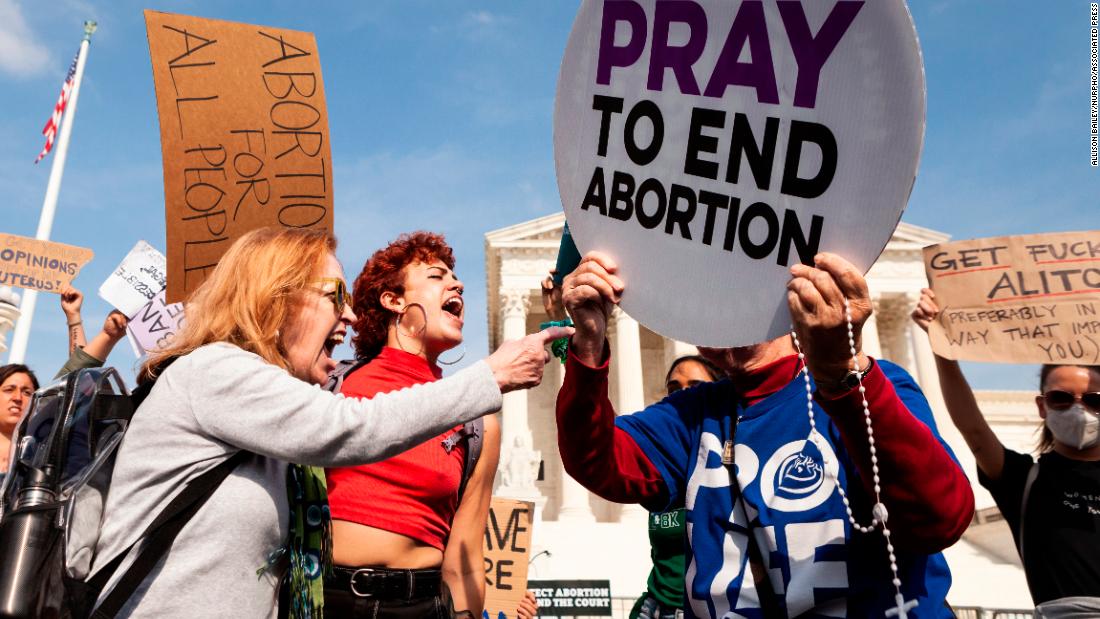

Of course, the implications of this story stretch far beyond Washington, partisan politics and dueling interpretations of the law, the nature of precedent and the Constitution.

Losing access to abortion would mean millions of women would be deprived of the right to make decisions about their own bodies — even if their health or very lives are at risk. The burden for this huge erosion of women’s rights is likely to fall heavily on poorer, minority women who already have worse health outcomes and access.

Yet for all its human dimensions, the issue of abortion is an inherently political question. After all, if the court overturns Roe v. Wade, it would be the culmination of successive Republican political campaigns that produced a conservative majority on the court. And it would further widen the growing cultural, legal and political gulf between Republican-led states, where abortion would likely be banned, and Democratic-run bastions where legislators will likely keep it legal.

The Democratic challenge

The challenge now for Democrats — in the run-up to the midterm elections in November and potentially for years to come — is whether they can build a similarly effective campaign on abortion as Republicans have.

For decades, Republicans up and down the ballot have emphasized calls to abolish abortion and the need to create majorities in Washington to build a Supreme Court hostile to abortion rights.

That difference may reflect the revolutionary zeal of conservatives mobilizing to overturn a status quo and the complacency of liberals who had lived with it for most of their lives.

One anti-abortion activist, Mallory Carroll, who serves as vice president of communications at Susan B. Anthony List, told CNN’s Erin Burnett on Tuesday that the issue always motivated the right more than the left.

“Historically, the intensity gap has favored pro-life candidates,” Carroll said, but she added that she believed the issue would motivate voters from both sides in November.

That same realization pulsated through Massachusetts Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s comments on Tuesday outside the Supreme Court.

“The Republicans have been working toward this day for decades,” Warren said. “They’ve been out there plotting, carefully cultivating these Supreme Court justices so they can have a majority of the bench who would accomplish something that the majority of Americans do not want.”

But for the most part, Republicans worked through valid political structures to reach the Rubicon that the Supreme Court seems about to cross. And Democrats lacked the ruthlessness to match their passion for this single goal.

But the question for Democrats is: can they get people to vote on it?

Former Texas state Sen. Wendy Davis thinks they will, after seeing pro-abortion rights rallies spring up around the country on Tuesday.

But there is no guarantee a singular focus on abortion will mitigate stiff headwinds Democrats are facing on issues like high gasoline prices and inflation.

How Republicans may be vulnerable

On the face of it, Democrats suddenly have one answer to a problem they’ve been facing for weeks: What is their message in a midterm election campaign weighed down by an unpopular President and an apparent inability to answer voter concerns over high inflation, immigration and crime?

In theory, it should be simple for them to knit together the looming abortion ruling with claims that Republicans — some of whom are embracing hardline campaigns against transgender rights and demagoguing discussions of race in education — have raced to radical extremes. A message stressing the need to save abortion rights — or punishing Republicans for overturning them — might also be a way to shore up support among suburban female voters who were critical to Democrats winning the House in 2018 and Biden’s 2020 victory.

“We are going to organize, we are going to rally, and we are going to fight for the rights of our fellow Texans, especially the right to an abortion that is under attack in this state unlike any other place in the country,” O’Rourke said.

Abortion is an issue that will emphasize one of the emerging characteristics of Texas politics — the schism between Republicans, who dominate state power and draw on the state’s vast heartland, and cities like Houston where most Democratic voters live. That’s a divide mirrored across the country.

Democrats who have raised concerns about the intensity of their base enthusiasm also hope to use the issue to skewer Republicans in swing states like Wisconsin. As the Politico story reverberated, Sen. Ron Johnson, who’s the most vulnerable Republican incumbent senator this year, was already trying to shift the conversation back to topics that have put Democrats on the defensive.

“You take a look at open borders, 40-year high inflation, record gas prices, rising crime,” Johnson said. “They can’t talk about the results of their governance, so they’ve got to try and find something else to run on.”

Muted conservative celebrations

Conservatives ought to have been celebrating on Tuesday at the prospect that a longed-for political victory was in reach.

“You need, it seems to me to — excuse the lecture — to concentrate on what the news is today. Not a leaked draft, but the fact that the draft was leaked,” McConnell, now the Senate minority leader, told reporters.

Another member of the Senate Republican leadership, Sen. John Thune of South Dakota, also seemed reticent to weigh in on the impact the Alito draft opinion — and an eventual final Supreme Court decision — could have on the midterms.

“I don’t know it’s necessarily a party issue,” Thune told CNN. “I think it’s more of an issue of conscience.”

Republicans’ caution may reflect concern that the political furor could cause some conservative justices to water down their position and threaten a victory on Roe v. Wade. But it also shows how a campaign shaping up inexorably in the GOP’s favor now suddenly has an unpredictable element.

And Democrats think they have an opening.

“They’re like the dog that caught the bus,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said. “They know they’re on the wrong side of history. They know they’re on the wrong side of where the American people are.”

CNN’s Alex Rogers, Manu Raju, Melanie Zanona, Morgan Rimmer and Ryan Nobles contributed to this story.