The see-through exterior of FIFA’s headquarters in Zurich, Switzerland, was meant to be a symbol of transparency. But with most of its levels below the ground, the home of soccer’s global governing body doesn’t get a lot of sunlight.

Seven years ago, a massive corruption scandal led to the arrests of dozens of FIFA officials and their associates. With the men’s World Cup final set for Doha, Qatar, this Sunday, critics say the organization is still keeping outsiders in the dark about what goes on inside its Swiss bunker.

“Wherever you can’t see inside ostensibly not-for-profit organizations like FIFA, that’s where all the lying, cheating and stealing is taking place,” said Mel Brennan, a former official at CONCACAF, FIFA’s governing body for soccer organizations in North and Central America and the Caribbean.

A decade ago, Brennan worked with investigative journalist Andrew Jennings and others to expose corruption inside CONCACAF. Its general secretary Chuck Blazer later admitted to U.S. investigators that he and other FIFA executive committee members took bribes ahead of various World Cups.

Since then, “FIFA’s become more polished,” Brennan said. “As to whether there’s been actual change, I think they’ve just become slicker.”

At this year’s tournament in Qatar, corruption allegations have been nearly as notable as the on-field action. U.S. prosecutors have accused FIFA officials of taking bribes in exchange for voting for Qatar’s winning bid back in 2010, as well as that of Russia, which hosted the 2018 men’s World Cup.

‘No checks and balances’

FIFA itself says it is ready to move on, touting “extensive reforms” since 2016 under president Gianni Infantino, including an overhaul of its ethics code and changes to how World Cup hosts are selected.

Last year, the U.S. Department of Justice awarded FIFA and other soccer organizations $201 million US ($240 million Cdn) in compensation for their losses as “victims” of various corruption schemes by their own executives and others.

“FIFA has gone from being toxic, almost criminal, to what it should be, a solid and well-respected organization that develops football,” a FIFA spokesperson said in a statement to CBC News.

But Brennan and other long-time observers believe FIFA and its affiliated soccer organizations still need a far greater shake-up before fans can be confident that the sport’s darkest days are behind it, with Canada, the U.S. and Mexico jointly hosting the next men’s World Cup in 2026.

“The kind of reforms that would be helpful, that have to do with transparency and have to do with outside regulation — we haven’t seen any of that,” said Ken Bensinger, a New York Times reporter and author of Red Card: How the U.S. Blew the Whistle on the World’s Biggest Sports Scandal.

The trouble is finding someone who can regulate it. FIFA isn’t a company, nor is it tied to any government. It’s a multi-billion-dollar non-profit — one with more member countries than the United Nations.

And, observers point out, it’s largely unaccountable to anyone other than itself.

“There’s no system of checks and balances in global football,” said journalist Roger Bennett, the co-host of soccer podcasts Men In Blazers and World Corrupt.

“No one understands [FIFA’s] processes. They don’t have to explain them,” said Bennett. “It’s been compared to a drug cartel or the mafia, but it’s neither of those things, because it operates in the bright light of day, with supposed global legitimacy.”

Tracking soccer’s money

At the top level are FIFA’s president and decision-making council, both chosen by its 211 members, who represent national soccer associations.

Each member also has one vote in the selection process for future World Cup hosts. Prior to 2016, that power lay exclusively with the 24 men on FIFA’s now-defunct executive committee. The change was intended to stop hosts from bribing voters, but Bensinger points out it’s not bulletproof.

“In a sense, you’re only just broadening the number of people that need to be bribed. There’s still no outside oversight.”

Since 2016, FIFA has also increased oversight of its multi-billion-dollar revenue and expenses.

The organization makes most of its money selling TV broadcast rights, sponsorship and licensing for its international tournaments, like the World Cup, for which commercial deals brought in a record $7.5 billion US over the past four years. Many long-time sponsors, including McDonald’s, Coca-Cola and Adidas, have stuck with FIFA through its scandals.

The bulk of FIFA’s funds are distributed back out to national and regional soccer organizations around the world. In decades past, with little oversight, millions of those dollars were misappropriated by officials, including Chuck Blazer.

Outside experts say FIFA has made legitimate improvements to monitoring where that money ends up — but it’s hard to keep an eye on 211 different clients.

“Many of the national federations in smaller countries lack basic administrative skills, and before you start with the compliance program, you have to tell them how to make a budget and how to stick to the budget, and all the basics,” said Sylvia Schenk, a sport expert at Transparency International who is currently volunteering as a human rights observer at the World Cup in Qatar.

“That’s a huge challenge and a huge task. FIFA has started to work on it, and the controls have improved, but still there are a lot of problems.”

‘Everyone will applaud us’

When Infantino ran to replace disgraced FIFA president Sepp Blatter in 2016, he did so on a promise to clean up the organization and restore integrity to global soccer.

“We will restore the image of FIFA and the respect of FIFA. And everyone in the world will applaud us,” Infantino said in his election speech.

Infantino is now standing unopposed for a third term, having survived a FIFA ethics investigation, but still facing a criminal investigation in Switzerland over his dealings with the country’s former attorney general. Federal prosecutor Hans Maurer declined to comment on the status of the investigation.

Despite FIFA’s promises of change, the decision to award this year’s World Cup to Qatar remains an emblem of its problems: in the pursuit of money and new soccer markets, it has been willing to overlook human rights, time and again.

So when Infantino implored critics, on the eve of this year’s World Cup, to focus on soccer instead of the many controversies surrounding the tournament in Qatar, many of FIFA’s detractors were unsurprised.

“The Infantino regime will say that they’ve cleared out the old guard, and the rot is gone. But whether you can truly reform an organization like that is a much wider question,” said Miles Coleman, writer and producer of the new Netflix docuseries FIFA Uncovered. “I think we’ll have to see 20 to 30 years down the line if it’s been possible.”

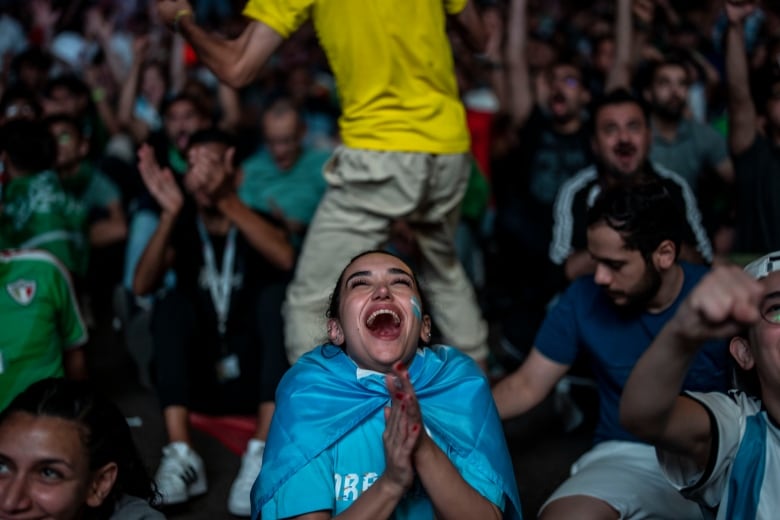

In the meantime, despite grumbling about FIFA’s various scandals, the teams, sponsors and fans seem happy enough to keep coming back for another World Cup every four years.

“The second the ball is kicked, you forget about bureaucracy and processes and human darkness … and you lose yourself in the thrill of football,” Bennett said.

“FIFA knows that if it just keeps playing the hits, it can push through, and just keep on keeping on.”