Italian artist Paolo Canevari opens the door of his villa, a russet cube perched on a very green hill. We’re in Amelia, Umbria, an ancient town surrounded by abundant countryside once occupied by the Romans. Rolling hills of wheat, olive trees and tightly rolled hay bales dot the land around Canevari’s home. A nearby convent and pilgrimage trails linked to the one-time presence of Saint Francis of Assisi mark this as one of Italy’s most spiritual areas.

Canevari’s religion, however, is beauty, and a tour of his 19th-century home, purchased in 1980 by his parents (his father, uncle and grandfather were prominent Roman artists), makes this faith abundantly clear. The house was once owned by the aristocratic Morelli and Diaz families and was built on the town’s rural fringes to provide an escape from Rome. When Canevari’s father, the late sculptor Angelo Canevari, saw the house, he “fell in love with it,” says Canevari, transforming the pile into a studio and retreat for the family, while retaining the characteristics of its 19th-century bones and the cotto-brick floors typical of rustic farmhouses. Canevari now lives here with his partner, the designer, author and clinical hypnotherapist Betony Vernon, as well as his mother and sister, who use it as a weekend retreat. Every family member occupies a discrete area of the house, and all seem to co-exist happily.

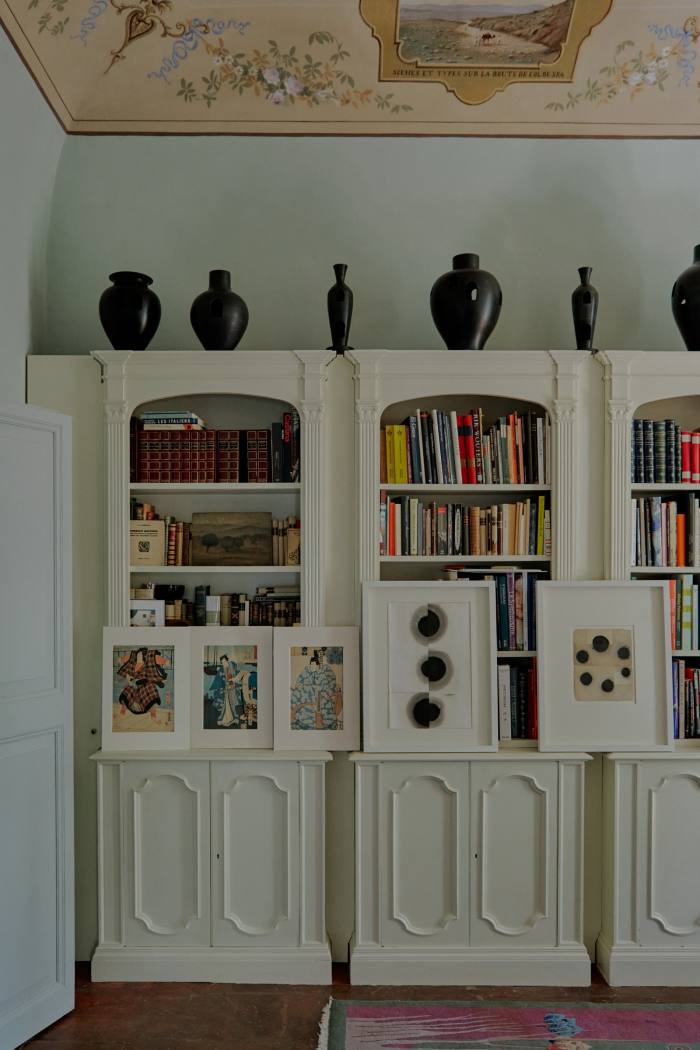

We are in a tightly curated space as much as a home. Each view, each object, each detail: from door handles to teacups, from carpets to desks, to vases and bedcovers, has been selected and installed, or purpose-designed. The main floor upon entering hosts a country kitchen complete with an open fireplace lined with terracotta pots and copper pans, alongside a massive marble sink and other country decor, although a sense of sparsity and spaciousness is maintained throughout the house. Life is staged here, and people are the actors in an utterly quiet and beautiful counterpoint between design objects and artworks assembled by Canevari and his ancestors, along with the few necessary appliances that hoist the house from set into home. “I’m not a collector. I’m an artist,” he says of the ensemble. “An artist can be a designer, a film director, a fashion designer but not vice-versa.”

Canevari is probably best known for his hulking black tyre-rubber sculptures, some depicting images drawn from Roman mythology and architecture, as well as his black furniture shaped like the Roman lupa (she-wolf) or the ebony-coloured chairs riffing on the Colosseum that surprise in their proximity to the work of Adolf Loos or Scottish arts and crafts. These blackest of black furniture pieces match the terracotta vases that Canevari dips in motor oil, or the Malevich-like black squares he creates by soaking ancient etchings and newspapers in oil and then framing the subsequent paintings in period gold frames.

Canevari spent years in New York City and Amsterdam, where he lived with performance artist Marina Abramović, his companion and wife for nearly 14 years. Their interiors were always “spare and simple with furniture from the ’50s and ’60s”, Canevari remembers, acknowledging his predilection for bringing home “finds”, his tastes not entirely shared by his companion. “She grew up in a military environment in a communist country. She understood the value of a house as power, but not in terms of individual objects,” he says of Abramović’s sensibility. He recalls their move to the US with brutal honesty. “I pushed Marina to move there because our careers were there, and so we did, in 2002. Her family had been bombed in Belgrade, so she wasn’t exactly big on America.”

The artist says his passion for found objects “began as a child” – his knowledge and interest deepened over decades by assiduous visits to Roman flea markets and museums. Influences from former lives in Holland and the US also somehow figure behind this Umbrian domestic installation; Canevari’s own living quarters on the first floor include an artist’s studio room, three formal sitting rooms, a boudoir for his partner Vernon and a bedroom consisting of furniture from the 1920s by French designer Louis Majorelle. “I love the way Majorelle transitions from art nouveau to art deco,” Canevari says as he leads the way around a corner to show me an earlier piece, a delicate writing desk inlaid with ginkgo leaves.

Each room has been carefully painted in delicate pastels which Canevari selected with Vernon, a volcanic and captivating presence. She arrives at the end of our visit, sweeping down the pavement in a black silk toga, flourishing a cigarette in jewel-studded hands. Red hair and a pale face belie a gentle and purposeful soul, whose determination to bring talk of sexual pleasure of all sorts into the mainstream marks her out as a leading sexologist, not to mention designer of the erotic jewellery that she has had made for more than 20 years. Her craftsmen, she reveals, are based nearby and she relishes the interaction. The day we meet, Vernon is wearing a double set of gold pleasure balls, her “iconic piece”.

Canevari, meanwhile, is absorbed with the process in which nature becomes sublimated and abstracted, and his house is filled with objects from French art nouveau and 20th-century Italy. Coloured glass vases are bound in iron tendrils, while images of plants curl around terracotta vases. Pinnacles in the collection are a desk and chair by Carlo Bugatti, lamps by Tiffany Studios and furniture by Osvaldo Borsani, Gino Maggioni and, of course, Majorelle. “It was always a question of wanting things I knew, and then searching for them,” he says, pointing to a blue Tongue chair by the French designer Pierre Paulin, gifted to him by some friends. It’s positioned in front of a floral-patterned Japanese screen.

Canevari’s artist studio contains a series of works that take their form from from 14th-century Italian and European paintings and gold-ground panels. Instead of showing hieratic virgins or saints, though, they are completely covered by hand in gold leaf.

Though he creates modern-day icons that reference religious themes, when Canevari hangs a figure of Christ inside a tractor tyre, pivots a rubber military tank on the ground, or covers an ogival panel in gold, it is actually artists ranging from Jannis Kounellis to Pino Pascali and Yves Klein that he is thinking of as much as Benozzo Gozzoli and Caravaggio. Canevari also teaches art at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, and he admits his debt to artistic forefathers freely. Kounellis, and the Italian art historian and curator Germano Celant, in particular, seem to have changed the artist’s life.

Other people of significance in his life are present in the house. A white quartz work by Abramović is prominent in a living room. Works by Nam June Paik, whom he assisted when he lived in New York, also hang with those of Kounellis on the walls. But home life with Vernon has brought out another side to the artist. The Umbrian vision of a New York-harking Roman artist, with an American-English erotic jewellery designer who bounces between collaborations with Valentino, Alexander Wang and the like, seems just right. In characteristic form, one of Canevari’s first works after meeting Vernon was a large rubber inner tube, happily tied up with cords, in the manner of Christo, Piero Manzoni – and bondage expert Vernon herself.

Canevari does not shy away from looking at an ugly world, and in his quest to create a harmonious life somehow squares the fact that his own grandfather undertook artistic commissions for the Fascist regime in Italy, with the compassionate understanding that the idealising statues in the Foro Italico were meant to represent a better world.

The idea that objects have the ability to conjure up culture and time resides in every room in his curated pantheon. Even the garden seems choreographed, and a stroll through the simple park reveals the beauty of each plant upon which the artist has bestowed care, appearing amid trees that have grown here since the house was built. Bamboo, once fashionable as an emblem of exoticism, lines the walkway to the house, while oak, plantain and cyprus trees shade a central garden area, which would have provided summer amusement for the 19th-century villa owners.

Frescoes and other decorative elements inside the house allude to the plants in the garden, intertwined with depictions of the military conquests of former owners, including a fresco of Libya in one room which celebrates the military theatre of its famous inhabitant Armando Diaz, one of the greatest Italian generals of all time. And so a home once again mirrors its owner, and in the hands of Paolo Canevari, Betony Vernon and Canevari’s family, this country idyll is both respite and refuge; a cosmopolitan and deeply learned vision of living informed by creativity.