Paul Gregory began taking daily weather observations in the Annapolis Valley in the 1980s.

Winter weather followed a relatively predictable pattern, he says. A nor’easter would roll in every 10 days or so, dumping 25 centimetres of snow and contributing to a blanket of snow that lasted all winter.

But Gregory, who worked as a forecaster at CFB Greenwood, began noticing a shift in the 1990s.

“I could see the changes,” he says. The cold and snowy winters began to drift away and a warmer, rainier season emerged.

Analysis of average temperatures confirms what Gregory observed. Nova Scotia’s winters are getting warmer, particularly in the last several decades.

It’s a trend that is expected to continue, with a recent provincial climate risk report noting that the province could see just two weeks’ worth of days of snow annually by 2100.

The depth of the snow cover in Nova Scotia is also projected to decline.

While the effects of climate change are multifaceted, researchers say rising temperatures, and the decline in snow, in particular, will have effects on sectors across the province.

Snow declines projected to affect northern tree species

In the Wabanaki/Acadian forest, the decline in snow cover will have consequences for a forest that’s adapted to a certain kind of winter precipitation.

Anthony Taylor, a forest management professor at the University of New Brunswick, has spent a decade studying the effects of climate change on Canada’s eastern forests.

He says snow normally acts as a blanket, insulating the forest floor against the effects of the freeze-thaw cycle, as well as the munching of hungry predators.

This is particularly important for northern tree species, balsam fir for example, that need an optimal temperature for germination. The insulating blanket of snow helps provide those conditions.

“If you have a lack of snow, or no snow, then those seeds tend to be exposed to either too cold or too warm because there’s way more fluctuation in temperature,” he says.

Taylor and his colleagues recently completed research looking at the effects of climate change on snow depth and seed germination going forward. That study suggested germination was negatively affected.

A decline in that insulating snow cover also affects the roots of northern species, which tend to be in the top 30 centimetres of soil and can be damaged by the freeze-thaw cycle.

Taylor says research hasn’t yet been done on whether current rates of seed germination have been affected. But in forestry operations, the effect is already clear, he says.

Taylor, whose family has a forestry business based in Musquodoboit, says the ground is frozen for less time already, reducing the window of time it’s possible to work in the woods in winter. The decline in snow cover also provides less protection for forest soils and new growth against the effects of heavy machinery.

‘Bare soil is always a problem’

The effects of declining snow on soil health aren’t unique to forestry.

While warming winters could, in theory, benefit farmers by lengthening the growing season, the decline in snow cover also means there will be less insulation to protect farm fields from disturbance in the colder months.

“Bare soil is always a problem over the winter,” says Colleen Freake, a small-scale organic vegetable and garlic farmer in Hants County, who is with the group Farmers for Climate Solutions.

Freake says there are ways to mitigate this, including measures she’s tried on her own farm. They include planting cover crops, mulching, and harvesting plants above the growing point, leaving their root systems intact — practices that have the benefit of sequestering carbon.

“Agriculture has the potential to actually sink huge quantities of carbon into the soil,” Freake says.

Meanwhile, Freake says warming temperatures means farmers are already experiencing some increased challenges, such as pests surviving the winter at higher rates.

‘We’re really close to flipping that switch’

In the ocean, these higher winter temperatures have an effect as well.

The Gulf of St. Lawrence is among the southernmost regions for sea ice in the northern hemisphere.

Until relatively recently, researchers thought an ice-free winter was unlikely. But in 2010, DFO scientist Peter Galbraith conducted ice surveys by helicopter and found no ice at all.

“Before 2010, we thought models were predicting that it was going to take a long time before we see no sea ice, and so when it happened, it sort of took us by surprise.”

The following year was ice-free as well, as was 2021 — meaning three of the four times there has been no ice at all since 1969 have been in the last 15 years.

Galbraith says scientists project that ice-free winters will be the norm by 2100, a phenomenon that’s directly linked to rising winter temperatures.

“We’re really close to flipping that switch,” he says.

Galbraith says the effect of other expected changes, like the increase in rain and decrease in snow, are unclear, but the change in sea ice alone will have an effect on the Gulf’s ecology.

“If the winters get too warm, that will eventually threaten snow crab,” says Galbraith.

Ski hills no longer depending on skiing

Back on land, some winter recreation providers are looking to diversify in the face of rising winter temperatures.

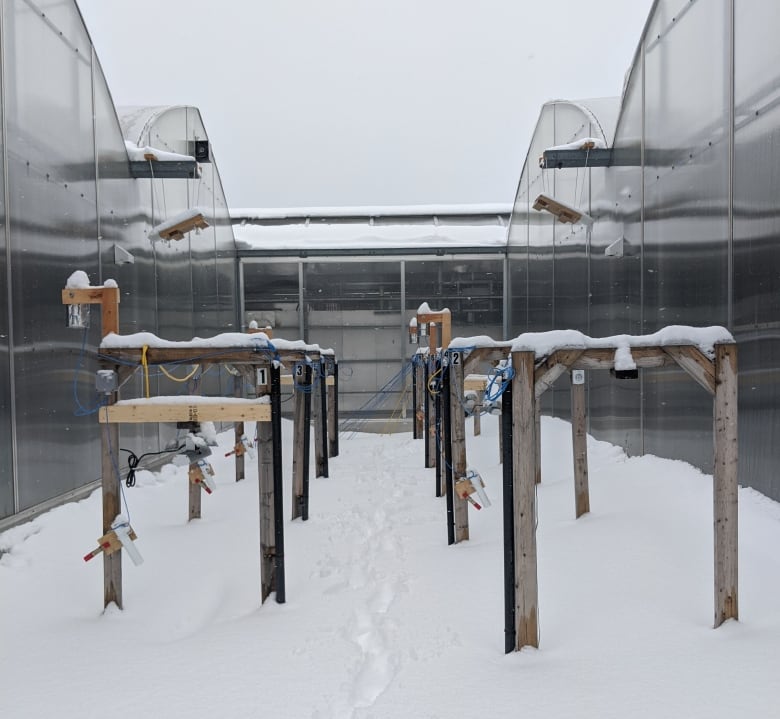

For now, so long as winter temperatures remain cold enough, it’s possible to make up for declines in natural snow with snow-making equipment, says Leslie Wilson, general manager of Ski Wentworth.

Over the years, Ski Wentworth has significantly expanded its snow-making capacity.

“You live and die by snow-making here now, pretty much,” says Wilson, noting that this is true for ski hills across the country.

But looking toward a future in which even hardy manufactured snow can’t withstand warmer temperatures, Wilson says Ski Wentworth is increasing its shoulder-season offerings, such as hiking and mountain bike trails, and plans to move into accommodations.

“That’s an answer to how we’ll deal with the future,” Wilson says. “‘If the season gets shorter in winter, we’ll be open year-round for activities and fun.”