Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s journey from a jail cell four years ago to winning the highest office in Brazil for a third time is a political comeback story like few others.

Yet the one-time trade union leader’s success in Sunday’s presidential election, defeating his bitter rival Jair Bolsonaro, is only the latest victory in a lifetime of triumph over adversity, which has made him one of the world’s most famous political names.

Born to tenant farmers in the poor north-east of Brazil, Lula spent his early years in a two-room shack with no electricity or running water before embarking aged seven with his mother and six siblings on a two week journey south by truck in search of a better life.

Decades later, he would draw on those hard lessons to explain his economic thinking. “I learned when I was still very young from my illiterate mother that I couldn’t spend more than I earned,” Lula, 77, told the Financial Times in an interview this year, while outlining why he could be trusted with the nation’s finances. “I don’t need any economists to tell me about [fiscal] responsibility.”

Lula’s personal story, his charisma and his record fighting hunger and poverty are the secrets of his political appeal in Brazil and abroad, despite long-running controversies over corruption and economic mismanagement during the governments led by his Workers Party (PT).

Perhaps best known for channelling the windfall profits from a commodity boom into social programmes during his 2003-10 presidencies, Lula’s signature welfare programme Bolsa Familia transformed the lives of millions of Brazilians.

“The Bolsa Familia programme, which took 40mn people out of poverty, was a revolution,” said Fernando Morais, his biographer and a political ally. “He managed to get 40mn people, four times the population of Portugal, to eat every day.”

In those days, Lula strode the international stage, winning the attention of political figures as diverse as Tony Blair, Fidel Castro and Vladimir Putin and heading a coalition of like-minded leftwing South America leaders.

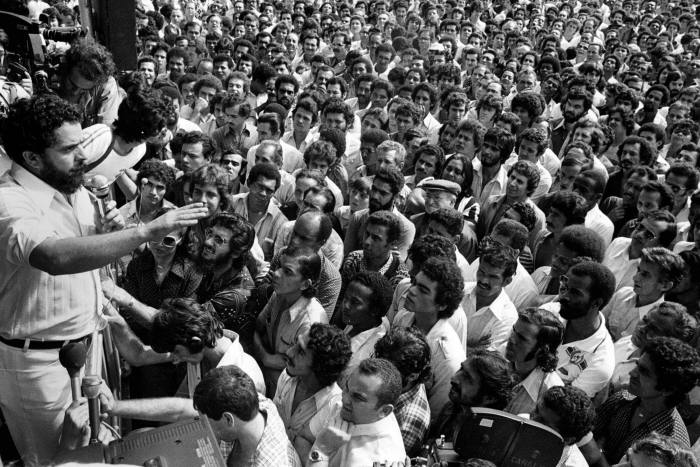

Few would argue with the life experience of a head of state whose first job was shining shoes and who never finished secondary school. Lula trained as a metalworker in the rapidly industrialising towns around São Paulo in the 1960s before embarking on a career as a union activist, where he clashed with Brazil’s military dictatorship over wage rises and was briefly imprisoned.

In 1980 he helped found the PT, Brazil’s main leftwing party, and after three unsuccessful attempts, finally won the presidency in 2002.

When Lula ended his second term in 2010, with an approval rating of 87 per cent and the economy growing more than 7 per cent a year, Barack Obama described him as “the most popular politician on earth”.

Yet only a few years later, Brazil plunged into recession under Lula’s handpicked successor Dilma Rousseff. The ex-president and several close aides were implicated in a massive corruption scandal centred on more than $2bn in bribes paid by state-run oil company Petrobras to business people and politicians.

Lula was accused of personally benefiting by way of a seaside apartment and a farm. He protested his innocence but was convicted, beginning a 12-year prison sentence in 2018, with supporters staging a round-the-clock vigil outside.

Despite starting the 2018 presidential election as the clear favourite, Lula had to watch from his jail cell as Bolsonaro won the election.

But less than 11 months after Bolsonaro was sworn in, Lula was released pending appeal. Last year the Supreme Court annulled his convictions in a decision which remains controversial, and deemed the presiding judge in the case biased.

Lula immediately vowed to fight the 2022 vote and win back the presidency, showing the fighting spirit which has characterised his life.

His gravelly voice is the result of a battle against cancer of the larynx more than a decade ago, and he has overcome tragedies in his personal life. His first wife died while pregnant along with his first son, and his second wife succumbed to a stroke in 2017. A life-long Catholic, he remarried this year and has five children from his previous relationships.

Although he has cobbled together a broad coalition with the centre and centre-right to win Sunday’s election, Lula remains a deeply polarising figure for Brazilians.

Many establishment figures who backed him in Sunday’s election were candid in private that they only did so to stop Bolsonaro, not because they believed in his policies. A section of the electorate remain unconvinced that Lula is innocent of corruption and think he should not be running at all.

Bolsonaro repeatedly played on Lula’s corruption convictions during the campaign, calling him a “nine-fingered thief” in a reference to the former metalworker’s loss of his little finger in a work accident when younger.

Business leaders worry that Lula has struggled to articulate a convincing vision for Brazil’s economy in the 21st century. Instead, he harks back to his earlier two terms, assuring audiences that his achievements speak for themselves.

His preference for state-directed economic development and a revival of oil refining and shipbuilding ring alarm bells for those who recall the economic missteps of past PT governments.

Lula finds it easier to convince doubters when he talks about the environment, referencing his record in government to dramatically reduce deforestation. Aides say he wants Brazil to take centre stage in the fight against global warming, with fresh commitments to preserving the Amazon rainforest and exporting renewable fuels.

His foreign policy thinking will be more controversial in the west. Lula has suggested that Ukraine and Nato are partly responsible for the war with Russia, has defended Cuba’s one-party regime and wants good relations with China.

Above all, he favours negotiation over confrontation. This may be unfashionable in today’s highly polarised world, but Lula remains one of the few global politicians to command respect from nations as diverse as the US, Russia, China and Germany.

“If I win the elections and this war is still going on, you can be certain that I am going to talk to the Europeans, the Americans, the Chinese and the Russians,” he told the FT. “Someone has to start talking about peace in this world.”

Additional reporting by Bryan Harris in São Paulo