After doing a couple of science degrees, Tim Young worked at the BoE, most formatively in market operations, and then as a university lecturer covering finance and monetary economics.

In November, the Treasury made the first of many payments to the Bank of England to cover a public sector loss on quantitative easing. Despite being £828mn, media coverage of the payment was sparse and often dismissive of its significance, including suggestions that the payment represented merely an internal public sector adjustment, and that losses on QE could be left to accumulate as a meaningless BoE liability. These misunderstandings tend to arise because public knowledge of the operational details of QE, and quantitative tightening, its reversal, is weak.

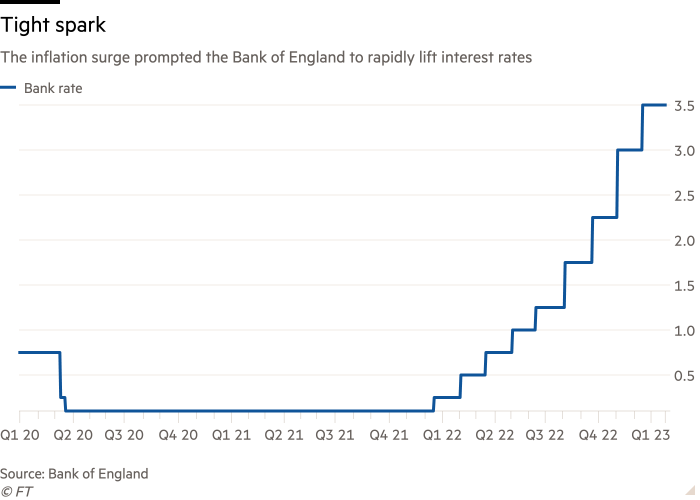

But such losses do matter, and could be compromising monetary policy choices. Understanding the process sheds light on central banks’ apparent reluctance to tighten monetary policy aggressively in response to the recent surge in inflation.

QE is defined in terms of the quantity of reserves — positive balances in commercial banks’ current accounts at the central bank — created when the central bank buys assets paid for in newly created reserves. In the UK, almost 98% of these assets were UK government bonds or gilts, so for brevity, discussion of private sector bond QE purchases is omitted here. Only commercial banks can hold reserves, so if the central bank buys from a non-bank private sector (NBPS) seller, it makes payment by crediting the reserve balance of the seller’s bank, which in turn credits the seller’s bank account to the same amount. Note that this means that, to the extent that the central bank bought bonds held by commercial banks, QE expands deposit money less than reserves.

Reserves generally bear interest at the central bank’s policy rate, in the case of the BoE known as “Bank rate”.

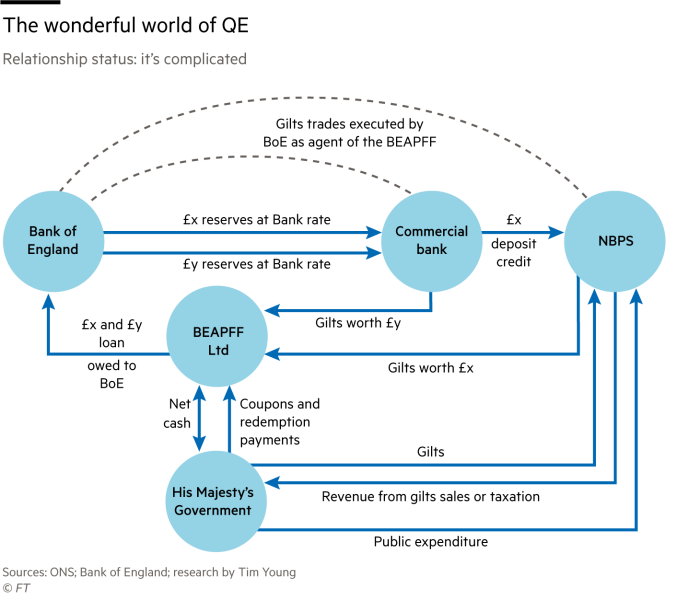

Uniquely in the UK, public confusion has been exacerbated by the fact that QE/QT, while controlled and executed by the BoE, has been done on the books of a special purpose intermediary, the Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Ltd (BEAPFF), a subsidiary of the BoE. In other words, the BoE transacts as an agent of the BEAPFF, with QE/QT counterparties settling their trades with the BEAPFF.

The BEAPFF pays for bonds purchased under QE using a Bank-rate-bearing loan from the BoE, increased in step for each purchase, and the bonds are held by the BEAPFF. By agreement between the BoE and HMT, the beneficial owner of the BEAPFF is HMT. This arrangement insulates the BoE balance sheet from profits and losses made on QE, in the latter case effectively granting the BoE an indemnity. Moreover, since 2012, profits and losses made by QE have largely been remitted to HMT, keeping the BEAPFF equity close to zero. This flow of transactions is depicted in the diagram below. Hereafter, this article discusses BoE QE/QT operations, but my account can be applied to other central banks by consolidating the BEAPFF into the BoE.

As the BoE wanted QE to expand deposit money, the BoE deliberately sought to buy the longer-dated gilts typically held by long-term savings funds.

Various public sector bodies, including HMT and the BEAPFF, have current accounts at the BoE but these balances are not classified as reserves, so payments between either of those and the private sector change the stock of reserves.

Like practically all central banks, the BoE’s beneficial owner is its government, meaning that all the BoE’s liabilities and assets, and any net losses and profits its balance sheet generates, are ultimately owned by the taxpayer. Thus, reserves are effectively public sector debt, so when a gilt holding is purchased under QE, there is initially no effect on the market value of public sector debt. Naturally, QE does effectively switch some of the funding of the public sector debt from fixed-term, fixed-rate gilts to perpetual floating-rate BoE debt, though.

Once the BoE has purchased gilts on behalf of the BEAPFF, and the BEAPFF has taken on a loan of equal value from the BoE to make payment to the private sector counterparty involved, thereby creating reserves, the BEAPFF begins to generate cash through-flow. Cash is drawn into the BEAPFF from gilts coupons and redemption payments. To make these payments, the government procures cash from taxation or borrowing, generally sourced from bank deposits and thereby eliminating reserves and deposit money. Meanwhile, the BEAPFF passes cash out to the BoE in interest due on the loan from the BoE, and in turn the BoE pays the interest on reserves to the banks, recreating reserves, which the banks may pass on to depositors, thereby re-expanding deposit money.

The cashflows due to be paid into the BEAPFF by bonds purchased are fixed over the bonds’ remaining life, including a string of coupon payments and a redemption payment at maturity. The yield-to-maturity represents a blended return of the coupons and the amortised change in value of the bond between purchase and maturity, so provides a guide to the return locked-in at the time of purchase (“guide” because the cashflows generated by the bonds are lumpy). The price paid determines the quantity of reserves created to pay for the holding and the value of the addition to the loan from the BoE to BEAPFF that funds the purchase. Naturally, the Bank rate (of interest) paid on the loan fluctuates according to monetary policy, generating a variable flow from the BEAPFF to the BoE. Thus, in general, the bond and loan interest flows into and out of the BEAPFF will not net out.

Over the BoE’s QE programme, bond purchases (now ceased) have mostly obtained yields above Bank rate, so, until recently, QE has generated net interest income for the public sector. As per the indemnity agreement, HMT has withdrawn the resulting surpluses from the BEAPFF, and used them either for additional expenditure, or to maintain expenditure and reduce the national debt, both of which the public understand to be of real benefit to them. Alternatively, surpluses could have been retained as positive equity in the BEAPFF, presumably to be invested by buying additional sterling securities from the private sector, without increasing the BEAPFF’s loan from the BoE. Either approach would have held the stock of reserves constant (as required unless the BoE adjusts the policy quantity).

Now that interest rates have been raised to stem inflation however, the net interest income has turned negative, so for the foreseeable future, HMT will be paying cash into the BEAPFF to prevent its equity going negative. Because such deficits have to be covered by increased taxation or borrowing, they will constitute an additional burden on the taxpayer.

When a gilt held in the BEAPFF matures, HMT makes a redemption payment into the BEAPFF, plus or minus, under the terms of the indemnity, any mismatch between that payment and the value of the loan additions used to purchase that holding. In the 89% of gilts purchases made at a price above par, this requires HMT to find additional cash. The payment reduces the stock of reserves, and, as the inflow is netted off the BEAPFF’s loan from the BoE, the BoE’s balance sheet contracts. If the BoE wants to maintain the stock of reserves, it has to buy more gilts on behalf of the BEAPFF, and increase the loan again.

However, it had originally been envisaged that when extraordinary monetary policy easing was no longer needed, especially if inflation looked set to rise above its target, central banks would begin to reduce the large stock of money that QE put into circulation. While this is termed QT, the quantity is not so specifically managed as under QE. QT can be done either passively, by ceasing to disburse or reinvest coupon and redemption income, with the BEAPFF instead using the income to pay down some of its loan from the BoE, leaving the stock of reserves and deposit money somewhat reduced. Alternatively, if the central bank wishes to accelerate the process, it can do so by actively selling bonds, which as inflation has recently surged, the BoE is tentatively beginning to do. Again, HMT covers any mismatch between the value realised and the value of the loan to fund the bond’s purchase.

With BEAPFF bond holdings now generating cashflow deficits, it might be supposed that active QT would be a good way for the BoE to tighten monetary policy to tackle rising inflation. What makes active QE awkward for the BoE, however, is that throughout its QE programme and especially during the pandemic, gilts purchases mostly locked in yields around all-time lows, funded at monetary policy rates that, albeit generally lower than the bond yields, were also around their all-time lows, with plenty of upside, if only just towards “normal”. Since monetary policy rates have risen, with bond yields having risen in anticipation of a long period of higher monetary rates, active QT would crystalise embarrassingly large losses.

Given that the average yield on gilts purchased under QE was about 1.5 per cent, including half of the gilts held when QE reached its maximum size of £875bn purchased during the pandemic at an average yield of about 0.5 per cent, compared with a normal Bank rate of, say, at least 2 per cent, and given that the average remaining life of gilts in the BEAPFF is about thirteen years, it seems very likely that, over its lifetime, BoE QE will realise a total loss in the order of £10bns, if not £100bns. Surpluses generated when monetary policy rates were low will almost certainly be exceeded by later deficits.

There is no monetary policy imperative to remove reserves by active QT, provided that the interest rate paid on reserves is always sufficiently rewarding for banks to be content to hold reserves. If a below-market rate of interest is paid on reserves, although banks are collectively stuck with the reserves created by monetary policy, individual banks can be expected to try to offload reserves by buying things, most obviously loan assets, meaning lending, which would be inflationary. However, assuming that Bank rate is set to deliver the BoE’s inflation target, Bank rate should be a roughly fair market rate.

This suggests that, for the BoE, an attractive alternative to active QT might be passive QT, holding the gilts to maturity. Unfortunately, while this might spread QE losses over time (the average remaining life of the gilts in the BEAPFF is over thirteen years, with the longest maturing in 2071) and make the losses less noticeable, this cannot be cannot be relied upon to be better for the taxpayer. Key to understanding why not is the normal working assumption that fixed income markets are efficient, meaning that government bond yields discount the expected (in the statistical sense) path of monetary policy rates. This implies the same expected loss, with the eventual loss as likely to be larger as smaller.

Another idea mooted is that central banks should simply create more reserves to cover any net interest cost on QE, and run negative equity indefinitely, in the belief that central bank liabilities are meaningless because they can always be serviced by creating more of them. In the UK this would require the indemnity to be cancelled, assuming that the BoE would agree to it. The reason why running negative equity does not help is, again, that the interest cost involved can be expected to more or less equal the loss realised by QT, and since the central bank’s beneficial owner is generally their government, it makes no financial difference where the loss is incurred.

The only sure way to decrease the losses on QE is for the central bank to pay less than a fair market rate of interest on reserves. As noted above, this would be inflationary.

Perhaps banks could be paid less than the monetary policy rate on all but a marginal amount of their reserves holdings, and to prevent inflation, be compelled by the authorities to hold at least that quantity of reserves. The trouble with such a scheme, which would be effectively a tax on banks, is that the banks might pass the tax on to their customers, probably constituting, given the type of customers who typically incur bank charges, a regressive tax. Moreover, such a measure is arguably immoral, given that the banks will have mostly involuntarily acquired an arbitrary amount of reserves through settling payments made to their customers. It would damage trust in the central bank, making it more difficult for monetary policy to ever use QE again, and could even undermine the payments system.

With no painless solution to the problems raised by tightening monetary policy after QE, one can imagine that this is a reason why policy makers seem to be dragging their feet over tightening.