There was no sugar coating the horrible economic forecasts in the Autumn Statement. With a historically large drop in UK household incomes, falling real wages and a sizeable recession — all compounded by a new squeeze on public services and higher taxes — Jeremy Hunt had little good news to highlight.

Although the chancellor skated over the worst predictions for Britain’s economy, he revealed just how much he was boxed in by the need to impose the biggest budgetary squeeze since 2010.

But Hunt was willing to accept horrible economic and public finance forecasts, in contrast with Kwasi Kwarteng, his predecessor, who ignored the Office for Budget Responsibility, the fiscal watchdog, and was crucified by financial markets.

The miserable outlook stems from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine pushing up wholesale energy prices to eight times above normal levels. This squeezes real incomes of households by 7.1 per cent by 2023-24 and also undermines the financial performance of companies and the government. There is little surprise that the economy has been pushed into a recession that will last through to the end of next year.

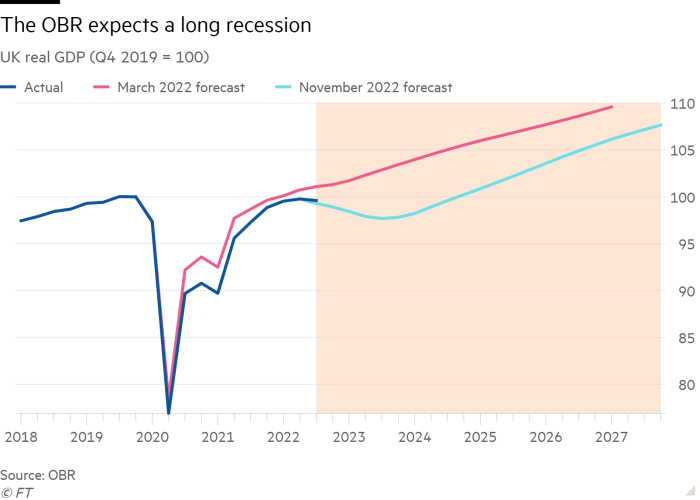

The subsequent recovery is forecast to be notably lacklustre, but here the global situation is less to blame than the UK’s domestic weakness.

In five years’ time the OBR expects the economy to be 3.7 per cent smaller than it thought likely as recently as March — a huge downgrade in economic performance. This means the economy will not have grown at all between the last election in 2019 and the next one, if is called at the end of 2024.

The persistently feeble economy coupled with much higher costs of government borrowing due to high inflation has blown apart the UK’s public finances. In the forecasts Hunt was presented with ahead of the Autumn Statement, the underlying government deficit was revised higher from £31.6bn to £106.4bn in 2026-27 on the back of higher predicted costs of servicing government debt, higher welfare spending due to persistent inflation and weaker tax receipts.

The OBR also told Hunt he was not on track to meet any of the government’s existing fiscal rules. Even when he loosened them — to make them easier to hit by measuring debt and deficits in 2027-28 rather than 2025-26 — the watchdog still reckoned the public finances were not sustainable. Public debt would still be rising as a share of gross domestic product in the forecasts, even by 2027-28, and public borrowing was more than 3 per cent of GDP.

Inevitably, that meant a budgetary consolidation was needed. Hunt bit the bullet and imposed £55bn of spending cuts and tax rises in his Autumn Statement, with cuts to day-to-day spending on public services and capital investment, and tax increases.

The timing of the measures differ. Spending cuts, which rise to £30bn a year, are delayed until the recession is forecast to be over. For the next year, the government is set to support the economy with its energy price guarantee and some funding for schools and hospitals.

Tax rises are coming earlier, however, with £7bn of revenue raising measures coming as soon as April, and then rising steadily to raise £25bn a year by 2027-28.

The tax increases are mostly being imposed through stealth measures that freeze tax allowances and thresholds, ensuring that as incomes, spending and profits rise, a greater slice of them will be taxed or subject to higher rates of tax.

Even as Hunt announced the largest budgetary squeeze since 2010, the OBR said he had not been as prudent as former chancellors in building resilience into the public finances.

“This chancellor has left himself comparatively little headroom against his proposed new fiscal targets relative to previous chancellors,” it said in its report.

The government is hoping that natural gas prices will fall and the Bank of England will not have to raise interest rates as much as the OBR has pencilled in to its forecasts. If that happens the outlook will be considerably brighter and some of the tax increases and public spending cuts might prove unnecessary.

But this may well prove to be wishful thinking. The Autumn Statement revealed that the UK’s economic performance is likely to be far — and persistently — worse than forecasts published in March.

Downgrades of this scale are very rare and, it turns out, extremely unpleasant for any chancellor — and for the nation.