It took Shafiullah Sadat almost 10 months to reach Belgium from his native Afghanistan, which he fled fearing Taliban persecution. His fate since lodging his application for asylum six weeks ago has been to join the swelling ranks of thousands of homeless migrants in Brussels.

“Everywhere I go there are people sleeping on the streets,” says the 27-year-old, who has been living rough near the so-called Petit-Château, an imposing building housing the federal authority in charge of refugee reception. “I never imagined it would be so hard here.”

The number of asylum applications is growing across Europe. As of August, applications in the EU, plus Norway, Switzerland, Iceland and Liechtenstein, were up 58 per cent this year compared with the same period in 2021, to 578,875, according to the bloc’s asylum agency.

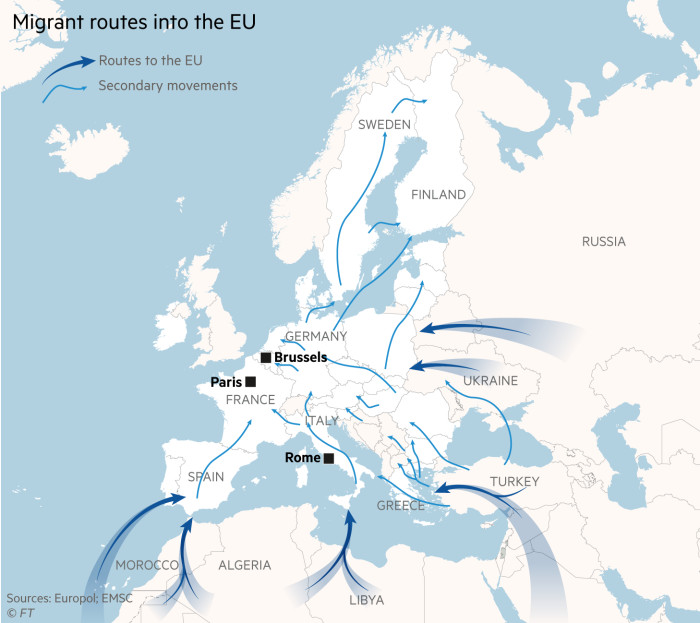

The surge, which is thought partly to reflect the easing of Covid-era travel restrictions, comes on top of the arrival of millions of Ukrainian refugees, whose applications for protection are dealt with under a separate system. When those fleeing Russia’s invasion are counted, the number seeking protection in Germany alone is 1.1mn, just short of the total that arrived during the 2015-16 Syrian refugee crisis.

The influx is stoking fears of a repeat of the divisions between EU member states six years ago over burden-sharing and asylum policy and is placing strains on cities across the region seeking to house the new arrivals.

Tents and sleeping bags have become a common sight along the canal in central Brussels, as well as in underpasses and railway stations, as some asylum seekers are forced to wait months for shelter after lodging applications.

“The reception system is completely overwhelmed,” said David Vogel of the health charity Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Belgium.

Poor health conditions, including outbreaks of scabies and diphtheria, have prompted MSF to take the unprecedented step of setting up an emergency clinic on the street outside the government building in central Brussels that processes asylum applications.

Standing outside the clinic earlier this month, Vogel described the medical situation as “dire”.

In Germany, towns are rushing to set up shelters and convert gyms and hostels. Helmut Dedy, head of the Deutsche Städtetag, the Association of German Cities and Towns, sounded the alarm this month about the rising numbers. “The absorption capacity in many cities is exhausted,” he said. Municipalities were running out of school places and “integration courses” for adult refugees.

Berlin says its shelters are all full to bursting, with 1,600 asylum-seekers and 1,200 Ukrainian refugees still waiting for places to stay. It is planning to pitch tents, each capable of housing 400 people, in the city’s former Tegel and Tempelhof airports.

Lioba Hebauer, spokeswoman for the Federal Migration and Refugees Agency, or BAMF, linked the rising numbers to political and economic pressures in a range of host countries as well as the “catch-up effects” of Covid-related restrictions being lifted.

The bleak reception many are encountering contrasts with the EU’s handling of the influx of Ukrainian refugees earlier this year.

While member states were praised for their rapid response to the millions who fled Vladimir Putin’s invasion, tensions over migration have begun to spill over at an EU level again.

Italy’s new rightwing prime minister Giorgia Meloni, who refused to let a ship carrying 231 migrants rescued from the Mediterranean dock at an Italian port, has depicted unchecked irregular migration from Africa and Asia as a threat to her country.

She has complained it is unfair for Italy to bear the burden of accommodating and processing the asylum seekers, when for many of the new arrivals, the country is simply a gateway to the rest of Europe. The European Commission on Monday outlined a plan to reduce “irregular and unsafe migration” ahead of a meeting of home affairs ministers on Friday.

Meanwhile, the Belgian government is subject to two rulings from the European Court of Human Rights over its failure to provide accommodation to asylum seekers.

“We will do everything in our power to fulfil our international obligations to operationalise emergency shelter as soon as possible to offer protection to those in need, but given the high influx of refugees we have to admit we are hitting our operational limits,” said a spokesperson for Nicole de Moor, Belgian secretary of state for asylum and migration.

Belgium was dealing with “exceptional circumstances”, the spokesperson added, including a shortage of personnel to staff the housing centres for asylum applicants, a lack of suitable accommodation, and a reluctance among local authorities to open centres, given the need to house 60,000 Ukrainian refugees.

Fedasil, the government agency for asylum seekers, said the country was trying to bolster capacity, including by opening two temporary reception centres to house 500 people each. The Brussels region plans to add 1,200 emergency reception places inside its network of homeless shelters, it said.

However, Voyaach Helpdesk, a pro-bono legal aid initiative involving leading law firms, estimates there are at least 4,000 asylum seekers in Belgium waiting for a shelter.

Cécile Ghymers, a lawyer with law firm DNH Legal, who represents young asylum seekers, said that given the paucity of accommodation available, even children — traditionally given top priority — were sleeping rough.

Registered asylum seekers have a legal right to accommodation no matter what their age, she said, but “it’s dramatic and dangerous for children to be on the street”.

One morning earlier this month, Belgian police dispersed scores of people who had slept outside the immigration centre in an unsuccessful bid to start their claims for international protection. Within minutes they were beginning to queue up again as they prepared for another overnight wait.

“You can feel the stress,” said Nathan Torrini, director at Serve the City, a charity that offers breakfast to asylum seekers. “The government showed with the Ukrainian refugees that there’s a better way than this.”

Additional reporting from Amy Kazmin in Rome