This First Person article is the experience of Tiffanie Tri, a writer, policy leader, entrepreneur and community builder in Ottawa. For more information about CBC’s First Person stories, please see the FAQ.

If you asked me when I knew that my family were refugees, I couldn’t tell you. There was no single moment of realization — just scattered memories like puzzle pieces that don’t always seem to fit.

When we were kids, my parents would tell my sisters and me of their harrowing journey evading soldiers and pirates, how they survived the stormy waters of the South China Sea and arrived in Hong Kong.

After nine days at sea, they waited another three days on the ship just outside the city before the United Nations intervened and they were finally allowed to disembark. They stayed at a refugee camp for four months before they were sponsored to come to Ottawa in 1979.

Hearing these stories, I always felt like they were novel adventures that were somehow distant from my life in Canada. As a kid, I didn’t have the historical knowledge or understanding to anchor their significance.

In school, little was taught about the Vietnam War — just a few sentences sprinkled here and there in history textbooks. Movies about the Vietnam War were always told from the view of American soldiers in the jungles of Vietnam ripe for cinematic shots of mud, blood, and glory.

None of these Oscar-worthy performances resonated with the stories that I’d heard from my family, which retained vivid shards of hope and humanity despite the melancholy.

I guess it was no surprise that my passing interest faded into an easy ambivalence.

Asking my grandfather

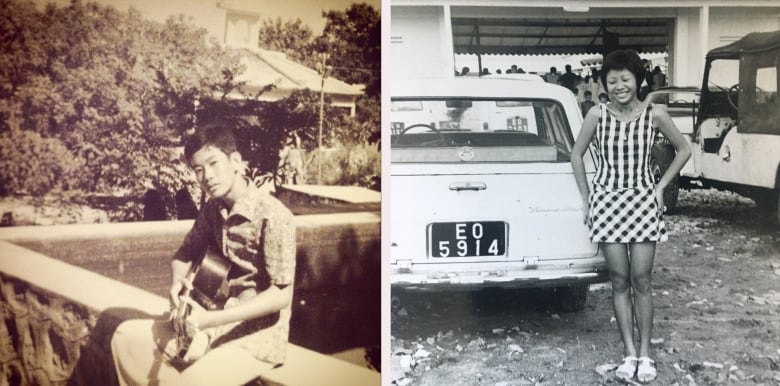

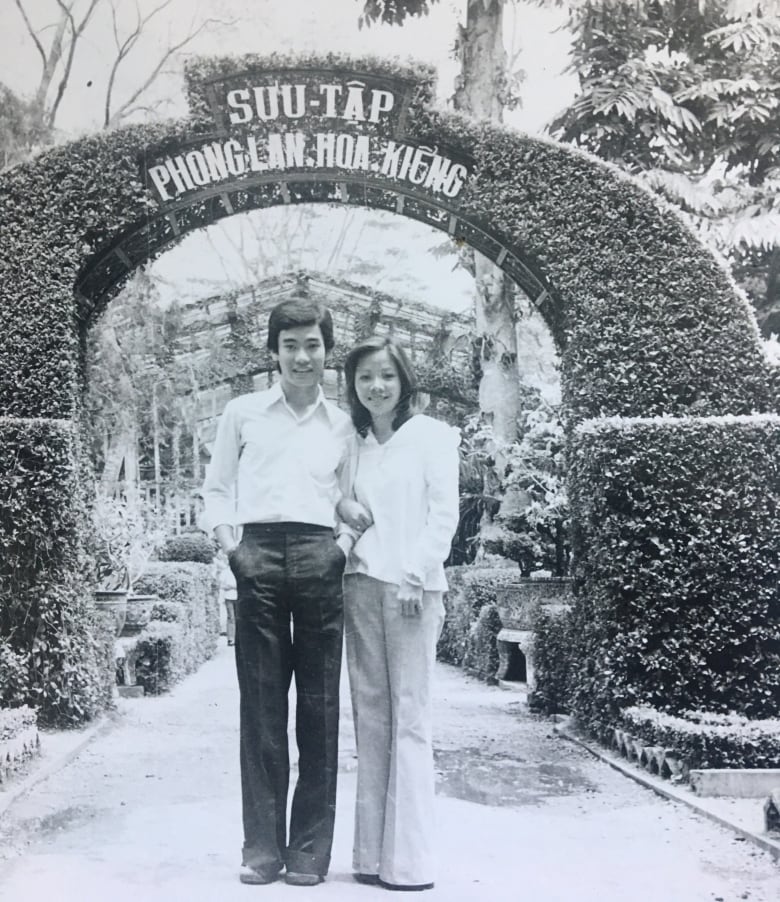

My maternal grandfather was the force behind our family’s move to the other side of the world. My parents were dating at the time and my dad joined my mother’s family on the perilous journey, leaving behind his own parents. They surrendered their fates to the ocean and the immigration system.

Though my parents shared their stories of what happened, it felt important to hear my grandfather’s perspective. He didn’t talk much about his past. Maybe it was the loss of my grandmother just a few years after arriving in Canada, or perhaps the stifling humility of starting over robbed him of the desire to talk about his life.

- Do you have a compelling personal story that can bring understanding or help others? We want to hear from you. Email us with your pitch.

At family gatherings, I would give the obligatory greeting “Hi gong gong!”

“That’s good, that’s good,” he would say in return, nodding in acknowledgement while simultaneously waving us away.

The first time I heard him sharing his story was at his baptism at the age of 89. The faintest trace of emotion crept into his voice as he spoke about how life changed drastically during the war, of being imprisoned and the numerous attempts he made to get his family out of the country.

With their savings dwindled by extortion and exorbitant prices charged by smugglers for a chance at freedom, my family made one last attempt to leave Vietnam. Moving like shadows, they boarded a boat with several hundred people. After nine days at sea, a violent storm thrashed the boat and many passengers lost consciousness.

When he came to the next morning, still alive, my grandfather couldn’t believe it. “Even after all that, we still couldn’t die!” he crowed in disbelief, still mystified after all these years.

Pandemic time

Increasingly I started to feel a pull, a nagging feeling that I needed to document these stories, and to honour this resolve and resilience.

I’d brush off these feelings to prioritize the hustle and grind of everyday life. It was only when the pandemic brought all events and activities to a halt that I felt like I had enough time.

I decided to try to capture this story, having met a film producer and director whose family also moved to Canada during the Vietnam War.

The process wasn’t easy. We connected with my grandfather on Zoom to learn about his story with my parents acting as translators across language and generations.

Peppering him with our list of prepared questions, we would wait, sometimes impatiently, as he picked through his memories, stoic as always.

Toward the end, we asked him what he missed most about Vietnam. He took a moment to reflect and said, “It’s hard to remember. Life feels like a dream.”

I had more questions but could see that he was fading as his answers became increasingly short. We said goodnight and ended the call.

That was the last time I ever spoke to him. Four weeks later, he was gone. Just as I’d started to break down the walls he’d built around his memories, and perhaps his grief, I found myself left with the ashes of what could have been.

I spent months berating myself for waiting so long to document his story, for waiting for the perfect conditions to come together and now it was too late.

Loss and untangling

As I grieve, a question echoes in my mind, one posed by the director Han Nguyen during our initial conversations. “When does the past and present meet before it splits out again?”

I think about this as I walk through Chinatown in Ottawa where my grandfather lived for the last several decades of his life, where Chinese herbal and acupuncture shops are slowly being replaced with trendy storefronts of microbreweries and cannabis dispensaries.

New construction will pave over my grandfather’s footprints even as I cling to the past. And it dawns on me, maybe there is no single moment where past and present meet. Instead, every step we take is a collision, every breath an interaction between past and present, a terse negotiation of our future.

It’s either a mundane travesty or an immense privilege, depending on how you look at it.

My message now is simple. Talk to your living ancestors. Unearth the stories of how they moved mountains, sliced through oceans and sideways stares.

And know that the same strength lies in you.

Do you have a compelling personal story that can bring understanding or help others? We want to hear from you. Here’s where you can pitch us.