Steinfeld didn’t set out to share her own experience in the film. The project began as a way for her to connect survivors to empower them not to suffer in silence alone, like she had done.

Arriving in the US, Steinfeld says she was severely traumatized and unable to speak about her experience, trying instead to start a new life. But it wasn’t as simple as just moving away from the scene of the crime.

That’s what sparked the idea for Steinfeld’s’ project. But as she interviewed the people featured in the film — including a wife raped by her husband, a nurse who had to use a rape kit on herself, a man who says he was raped at a party when he was 13 — and confronted some of the perpetrators about whether they now felt remorse or even admitted what they had done had been a crime, she realized that in order to fully heal, she too had to speak out in order to move on.

Following her experience, Steinfeld shared four lessons she has learned on what to do in the wake of an assault — whether it happened to you, or someone you know.

It’s not your fault

“No matter how it happened, no matter your gender, sex, age, creed, no matter your state of consciousness, no matter what your actions or lack of actions were, IT IS NOT YOUR FAULT,” she says.

“You are obsessing now with the question: what could have been done differently? The truth is not much. Perpetrators prey on you by earning your trust and coercing you to a space where they can commit the crime. You couldn’t have known their intentions. The faster you learn to understand it wasn’t your fault, the better you’ll heal.”

Find a person you trust

“Find a person you trust — someone you know who won’t judge you or force you to do anything you would not like to do — if possible BEFORE you seek medical attention and report the crime to authorities,” Steinfeld says.

She adds that experiences with law and medical personnel can also be traumatizing so it’s helpful to have trusted support when reporting the crime.

“Make sure you confide in someone who will be by your side no matter what. That might mean telling your family what happened and seeking their love and support. Don’t worry now about crushing their heart with your disclosure of the crime you managed to survive. They may feel helpless, but you need them right now more than I can put in words. If you don’t have such a person, find us, victims’ advocates, we will be there for you. I know it’s a slogan, but it’s so true — find us online! YOU’RE NOT ALONE.”

Have patience with yourself

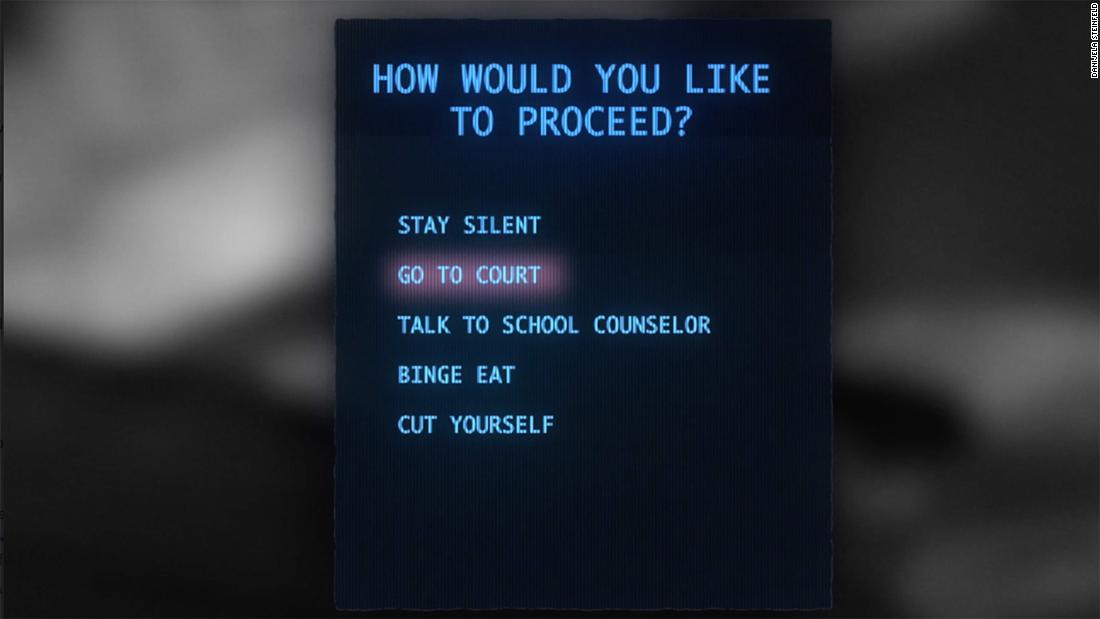

“You might feel self-destructive: you might hate yourself for a long time, you might want to harm yourself, abuse alcohol or substances to make yourself feel more miserable. Have patience with your state of shock and your healing,” she says.

“The journey from victim to victor could be a very long way to go. Victory is when you are whole again, when you can trust your judgment again, victory is when what has happened has no power over you anymore. The fast track to that freedom is patience and kindness towards yourself.”

She explains that by doing this you will eventually be able to talk about what has happened and says she learned that “speaking was healing for all the heroes that came forward after surviving sexual trauma.”

Ask loved ones to be supportive

When abuse survivors share what has happened to them, it might be difficult for loved ones to know how to respond, Steinfeld says. But their response “can be crucial” in helping people feel empowered to seek support.

“We live in a culture that doesn’t understand survivors of sexual violence. There is no right or wrong way to respond to trauma,” she says, concluding that having validation and support can go a long way in helping someone feel safe and ask for support.

Story of the week

Several years ago a group of women became trailblazers in the commercial fishing industry, believing their lives were set on a more prosperous course. But climate change along the Zambezi River threatens to put an end to their dreams.

Women Behaving Badly: Junko Tabei (1939 – 2016)

Written by Adie Vanessa Offiong

Although she was the first woman to reach the peak of Mount Everest, Junko Tabei preferred to be known as the 36th person to achieve this feat.

She discovered her passion for climbing at the age of 10 during a class trip to Mount Nasu and Mount Chausu. At the time, in Japan, only men climbed mountains. After graduating from Showa Women’s University, Tabei followed her passion to climb and joined various men’s climbing clubs.

To encourage more women to pursue passions for climbing, she co-founded Joshi-Tohan (Ladies Climbing Club of Japan) in 1969 and, the following year, Tabei and club member Hiroko Hirakawa made history on an expedition to Annapurna III in Nepal, one of the most challenging climbs in the world, becoming the first women to scale the peak.

Tabei then set her sights on Everest. In 1975, along with 14 other women under the auspices of Japanese Women’s Everest Expedition, she began the ascent. Due to lack of oxygen bottles, Tabei was the only member of the climbing team who could climb the final summit, making her the first woman to reach the top of the world’s highest peak.

She went on to climb the highest mountains on each continent, known as the Seven Summits challenge, and was again the first woman to do so.

Born in Fukushima as Junko Ishibashi, Tabei was a teacher, author and World War II survivor. She married Masanobu Tabei, a fellow mountaineer, in 1959.

Her life was one of courage and determination not only making a name in a male-dominated field but also challenging cultural stereotypes about women. She died from cancer in 2016.