Photos of German Chancellor Olaf Scholz shaking hands with Senegalese President Macky Sall this spring offer a stark contrast to the scenes witnessed this week at the COP27 climate conference.

In May, Scholz toured African countries including Senegal, Niger and South Africa, looking for partners willing to drill for natural gas for export to try to counter a European energy crisis sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It’s a proposal that Sall’s government is moving on.

Now, Germany is making headlines for joining up with other nations to help fund the $8.5-billion move away from coal in South Africa. Meanwhile, Sall has been an outspoken advocate at the conference in Egypt, demanding western leaders come forward with more funding for climate adaptation.

Developing nations have successfully added compensation for past climate damage to the COP27 negotiations, following news that keeping global warming to 1.5 degrees is now very unlikely.

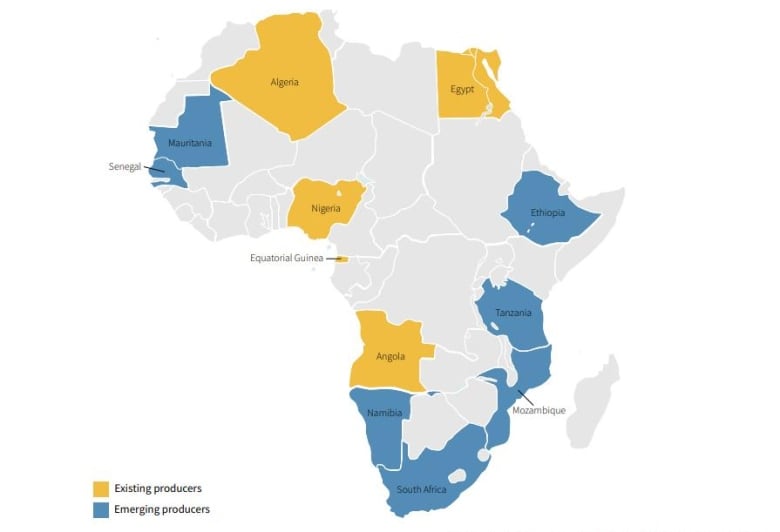

Natural gas reserves have been discovered in a number of countries across the African continent and leaders have been faced with the question of if they should try to capitalize on the recent spike in demand — an issue that’s gotten a lot of attention at COP27.

Sall was pressed on this seeming contradiction at the conference and has said that resource development will allow for greater economic prosperity in his country.

“Let’s be clear, we are in favour of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. But we Africans cannot accept that our vital interests are being ignored,” he said Tuesday.

Those who advocate for the continued expansion of natural gas resources have tagged it as a “transition fuel,” since it has a lower emissions impact than oil or coal. But climate advocates say this is greenwashing and a ploy that will keep African nations stuck in the same development traps of the past.

“This has been justified by saying it will bring development to Africa,” said Lorraine Chiponda, co-lead of the advocacy group Don’t Gas Africa.

“And again, as we all know, Africa has been disproportionately affected by climate disasters. We have contributed very little towards greenhouse gas emissions and we are suffering the most.”

Africa has been disproportionately affected by climate disasters. We have contributed very little towards greenhouse gas emissions and we are suffering the most.”– Lorraine Chiponda, co-lead of advocacy group Don’t Gas Africa

Climate negotiations have always been overlaid with debates about what is a “fair” way to have developing nations move forward.

These countries are not responsible for the emissions that have led to the climate crisis, but are now being asked to limit their emissions in a way Western countries never have.

That’s why Sall and many others argue that African leaders are on solid moral ground in choosing economic development opportunities for their countries.

Those who oppose such development frequently cite four core reasons why African nations shouldn’t invest in natural gas.

Warming disproportionately affects Africa

The scale of natural gas infrastructure expansion completely undermines any hope of hitting climate targets, and missing those targets will disproportionately harm Africans.

“Limiting warming to 1.5 C means that total gas use has to go down,” said Bill Hare, senior scientist with Climate Action Tracker, an independent analysis organization that tracks progress of climate action.

“But the problem is that the pipeline of under construction, approved and proposed LNG facilities is massive. [Natural gas production] should be declining by 2030 but is in fact set to increase by well over 200 per cent over recent levels by then.”

The price of global warming is high and African nations don’t have to look far to see its effects, as the Horn of Africa is currently suffering through a historic drought that is threatening 22 million people with starvation.

Demand and prices won’t stay high

This year’s price surge in natural gas markets that makes these investments so desirable is likely a fickle one, according to multiple analyses.

Hare explains that this so-called dash for gas by European nations has in fact overreached, and will likely result in a glut as supplies increase by about five times the amount exported by Russia before the war.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) said in the latest annual World Energy Outlook that the “extraordinary turbulence” in energy markets is the greatest when it comes to natural gas.

Models used by the IEA project that demand for natural gas will plateau this decade because of the global move away from fossil fuels.

Bad investment strategy

When looking at any potential investment, a government will look at the period of time it takes to earn back the money it cost to build the project.

But as countries move away from nonrenewable energy sources, there is increasing risk that the payback on fossil fuel investments will never happen and infrastructure could become underused or obsolete before the end of its economic life, a concept called stranded assets.

Should prices fall and demand plateau, it is possible these investments will never pay off, especially since it will still take a number of years before they’re up and running.

Reuters has reported that Senegal’s proposed natural gas project isn’t slated to be up and running until 2024 or 2025, and is estimated to cost $5 billion US. A Nigerian pipeline project is estimated to cost twice that.

The African Climate Foundation has raised the concern that these investments won’t pay off.

The risk is substantial enough that many commercial and investment banks have stopped financing new gas projects — including the U.K.’s biggest domestic bank, Lloyds, and the European Investment Bank.

Repetition of historic injustices

On top of economic or climate reasons for not making the move toward gas, Chiponda, with Don’t Gas Africa, also notes that doing so would allow historic injustices to repeat themselves.

“When we see countries from Europe coming to Africa to exploit gas in order to solve a short-term crisis that is in Europe, it shows that their agenda for gas is a neo-colonial agenda,” she said Monday.

“It is an exploitative political agenda that is meant to continue to extract resources from African people.”

Researchers from Nigeria’s Adekunle Ajasin University looked at the history of oil investments made in African countries throughout the 19th Century.

Though they found that oil exporting countries experienced economic benefits of resource development, they also found increased instances of conflict, uneven revenue redistribution and significant environmental pollution.

Signals that these projects aren’t in the best interest of the African people are already starting to pop up.

The IEA has flagged that the current energy crisis is creating the biggest transfer of wealth from consumers to producers ever seen in the natural gas market.

Increased costs are, for the first time in a decade, causing access to modern electricity systems to decline, with 75 million people worldwide standing to lose access, according to the IEA’s analysis.

Meanwhile, the European countries eager to get drills in the ground are also currently snatching natural gas away from developing nations to avoid blackouts at home this winter, according to energy analysts.

At the COP27 conference this week, when asked about the prospect of expanded natural gas capacity in Africa, climate campaigner and former U.S. vice-president Al Gore urged African leaders not to buy in.

“We must see the so-called dash for gas for what it really is: a dash down a bridge to nowhere, leaving the countries of the world facing climate chaos and billions in stranded assets.”