As It Happens10:17This political prisoner will stop drinking water when world leaders gather in Egypt

WARNING: This story contains distressing details.

Sanaa Seif is scheduled to visit her brother in prison in a week and a half. But she fears that by then, it will already be too late.

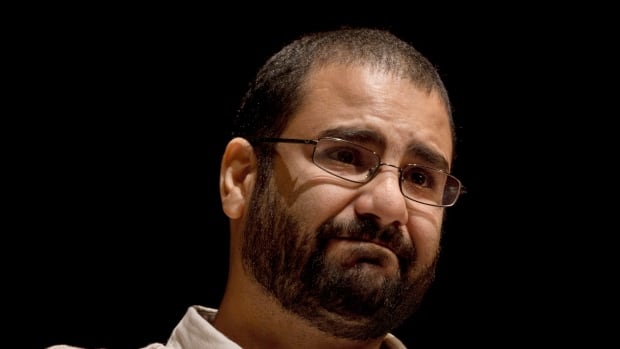

Alaa Abdel-Fattah, a U.K. citizen and one of Egypt’s most prominent political prisoners, began a full hunger strike on Tuesday in the Wadi El-Natrun prison complex north of Cairo, where he’s currently being held.

He plans to stop drinking water on Nov. 6, as world leaders gather in the country for COP27, the United Nations climate change conference.

He’s trying to draw attention to his own case, and those of the tens of thousands of other political prisoners in the country. His family is begging for his freedom, saying that if he’s not released, he’ll surely die behind bars.

“I’m really scared,” Seif told As It Happens host Nil Köksal. “I sometimes lose it … and I panic. But I try to pull myself together and remind myself that as long as he’s alive, then there is a chance.”

Seif is in London, where she recently met with members of the U.K.’s Foreign Office about her brother’s case after staging a sit-in outside the ministry. She’ll be heading to COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, too, to raise his case with British delegates and other world leaders.

“It’s not over until it’s over,” she said. “I’m scared. But I also understand that he’s fighting to live and he’s trying to maximize the potential of getting out. So we have to also help him in that fight and keep campaigning.”

Imprisoned for most of the last decade

Abdel-Fattah, 40, rose to prominence during the 2011 pro-democracy uprisings that swept the Middle East and in Egypt, and has spent most of the past decades behind bars.

He was first sentenced in 2014 after being convicted of taking part in an unauthorized protest and allegedly assaulting a police officer. He was released in 2019 after serving a five-year term but was arrested again later that year in a crackdown that followed anti-government protests.

In December 2021, he was sentenced to another five-year term on charges of spreading false news. He also faces separate charges of misusing social media and joining a terrorist group — a reference to the banned Muslim Brotherhood.

His family has also been a target of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s government. Seif has herself been imprisoned for her activism.

But with her brother starving in prison, she says her freedom tastes bittersweet.

“I can’t really feel that I’m free,” she said. “I can’t feel that it’s over until we’re all back together, reunited in a safe place.”

‘He looked like skin and bones’

For months, Abdel-Fattah has been on a partial hunger strike, consuming only 100 calories a day. Seif says the last time her mother saw him during her monthly visit on Oct. 16, he was barely able to stand.

“He looked very, very frail. He looked like skin and bones,” Seif said. “But he was in one piece.”

In a recent letter to his family, he said he plans to take his hunger strike to the next level, coinciding with COP27.

A group of 15 Nobel Laureates has written an open letter asking visiting diplomats and politicians to devote part of their agenda to Egypt’s estimated 60,000 political prisoners, and Abdel-Fattah’s case in particular.

Seif will be there as a UN-accredited civil society observer. So, too, will Rishi Sunak, the U.K.’s new prime minister.

Asked if she had a message for Sunak, Seif begged him to press for her brother’s freedom.

“If you don’t do that, the Egyptians would interpret this as a green light to kill Alaa,” she said. “Please, please, please, bring Alaa home with you.”

Abdel-Fattah has British citizenship through his mother, Laila Soueif, a math professor at Cairo University who was born in London.

Max Blain, a spokesperson for Sunak, said the U.K. government is “raising his case at the highest levels of the Egyptian government” and “working hard to secure Alaa Abdel-Fattah’s release.”

He said he could not say whether Sunak will raise the case at COP27.

An Egyptian government media officer did not respond to a request for comment from The Associated Press. Egyptian authorities have previously denied that Abdel-Fattah is on a hunger strike.

‘Alaa, to me, is not a symbol’

In his letter, which his family has translated into English, Abdel-Fattah wrote: “If one wished for death, then a hunger strike would not be a struggle. If one were only holding onto life out of instinct, then what’s the point of a struggle? If you’re postponing death only out of shame at your mother’s tears, then you’re decreasing the chances of victory.”

Abdel-Fattah’s other sister, Mona Seif, wrote on Twitter that regardless of whether her brother survives, he’ll have won his fight.

“If he makes it out alive … he would have done it using only his body and words,” she wrote. “If he doesn’t make it and dies in prison … his body will tell the whole world the truth.”

Sanaa Seif agrees with her sister. Yet, she struggles to see her brother through that lens.

“I feel like the political or symbolic battle, yes, has been won. But that doesn’t mean much to me. Alaa, to me, is not a symbol,” she said.

“I would rather that we lose the political battle and be, I don’t know, like [branded] in state media in Egypt as traitors or whatever, but have my brother back.”