambled to secure exemptions or get out of the country. Flights out of Russia sold out. Queues of vehicles many kilometres long formed on the country’s land borders. Across Siberia’s theatres, “they grabbed violinists, they grabbed ballet dancers”, Oleg recalled. One of his employees, a stage manager, simply disappeared. “I believe he went into the forest.”

He happened to be visiting another Siberian city that week, meeting with the local theatre director, a colleague and friend. She had just received seven conscription orders for her staff. She went to the authorities, demanding it be cut down to four. They settled on five. Oleg listened to her account of the bartering with disgust. “She was deciding who of her team would be sent to be killed and to kill others.”

Oleg did not receive any notices to hand out — or exemptions. Calling the culture ministry to demand them, he was told: “Exemptions? What exemptions? If they call your people up, they go. Everyone goes.” Oleg decided to leave the country and reunite with his family.

The mobilisation drive continued across Russia for weeks. Alexander, the actor in his sixties, came to work one day to find his theatre’s lobby had been turned into a conscription centre. The same happened to the Roman Viktyuk Theatre in Moscow, leading to protests from the arriving conscripts: the theatre was still draped in a banner advertising its next show, Gogol’s Dead Souls.

At a comedy theatre in a major Russian city, two dozen actors were brought together by their artistic director. “Dear friends,” the director says on a recording of the meeting, which was shared with me. “The department of culture has requested to borrow you to form three concert brigades.”

The brigades would be sent to entertain the troops. “We are a comedy theatre and will be there to create more optimism, joy and happy smiles.” On the recording, actors can be heard beginning to protest. “I remind you, that the [culture ministry] is our superior and we report to them . . . We can’t refuse this,” the director says. “And, in general, I believe this is our duty.”

She gives them homework: prepare repertoires of songs and funny skits. “What happens if someone doesn’t want to go?” one person asks.

“Our boys are there, our people. We need to lift their spirits . . . Do you really not want to go to those places where our boys are suffering?” the theatre’s director says, careful to avoid the words “war” and “front line”, adding that male actors who agree to entertain the troops will receive official exemptions from military service.

“What happens if someone doesn’t want to go and perform?” one of the actors asks again.

“If you decide you don’t want to go,” the director concedes, “you lose your exemption.”

A long silence falls.

“So it turns out no one actually has a choice,” another actor says. “If we refuse to participate, we lose our exemptions and could be grabbed . . . at any moment.”

The artistic director responds: “We’re doing this to help you.”

Last November, people crowded into the Moscow Art Theatre, unravelling scarves and checking fur coats. The theatre, a stone’s throw from the Kremlin, was putting on a premiere of a new play written since the beginning of the war, and the hall was packed. In the story, a theatre is run by a star director who suddenly dies. His replacement, appointed by the culture ministry, comes to the job from the FSB. Brave, I thought. Until the message began to turn. Over the course of the performance, the theatre troupe is increasingly presented as sordid, paedophilic, corrupt. While the FSB graduate-turned-director is cruel, but clean and pure throughout.

Konstantin Bogomolov, the play’s director, sat in the audience. Husband to a woman believed to be Putin’s goddaughter, the 47-year-old’s work was clearly heralding the start of a new era in Russian culture, with new people and new authoritarian values centre stage. The play seemed to welcome it all, along with the disposal of the old order. The uproarious laughter of the audience at jokes about blackface and homophobic slurs was nauseating.

Similar changes were taking place elsewhere. The director of Moscow’s most important museum, the Tretyakov Gallery, was fired by the cultural ministry and replaced by Elena Pronicheva, the daughter of an FSB general, who had a career at state gas company Gazprom. “The vacuum left behind by those who fled the country or were blacklisted will be filled very quickly by those who are more loyal to everything going on,” Zhanna, the St Petersburg set designer, explained. “It’s just a question of how quickly it will happen.”

For Ivan, a director in St Petersburg, the damage feels total. “Russian theatre in recent years was truly the best in the world. We had learnt so much from Europe. We were soaring; it was soaring,” he said, as we met in a quiet café on the outskirts of St Petersburg. “And at the very moment when it was at its peak, it was cut down. It was dealt a fatal blow. We lost everything.”

His theatre company, built over a decade, was blacklisted last year and fell apart. His star actor began taking on construction jobs. Many of the people he respected in the industry, particularly in the capital, are gone. Fear, he said, has “contaminated everything. The worst thing that happens is that self-censorship switches on. It’s really hard to fight it. Because all around you, people are being arrested . . . I hear that voice in my head too.”

Though the balance can skew towards the pro-war patriots in regional cities like Oleg’s, Ivan feels that in almost everyone around him in the industry in St Petersburg — “95 per cent” — is against the war. It’s the minority, the denunciation-writers, the informers, that has taken control of culture. “We’ve gone back 30 to 40 years. The patriotic element, it’s all crawling back to the surface,” Ivan said. “The time of the talentless. It’s their moment.”

A handful of people gathered in a tiny bookshop in the back of a St Petersburg building. A Donetsk People’s Republic flag hung on the wall. A modified Kalashnikov was propped up below it. They were attending a reading by Alexander Pelevin, a feverishly pro-war poet, who has cultivated a following writing poems that are at once lewd and patriotic. “Beg for forgiveness, bitches! So you’re not chopped up like swines!” He was reading in a theatrical tone, a poem addressed to Ukrainians. As he spoke, he squeezed a toy pig that the gathered party had nicknamed Taras, a common Ukrainian name.

Meanwhile, people passed around trophies: Ukrainian schoolbooks they said had been brought from Mariupol, the city pulverised and then occupied by Russia. They joked about acts of violence towards Europeans. Bookshop staff collected donations for Russian soldiers in Ukraine. The group was small, and some of its members were clearly on society’s margins. But they were drinking champagne. Whatever was happening on the front lines, at home battles were being won.

The next day, Liya Akhedzhakova, one of Russia’s greatest living theatre stars who performed for 46 years at Moscow’s Sovremennik Theatre, was stripped of her stage roles. She’d spoken out multiple times against the war. “The director told me that I will no longer be in the repertoire, after some letters from enraged people,” Akhedzhakova told a journalist. “I’m sitting and crying. I understand who’s writing and organising this, but nothing can be done.”

Hours later, Pelevin weighed in on Telegram, celebrating her departure. “When the creative intelligentsia, which hopes for the defeat of the Russian army, is finally driven from the Russian stage, that’s only ever a good thing.” There were more purges to come, he wrote, adding, “The broom will reach everyone.”

It’s something the younger generation of Russian theatre workers anticipates too. Censorship might be far from total yet, but “the rakes will continue, and they will start raking smaller fish in soon”, Ivan said. “Sooner or later, they will get everyone.”

Oleg remained in Bulgaria with his family, debating whether to return. Ukraine was recapturing swaths of territory at the time. Faced with humiliating defeats, Russia’s domestic propaganda was reaching new heights. In late September, Putin brought his elite together in a chandelier-studded hall to announce his annexation of four Ukrainian regions. “Rus-sia! Rus-sia!” the assembled group bellowed. Putin and his officials joined in on stage, holding hands.

Oleg called the culture ministry and told them he would not be returning to his job. He didn’t make it political, saying only, “I have to look after my child.” Then, in a message, he announced his departure to his staff. Kind responses flooded in, bidding him farewell and wishing him luck. “I was sitting there crying. Thinking, wow, how lovely.”

But the next day, the culture ministry suggested he take an unpaid, six-month leave instead. The idea appealed to Oleg since it gave him time to find a decent replacement. He wrote to the staff announcing the reversal of his decision. “That’s when it got brutal,” he said. Some people had an eye on his job; others had been against him since long before. Then, one of the title-holding actors denounced Oleg. In a letter written to the local governor, he stated that Oleg had fled Russia to Bulgaria to escape conscription and that he’d repeatedly said that he was against the war. Within days, Oleg was fired.

Last summer, Anna, a costume designer, and I headed to the Deutsches Theater in Berlin. A few months after the start of Russia’s invasion, the FSB had paid her a visit during play rehearsals, and Anna left the country. She ended up in Germany, a hard-won residence card in hand.

We were en route to see a new play by director Kirill Serebrennikov, one of his first since formally leaving Russia and since the Gogol Centre, his world-famous theatre in Moscow, was shut down. Many of his actors were on stage again. The hall was packed. One actor read long monologues in German — he didn’t speak the language but had learnt the sounds. During the rounds of applause after, I could see Anna was moved almost to tears. Perhaps she too could make a new creative life here.

But over the winter, her funds began running low. She was offered a short theatre project back in Russia. We sat for hours talking over the decision to return. In Ukraine, Russia was shelling power stations, forcing every family to confront the freezing cold. As they suffered, Russia’s patriots cheered.

Oleg has no desire to return. He cannot imagine producing work that does not directly address the war. Some in Russia, he believes, will be able to continue making theatre that opposes the state — subtly, somewhere between the lines, like they did in Soviet times. Sometimes he stalks his old work WhatsApp group and sees his former colleagues posting patriotic memes. One of the theatres he used to work with is now putting on a propaganda play about the war. His own theatre has just held a charity event to support Russian troops. In those moments, he is sure that he was right to leave.

But then he sees acquaintances — people who quit in protest, people who fled — trickling back to Russia after failing to find a place for themselves in the west. “As if nothing is happening there. As if it’s normal . . . This really throws me,” Oleg says. “Because, shit, I left everything behind. I have nothing left.”

In Moscow, audiences have started going to the new Gogol Theatre, which has replaced Serebrennikov’s blacklisted centre. The venue’s last premiere sold out. They also go to the new Meyerhold to watch plays where the director’s name has been erased. “That’s the most horrible thing. It makes you think, then, well, what was all this for? You’re sitting alone in Bulgaria. What for?” Oleg says. “It’s quite frightening to end up nowhere . . . to jump into nothingness.” Then, he gets another reminder. The letter, for example, from the Kremlin addressed to all theatre directors about what was acceptable to stage in honour of last year’s Day of Unity, celebrating Russia’s destruction, occupation and annexation of Ukrainian territory. Then it becomes clear again.

Polina Ivanova is a foreign correspondent for the FT covering Russia, Ukraine and Central Asia

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first