Every night before nine p.m., two lines form outside Vancouver’s Union Gospel Mission. One line is for men staying at the emergency shelter with a reserved bed. The other is for men hoping someone won’t show up so a space becomes free.

“When the beds are full you can’t get in.” explained 74-year old Terry Gilbrook. Gilbrook recently spent two weeks sleeping in Stanley Park because he couldn’t find a shelter space.

“There’s a lot of nights you couldn’t do nothing, couldn’t sleep, so you walked around to stay warm.” he said.

Gilbrook’s experience of being turned away from shelter is happening across British Columbia as facilities struggle to house the most vulnerable in the face of compounding crises: inflation, addiction, and a lack of mental health services. Homes are less affordable at all income levels — increasing demand for the most basic elements of housing: a mat, a blanket, and a roof on winter nights.

“We are looking at individuals who are at a place of desperate struggle and there’s more people who need help than ever before,” said Nicole Mucci, communications manager of Union Gospel Mission.

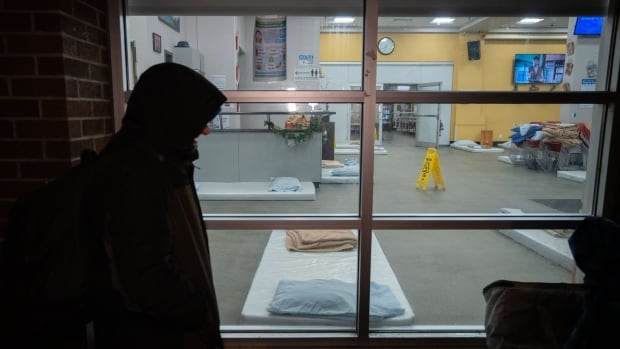

UGM’s emergency shelter has 72 permanent bunk-style beds, and each night staff place 20 mats on the floor of the drop-in centre to house additional men. In the last year, the shelter turned away someone more than 2,000 times, an average of six people a night. That’s a 45 per cent increase in turnaways over the previous year.

When there are no beds available, outreach worker Geoff Dejager phones other shelters in downtown Vancouver, but they are often full too.

“It’s heartbreaking,” he said. “You know someone is vulnerable and you know there is nowhere else they can go.”

It’s hard to keep track of how many people are turned away from shelters across the province, as each facility counts things differently, some have formal waitlists, and the same person may try to access a shelter more than once or reach out to several shelters on the same day.

But calls across the province reveal a network of non-profit organizations regularly at or exceeding capacity.

‘We don’t have enough spaces’

Ruth and Naomi’s Mission in Chilliwack operates a co-ed emergency shelter with an official capacity of 26. Executive Director Scott Gaglardi says it regularly houses 50 people a night, sometimes as many as 60. Mats are placed on the dining room floor, inches apart, with dividers separating areas for men and women.

“It is a very tight squeeze, and it is done simply out of necessity.” He says they had turned people away in the fall when it was warmer, but don’t want to do that now that it’s cold outside.

Gaglardi estimates every night eight to 15 people staying at the shelter are from other cities, either fleeing colder temperatures in the north or more crowding closer to Vancouver.

The Mission Community Services Society in Mission, B.C., operates a shelter with 57 beds, expanding with an additional 12 during extreme weather.

“And still we have turn-aways,” said Executive Director Nate McCready. He estimates the average is roughly three people turned away a night, although some people may be turned away more than once in the same evening.

B.C. Housing, which funds most shelters in the province, admits this is a crisis.

“We don’t have enough spaces. That’s why people are sleeping on the street,” said Sarah Goldvine, B.C. Housing’s vice president of communications and public affairs.

The organization funds more than 4,000 permanent and temporary shelter spaces across the province, with an occupancy rate of 91 per cent. It is investing hundreds of millions of dollars in affordable housing projects, but the supply is not keeping up with demand.

“We see increased need right across what we refer to as the housing spectrum,” said Goldvine.

“And we see that need across the province.”

The affordable housing shortage in British Columbia is fueling a troubling trend: Homeless shelters are so full they regularly have to turn people away, leaving the province’s most vulnerable out in the cold.

When Gilbrook arrived in Vancouver a few months ago, he thought he had enough money to stay in a hotel he’s stayed at before. But it had been sold, and there were no options for the same low price. He’s glad he has a reserved bed at Union Gospel Mission, especially now that the nights are colder.

“Whoever’s got a bed now is going to keep it,” he said. “They’re not gonna lose it, cause it means they’re out on the street so the shelters are going to be pretty well packed, every night.”

And some will inevitably be left in the cold.