Many Canadians whose travel plans were derailed by flight delays or cancellations are turning to the courts rather than waiting for their complaints to be processed by the agency responsible for enforcing compensation rules.

The Canadian Transportation Agency (CTA) — a quasi-judicial tribunal and regulator tasked with settling disputes between airlines and customers — has been dealing with a backlog of air passenger complaints since new regulations came into place in 2019.

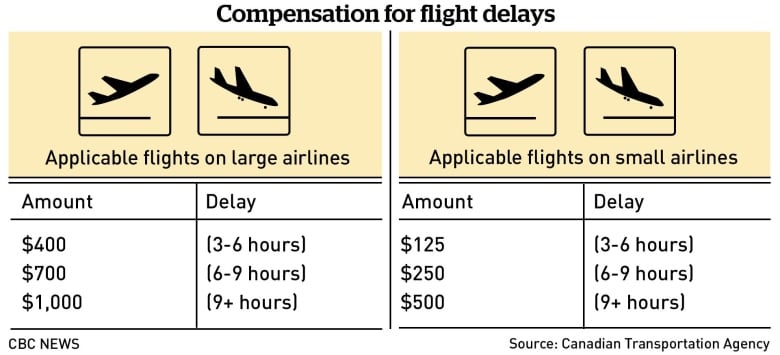

Those regulations require an airline to compensate passengers when a flight is delayed or cancelled for a reason that is within the airline’s control.

That backlog spiked after a hectic summer travel season driven in part by a rise in air travel following the pandemic slump.

CTA officials told a parliamentary committee in November that the agency is attempting to resolve over 30,000 complaints. It added that some complainants could be kept waiting for their cases to be resolved for as long as 18 months.

That’s too long for Kevin Smith of Gatineau, Que., who took matters into his own hands by taking his case to small claims court.

Smith filed a complaint with the CTA in February after a flight from Vancouver to Ottawa on New Year’s Eve was cancelled and rebooked for the next day.

“To wait forever for the government to step in and do something about it when they promised that they would, you feel kind of helpless,” Smith said.

After waiting eight months for the CTA to resolve his case, Smith filed in small claims court in September. Just a few weeks later, the airline notified him that it would settle out of court.

Smith said he was happy that “finally something happened” but is still frustrated that the CTA process didn’t yield timely results.

“What’s the purpose of this whole government agency to even exist if you’re just going to ignore me for what seems like forever?” Smith said.

David Chin of Ottawa had a similar experience — and also decided not to wait for the CTA.

Chin’s flight was delayed for more than three hours in July; he filed a complaint with the CTA in September. Having heard about the agency’s backlog, he decided he wouldn’t wait long.

“I wouldn’t be getting results from them or assistance I need from them,” he said. “So I decided to take the matter into my own hands and go through a different route instead.”

In November, Chin brought his case to small claims court and received an out-of-court settlement days later.

Filing court claim comes with risks: lawyer

Although it yielded faster results than waiting for the CTA, going through the courts wasn’t a simple task either, Chin said. He had to “jump through a lot of hoops,” he said — such as hiring someone to hand-deliver the legal documents to the airline’s legal office in another city, which is required by law.

Sylvie De Bellefeuille, a lawyer with the Quebec-based advocacy group Option consommateurs, said going to small claims court is always a gamble.

“When we go to court we never know for sure what the judgment will be. So there’s a risk. There’s always a risk when we file a complaint,” she said.

De Bellefeuille also said that if an airline decides to challenge a claim in court, it might take years for the case to get through the system.

The CTA says it has taken steps to reduce the backlog by, among other things, “batching” complaints from the same flights to resolve multiple issues at once.

The agency says it’s also conducting a review of its complaint processing system to speed up processing times.

“We anticipate that this ongoing review will continue to yield opportunities for process efficiencies and automation,” a CTA statement said.

When asked what the government could do to help reduce wait times at the CTA, a spokesperson for Transport Minister Omar Alghabra’s office pointed to the $11 million earmarked in the 2022 budget to address the backlog.

“Our priority is to ensure Canadians can travel safely and smoothly and we will continue to work with our partners and key leaders in the air industry,” the spokesperson said in an email.

But De Bellefeuille said passengers will continue to complain unless the regulations are strengthened. She pointed out that the burden of proving an airline hasn’t complied with the regulations is borne by the passenger filing the complaint — but that passenger has to rely on information provided by the airline when a flight is disrupted.

“If it was up to the airline company to prove that [the regulations] were applied correctly, it would be, I believe, a fairer fight,” she said.

The CTA has the ability to fine airlines up to $25,000 if they don’t comply with air passenger protection regulations. But the agency says it has levied only 25 fines since the regulations came into force in 2019.

De Bellefeuille suggested the CTA could levy more fines in an attempt to ensure more compliance.