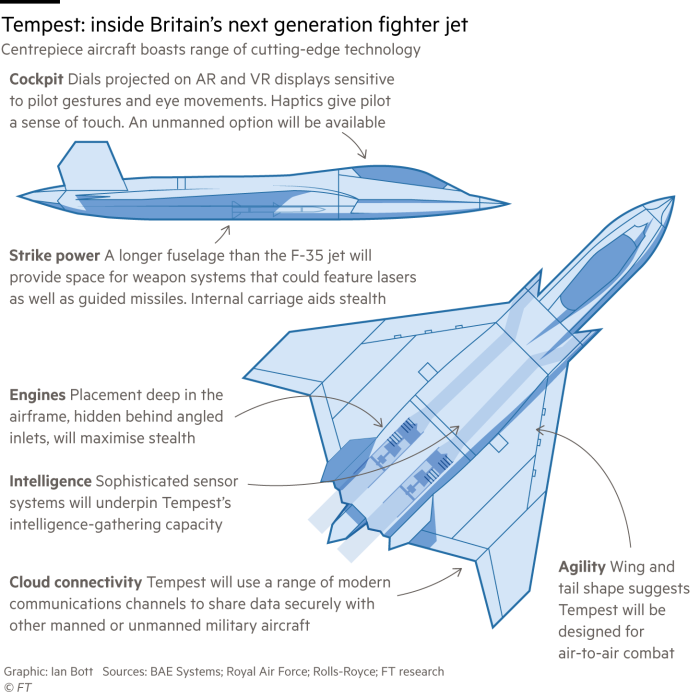

It sounds like something out of a Hollywood movie: a fighter jet set to take to the skies in 2035 equipped with hypersonic weapons capable of travelling at Mach 5, swarming drones controlled by artificial intelligence, and “directed energy” weapons that could use electromagnetic pulses to bring down enemy systems.

The plans are yet to be finalised, but the ambition is unprecedented. The jet would be at the centre of the first ever three-way defence collaboration between the UK, Japan and Italy, built on a design that would put it among the most sophisticated aircraft ever made.

Until now, Japan has worked exclusively with US partners on major military programmes. The tri-national project would merge Japan’s F-X programme with the UK and Italy’s Tempest project, marking a shift in the Asian country’s role in the global defence industry after years in the shadows.

The project would reinforce Tokyo’s determination to forge deeper security ties with a range of allies to prepare for the possibility of a war with China over Taiwan. “[It] will expand Japan’s network to Europe and contribute to strengthening its security environment, while potentially making exports possible,” says Katsutoshi Kawano, the former chief of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces’ Joint Staff.

By working with the UK, he adds, Japan would probably have more flexibility to upgrade its fighter jets to address growing security threats. “It’s unprecedented but I can’t really imagine a case for failure.”

The deal is not yet sealed; over the past few months, attempts to find the perfect moment for a three-way signing have been derailed by the political turmoil in the UK, a change of government in Italy and the assassination of Japan’s longest-serving prime minister.

With fewer than 30 working days left in 2022, the governments of Japan, the UK and Italy are straining to put a date in the diary to formally unveil the partnership or risk budgetary constraints delaying the aircraft’s development until past its anticipated launch date of 2035.

That would set back Japan’s attempts to secure its future in a dangerous and decoupling world confronted by an increasingly assertive China as well as nuclear-armed North Korea and Russia.

The stakes are also high for the UK to make the project work. First unveiled at the Farnborough Airshow in July 2018, Tempest underlines the country’s intention to retain its cutting-edge expertise, despite Brexit, after being left out of a rival Franco-German-Spanish future fighter project. The UK has always made clear it would need international partners, both to help reduce cost and to secure export orders, and signed a statement of intent with Italy in 2019.

If a deal is reached next month, it would be a collaboration between the main contractors Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) of Japan, the UK’s BAE Systems, and Italy’s Leonardo.

Sovereignty is also a key issue for Japan, as it attempts to build defence capabilities to reflect a changing geopolitical landscape.

Behind the effort that has brought Asia’s largest developed country to the negotiating table with the UK is a sense of frustration in Tokyo over the US’s habit of keeping its most cutting-edge technology to itself, say analysts. Defence executives say the move was driven in part by a focus on having onshore capabilities.

“Japan will continue to have a very close relationship with the US,” says Norman Bone, chair and chief executive of Leonardo UK, one of the existing industrial partners on Tempest. “But there are some points where countries have to decide they have to have onshore freedom of action. When they want that onshore freedom of action there are times when the US model is not applicable.”

The Japan-US divergence

For almost all of its postwar history, Japan has been largely dependent on US military technology and troops to defend itself.

But people involved in the discussions say Tokyo’s decision to partner with the UK for its new stealth fighter stems from growing concerns that its local defence industry would not be able to maintain its sovereign capability to develop modern military equipment and weapons without playing a more leading role in their development process.

Japan has long dreamt of building a domestic aircraft to match its famous second world war-era Zero fighter, and officials in Tokyo have pushed for the use of a homegrown design for the replacement for its F-2 fighter jets.

But during the Trump administration, the country came under political pressure to choose a US defence company to jointly develop its F-X fighter even though Tokyo was considering a British alternative to cut its reliance on American weapons.

In late 2020, Japan’s defence ministry chose Lockheed Martin, the US maker of the F-22 and F-35 stealth fighters, as a partner for MHI, which is heading the F-X programme. But it also continued its discussions with BAE Systems, and engine maker Rolls-Royce, according to the ministry. In July, the UK formally announced it would conduct joint concept analysis on future combat air capabilities with Japan and Italy.

While Lockheed remains a partner, people involved in the discussions say talks with the US company stalled over concerns in Tokyo that the aircraft would use US technology designed for the F-22 and F-35.

That would limit the use of Japanese technology, resulting in a “black box” fighter with no access to the source code required for independent upgrades — something the Japanese air force would like and many lawmakers consider essential to sovereignty.

“Japan is seeking flexibility with upgrades to the fighter jet so a black box is not acceptable. We can’t touch the F-35,” says Naohiko Abe, who heads MHI’s defence and space business. “But in terms of whether it makes a difference working with the US or the UK, there isn’t a big difference in terms of development from a corporate perspective.”

Lockheed Martin declined to comment specifically on talks between the governments of the US and Japan but said it had a “longstanding partnership” with Tokyo. The company was “standing ready as the government of Japan considers its F-X partnerships”.

Douglas Barrie, senior fellow for military aerospace at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, says the issue around technology access has long been brewing between the US and its allies.

“From a US perspective it is understandable, you have spent billions of dollars on this stuff and you don’t necessarily want other countries, even your closest allies, to have full access. Conversely if you are a close ally it is obviously frustrating,” he says.

The question of how much control Japan should have in developing the new fighter jet, however, is also an emotional debate that is partially driven by nationalistic sentiment.

The resentment towards the US within some corners of Japan’s defence community stems from its contentious history in developing MHI’s F-2 fighter jets, which are set to retire in the mid-2030s.

In the late 1980s, Japan had initially aimed to develop its own F-2 aircraft but its ambitions for a homegrown design were crushed by pressure from the US during a period of intense bilateral trade tensions. In the end, domestic development of the F-2 was scrapped and its design was based on the US F-16 fighter jet.

Some on the US side believe negotiations over the F-X were fraught with emotions for the Japanese. “It is difficult to overstate how much bravado and national feeling is tied up in this fighter discussion,” says a former senior officer in the US Navy.

A person working for a US company directly involved in the discussions says the nationalistic tendency at times appeared to override the main objective of the fighter jet programme.

“Sometimes it appeared that people were forgetting the reason why they were making this fighter jet in the first place and the mindset was missing that they needed equipment that was necessary to address a stronger China. It just became a question of who was making the aircraft and who the partner should be,” the person says.

‘A relationship of equals’

Japanese lawmakers, industry experts and executives say a closer partnership with the UK makes sense both strategically and financially. In December, the two countries are also set to sign a major defence pact that will make joint exercises and logistics co-operation easier.

“The UK and Japan have similar defence budgets, similar requirements in the same timeframe as the UK and, like us, they need to be interoperable with the US,” says Charles Woodburn, chief executive of BAE Systems.

Japan began considering the UK as a potential partner for its new fighter jet around seven years ago, and talks accelerated in late 2017 during a meeting in London between the foreign and defence ministers of the countries, according to two people with direct knowledge of the discussions.

“I’ve consistently argued that we need a relationship of equals,” says Itsunori Onodera, who was Japan’s defence minister in 2017, adding that his country had repeatedly checked with the UK whether they would be willing to share technology as partners.

“If they can do that, we can make more aircraft and bring down the cost while there could potentially be bigger volumes if the UK can export to Nato countries,” he says.

The UK has a “very strong history of collaborations in defence”, says one European industry executive familiar with the talks, pointing to the Eurofighter programme, which was built by BAE Systems, Airbus and Leonardo. “We don’t want to partner with countries that are not up to the mark on this,” the executive adds. “We don’t want any passengers.”

One initial hurdle was the different size of the aircraft the UK and Japan had in mind, but they began working together on several studies in sensitive areas such as on engines, radar and propulsion technology, all of which will feed into the future combat air system programme.

Rolls-Royce, the aero-engine maker which is developing the engines for Tempest, announced last year it would work with Japan’s IHI Corp to develop an engine demonstrator, while Leonardo and Mitsubishi Electric have been collaborating on a number of joint studies for several years.

Progress has been made at the technical level, according to people familiar with the situation, although issues surrounding intellectual property and export controls still need to be resolved.

Leonardo UK’s Bone says there was a “natural alignment” between the UK and Japan’s air force since both countries were trying to “achieve similar things with similar worries and similar threats”.

According to Barrie of the IISS, another reason driving the partnership between the UK and Japan is likely to be the development by China of a stealth combat jet.

“For the first time possibly ever, the kind of threat platform that the two countries are baselining their needs on is a Chinese aircraft — the Chengdu J-20,” he says. “[It is] one of the threat drivers for the UK and Japan in terms of what kind of combat aircraft they might need in the future.”

Flying business

The UK, Japan and Italy have now entered the final phase of discussions, focusing both on how the costs will be shared and also to what extent the F-X and Tempest can be integrated, according to people familiar with the talks.

Two of those people say negotiators have yet to reach an agreement on how the costs will be distributed between the countries. Japan plans to boost its defence budget by roughly 11 per cent to more than ¥6tn ($42bn) for the year to March 2024, including a request for ¥143.2bn to develop the new fighter. Meanwhile, the British government has said it would commit an initial £2bn towards the project.

But both countries are under pressure to reduce the development costs and are seeking a greater contribution from Italy. Although Rome recently increased its financial commitments to the programme, the country may struggle given the significant budget demands, according to Trevor Taylor, professorial research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute.

“As Japan’s role grows within the programme, it will be crucial to delineate a role for Italy that aligns with its aspirations but matches its resources,” he wrote in a recent note.

A full business case for the Tempest F-X will need to be presented to partner governments in 2025, at which point they will need to commit.

Bringing Japan on board as a fully fledged partner would not only help increase “affordability and scale,” said Taylor in the recent note, it would also potentially open up the Indo-Pacific market as a further avenue for export sales.

It still remains unclear how much the Tempest and F-X programmes can be merged. Japan is considering using digital engineering technology for the F-X. Such a method could save costs as well as making it easier for the Tempest and the F-X to have a common architecture but distinct features, according to Simon Chelton, a former UK defence attaché in Japan and an associate fellow of the Royal United Services Institute.

Japan’s defence ministry declined to comment on details, saying it was going to decide on the broader framework of the collaboration with the UK and Italy by year-end. The UK Ministry of Defence reiterated that work on the “joint concept analysis” was ongoing with Japan and Italy. Further decisions were “expected to be made by the end of 2022”, it added.

While the UK has a history of sharing technology with its partners, industry executives have also questioned whether it can actually provide full disclosure to Japan considering that Tokyo does not have a security vetting system that is comparable to the US and the UK.

Since the fighter jet will need to be interoperable with the US, some people involved in the discussions have pointed to the possibility that Washington may intervene if the UK were to share sensitive technology with Japan.

Leonardo’s Bone stressed that “security processes will get harmonised to an appropriate level” before any formal partnership is agreed, while Japan’s MoD said there was a bilateral intelligence sharing agreement with the UK.

Time, however, is running short if the countries are to meet their ambition to have a jet in service by 2035. The rival Franco-German-Spanish project, the Future Combat Air System, has been struggling to achieve lift-off but is close to reaching the next critical phase.

Industry executives say the Tempest F-X project needs to work not only for the nations involved, but for the US as well. Washington, which needs its allies to bolster their defence capability to counter China’s military rise, has welcomed the UK’s recent focus on the Indo-Pacific region.

“The US side is obviously looking at this [joint Japan-UK-Italy programme] very carefully, and, because of the changing global situation and threats, there may be more US comfort with it than there would have been in the past,” says Lance Gatling, a veteran defence consultant at Nexial Research.

“At this stage, the US may not stand too much in the way of its allies getting stronger, even if it means letting these projects happen. I think the US side also knows that, in the end, it will somehow be involved.”