The past two years of American life have been tumultuous by any country’s standards. More than a million deaths in a mismanaged pandemic, a homegrown attack on the seat of government, a legislative decision that targeted millions of women and inflation soaring to a 40-year high, all while the former president looms on the sidelines.

These sorts of things usually upend politics, at minimum delivering a firm rebuke of the incumbent, and in some cases producing a complete realignment. Take the UK’s decision to leave the EU: within three years of the referendum, fully 40 per cent of British voters had switched parties, no longer feeling at home in their old tribe.

But the US appears immune to such shifts. In an election that promised, variously, a red wave of inflation-induced anger, a blue backlash over abortion rights and a Trumpian revival among Republican ranks, the most stunning takeaway is not how much has changed, but how little.

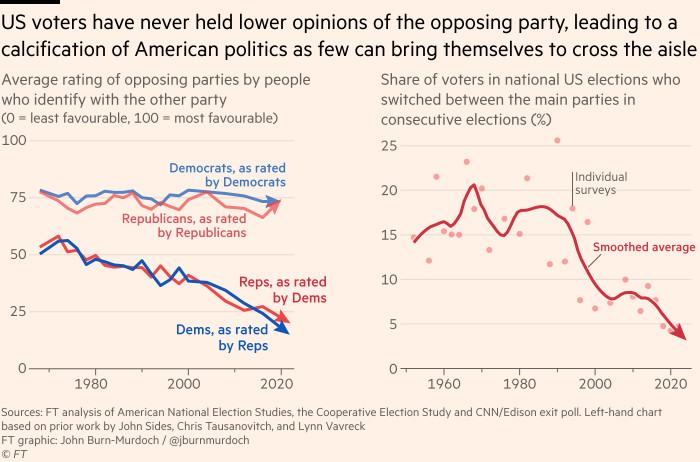

At the time of writing, less than five per cent of midterm voters have changed allegiance since 2020. This is the second lowest amount of vote-switching recorded in a US election since data collection began in 1952, narrowly beaten by the general election two years ago.

Usually such political tumbleweed would imply apathy, but this uniquely American inertia is instead the result of voters feeling more strongly about politics than ever before. This renders crossing the aisle unthinkable for all but a tiny minority.

In the early 1970s, when asked to rate their feelings towards their political opponents from 0 (icy dislike) to 100 (positively glowing), Republicans and Democrats alike placed their rivals at just above 57. Hardly a warm embrace, but cordial enough. Since then, and especially in the past two decades, that has fallen to a frosty 20. Simultaneously, the share of Americans who say there are big differences between the parties has doubled from 40 per cent to 80. Essentially, US politics is calcifying.

We see this stubborn polarisation playing out with specific issues, too. The repeal of Roe vs Wade was unquestionably a huge motivating factor in vote choice this week, best illustrated in Michigan where 14 per cent of former Trump voters backed a bill that creates a constitutional right to abortion. But in the same state’s race for governor, where the Democratic candidate put abortion rights front and centre of her campaign, only half that number swung from red to blue. This suggests party allegiance comes first, even on such a key issue.

How can something that millions are incensed about not have played a bigger role? Because the rise in partisan polarisation over recent decades has come hand in hand with increased sorting on issues. In 1980, attitudes to abortion were virtually indistinguishable among Democrat and Republican voters. But by 2020, Americans were already much more neatly sorted into pro-choice Democrats and anti-choice Republicans.

It is this increasing attitudinal closeness within each party’s base, and the growing distance between the two, that produces stalemates like we saw this week, and there are no signs that the pace or direction of travel are set to change. Indeed, data also shows ideology increasingly trumping identity, as black, Hispanic and Asian voters in the US sort themselves into liberals and conservatives.

One such shift was illustrated by Ron DeSantis’s success in the Florida governor’s race, where the possible Republican presidential candidate won historically blue Miami-Dade county by 11 points on his way to statewide victory. This was a 40-point swing in the six years since Hillary Clinton won the county by 30 points in her 2016 tilt at the White House.

If a week is a long time in politics, then two years is an aeon. But the US political landscape seems almost perfectly calibrated to keep results on a knife-edge. With the parties fighting over an ever-shrinking number of genuinely persuadable voters while the ranks of die-hards continue to swell, my prediction is that we’ll still be waiting up for the result long after polls close in 2024.