Throughout the 20th century, many Indigenous people enlisted in military service to fight wars, risk their lives and make monumental sacrifices on Canada’s behalf. But during those years, the country wasn’t so kind to the peoples who had been here long before Canada’s borders were even drawn.

So why did Indigenous people — especially First Nations living under the control of the Indian Act — choose to fight?

It’s a question John Moses, a member of the Delaware and Upper Mohawk bands from Six Nations of the Grand River, and a Canadian Armed Forces veteran, has been reflecting on for many years.

Moses comes from a long line of military veterans — members of his family served in the First World War, the Second World War and other operations since. He has also co-authored a book on the history of Indigenous people in the military.

The reasons Indigenous people fought “varied according to the conflict and it varied from Indian reserve community to Indian reserve,” Moses told Rosanna Deerchild, host of CBC Radio’s Unreserved.

For example, “there were those who volunteered to serve for the perceived material benefits of regular food and clothing and payment.”

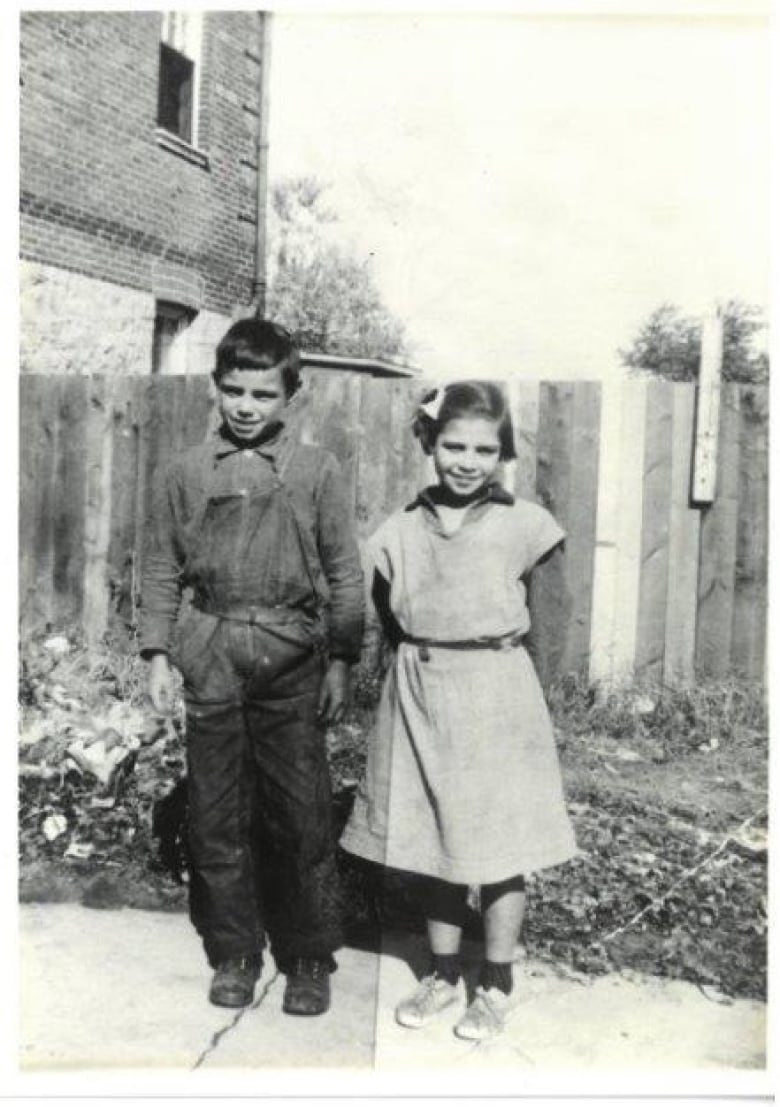

But for Moses’s father, Russ Moses, joining up also served as a kind of escape. The elder Moses was a survivor of the Mohawk Institute Residential School in Brantford, Ont., also known as the “Mush Hole.”

“He had been at the Mush Hole under exceptionally severe wartime and post-war conditions from 1942 until 1947 … marked by severe discipline, malnutrition, overwork and a lack of proper clothing,” Moses said.

“By the time he left the residential school, I think in many ways, both figuratively and literally, he wanted to put as much distance as he could between himself and the Six Nations community and the Mush Hole. And his way up and out of that circumstance was to join the Royal Canadian Navy.”

The clothing was better, the food was better and the discipline was less severe than in residential school, Moses explained. Enlisting was also an opportunity for Russ Moses, who served during the Korean War, to see the world.

“In a sense, I think he wanted to replace old memories with new memories, even if that included going to war.”

‘Second-class citizens’

According to A Commemorative History of Aboriginal People in the Canadian Military, which John Moses co-authored, First Nations peoples were not forced to enlist. Those who served in the First and Second World Wars did so voluntarily.

Veterans Affairs Canada states that more than 4,000 Indigenous people served during the First World War. By the end of the Second World War in 1945, at least 3,000 First Nations people had served in uniform, along with an unknown number of Inuit and Métis people. (Based on self-identification figures taken from the Department of National Defence, approximately 2,700 Indigenous people served in the Canadian Armed Forces in 2019.)

Moses wants Canadians to understand that Indigenous people didn’t sign up for military service because they were deferential toward the monarchy.

“In no situation did Indigenous peoples render service out of, you know, this quaint, naive sense of subservience to the British Crown,” he said. “The issue of whether to serve, and how, is hugely divisive [in Indigenous communities].”

If they had mixed feelings about fighting for Canada, those feelings were only exacerbated when they got back. Upon returning from war, Russ Moses and other Indigenous veterans were treated like “second-class citizens,” Moses said.

“[My father] was denied entry into a bar in Hagersville, which is a small town outside the Six Nations … he was in naval uniform and denied service,” he said. “They knew he was from the reserve and said, ‘We’re sorry, but we can’t serve you here.'”

Indigenous soldiers weren’t afforded the same rights and benefits after their service — such as access to housing and financial and health supports — as non-Indigenous veterans.

First Nations people were still treated as “wards” or “minors” of the state; it wasn’t until 1960 that they were enfranchised and able to vote in Canada.

Nation-to-nation relationship

Anishinaabe sniper Francis Pegahmagabow, from Wasauksing First Nation near Parry Sound, Ont., remains the most highly decorated soldier in Canadian military history after fighting in (and surviving) the First World War.

There were many reasons why he enlisted, but in the eyes of author and poet Armand Garnet Ruffo, one motivation was Pegahmagabow’s respect for the nation-to-nation relationship between First Nations and the Crown.

Ruffo is Ojibway from Chapleau, in northern Ontario, and a professor at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont. In 2018, he was enlisted for a different kind of service: writing a libretto about Pegahmagabow’s life before, during and after the war for a musical production called Sounding Thunder: The Song of Francis Pegahmagabow.

Ruffo had to learn about Pegahmagabow’s life, but also about Indigenous rights during that time and the bigger historical moment of the First World War.

“Indigenous people were doing their part just as [the Crown] had to do its part to support those treaties and honour them,” Ruffo said.

Brian McInnes, Pegahmagabow’s great-grandson, said he believes his ancestor fought in the war because he felt the need to stand alongside the Allied countries, which included Great Britain, France, the United States and, of course, Canada.

“To stand strong and to stand brave and to defend that greater good from harm, because it’s fragile,” he explained. “I think that’s a responsibility that he, like so many other Indigenous peoples of that age and before — and fortunately after — have continued to think about and honour.”

‘It’s important to honour the people’

McInnes is an educator and a scholar and his book Sounding Thunder: The Stories of Francis Pegahmagabow was an important resource for Ruffo in his writing.

McInnes believes that, with whatever threat the First World War presented to people living within Canadian borders, his great-grandfather wanted to defend and preserve his homelands.

“When it comes down to it … these are still lands that Indigenous peoples feel a love and connection to, regardless of what nation-state perhaps claims it politically,” he said.

While McInnes and Ruffo are remembering Pegahmagabow’s life through writing, Indigenous communities across Canada are finding other ways to commemorate their war veterans.

Donald Maracle is the chief of Tyendinaga Mohawk Council, which is part of the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte. With funding from the Last Post Fund — an organization that ensures dignified funerals and burials on behalf of Veterans Affairs Canada — Maracle’s community embarked on a project to finally etch in stone the names of soldiers whose graves had been unmarked for decades.

“Some of them did it for adventure,” Maracle acknowledged. But he said they also fought because they valued peace.

“You know, if Germany had got control, especially during the Second World War with Hitler, and taken over as a dictator of the world, where would the dust settle? I’m sure that was first and foremost in their minds.”

The project to mark the graves of Indigenous soldiers in Tyendinaga is one effort among many that are needed to show proper respect to Indigenous veterans. “There’s a lot of catching up to do,” Maracle said.

“It’s important to honour the people … who gave their lives for the freedom and peace that people oftentimes in this country take for granted,” he said. “It was purchased at a very high cost of human life.”