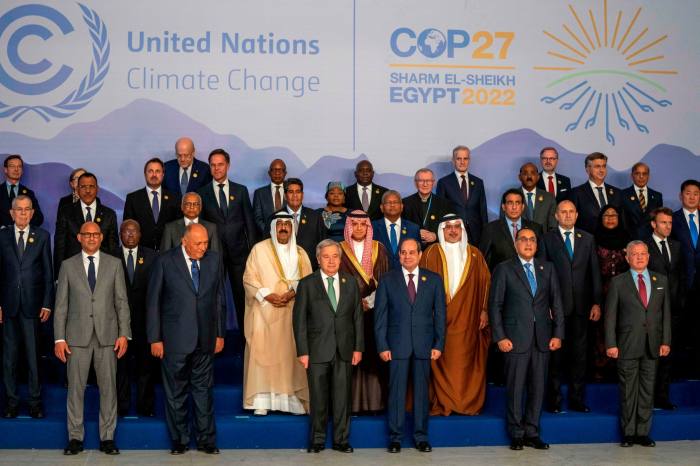

If Egypt’s president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi assumed he could use the COP27 to strut the global stage and project a varnished version of his leadership to his domestic audience, he has been proven wrong. Instead, the ugliest elements of the autocrat’s rule have been thrust into the spotlight as world leaders wrangle over climate change in Sharm el-Sheikh.

By default, the UN meeting has given rare space for Egyptian civil society to voice to the world its anger over the appalling human rights record of Sisi’s regime. COP27 delegates should listen to activists’ anguished tale and use the moment to pressure Sisi.

There is much at stake. Even as Sisi has schmoozed with presidents and prime ministers, the clock has been ticking on the life of one of the country’s most prominent political prisoners, Alaa Abdel Fattah. The activist, who has spent eight of the past 10 years behind bars, had been on a partial hunger strike for more than 200 days.

He stopped drinking water when COP27 opened, triggering serious concerns about how long he could survive. His most recent “crime” was spreading “false news that undermines national security” on a social media post. His conviction in December earned him another five years in prison. Abdel Fattah said in a letter to his mother on Tuesday he had suspended his hunger strike and would give more detail during her monthly visit on Thursday.

He is but one of thousands of political prisoners detained since Sisi’s 2013 coup. Amnesty International said Cairo had arrested 1,500 people since April, including hundreds in the two weeks leading up to COP27 in connection with calls for protests during the summit. Make no mistake, Sisi presides over one of the most oppressive regimes in a region replete with autocrats.

Weeks after Sisi’s putsch toppled Islamist Mohamed Morsi, the country’s first democratically elected president, security forces killed at least 800 Muslim Brotherhood members and supporters in a crackdown at the Rabaa al-Adawiya mosque. Thousands more people with links to the brotherhood were imprisoned as Sisi branded the Islamist movement a terror group. His regime went on to crush all forms of dissent, banning protests and detaining secular activists, bloggers, lawyers, businessmen and journalists. Television stations and newspapers have been taken over by entities affiliated to the security forces and muzzled.

Yet Sisi has throughout enjoyed healthy relations with western governments. They have been happy to welcome the president to their capitals and sell Egypt arms. Despite its economic woes, Egypt was one of the top five importers of weapons between 2017 and 2021, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Western diplomats talk of the need for “quiet diplomacy” when dealing with the regime, and of the strategic importance of a traditional partner and the Arab world’s most populous nation. That should not absolve them from using their diplomatic and economic leverage to pressure Sisi. Indeed, the regime has released about 800 political prisoners this year, even as it arrested others, in a sign that it was concerned about its reputation ahead of COP27.

Yet Sisi has stubbornly refused to release Abdel Fattah, who was granted UK citizenship last year, and many more have been arrested this year. In a letter to Abdel Fattah’s sister on the eve of COP27, UK prime minister Rishi Sunak, who attended the summit last week, said his government was “totally committed” to resolving the activist’s case. US President Joe Biden, who also attended, promised to put human rights at the top of his foreign policy agenda. It is time to deliver on those promises.