Just beyond the entrance, people rest on raffia mats while others chat with friends or family who have come to visit. To the left of the entrance is a courtyard where dozens of residents are waiting to be attended to; in the open space ahead, women chat as they plait each other’s hair. Beyond all this activity in the foreground lies the chapel for those seeking solace.

The facility, known locally as the Saint Camille center, or just “St. Camille,” feels like the home of a very large family — one that houses up to 300 people from across West Africa in desperate need of care. For most of them, the center is the first place they will finally feel safe in a society where mental illness is stigmatized.

“Homeless and mentally ill women are being raped because there is this fetish belief that if a man sleeps with a mentally disturbed woman, he will be wealthy or no spiritual spell can affect his life,” explained Gregoire Ahongbonon who founded the first St. Camille center in 1991. “That is the reason why our first desire when we see these types of women is to take them off the street and give them a home.”

On CNN’s visit to the St. Camille center located in Tokan, on the outskirts of Benin’s largest city Cotonou, there were 120 women staying there, many of whom had been living on the streets when the team found them and brought them to this facility.

Seventy-year-old Ahongbonon told CNN he will often be driving his car when he sees someone who clearly looks vulnerable. He tries to engage them in conversation, explaining who he is and what his center does. He offers them a place to stay and access to medication — once a medical examination by the center’s qualified staff has been done — and then Ahongbonon and his team will try to establish if their newest arrival has any family.

Lodging and treatment at St. Camille are free to patients, with food, clothing and medicine provided by the organization, largely through charitable donations. If a patient is admitted to the center by a family member or friend, they are expected to pay a one-time contribution 5,500 CFA ($9). The government of Benin gives this center, and the six others under the St. Camille umbrella in Benin, no monetary support — though Ahongbonon told CNN that St Camille is exempted from paying customs duties on imports. The state also covers the facilities’ utility bills and recently began to pay a 3,000 CFA ($4.93) subsidy for three months for each person brought to the centers by local authorities. The Catholic Archdiocese of Cotonou donated the land on which the Tokan facility is built and benevolent members of the community, both local and international, also donate money, food and other supplies.

“We do not really have a [fixed] funding source. We have friends and donors who gift us whatever they have, we only live by the grace of God,” said Ahongbonon.

With facilities also in Ivory Coast and Togo, St. Camille fills a gap across West Africa in mental healthcare provision, left by the state and even the humanitarian sector, said Dr. Jibril Abdulmalik. But the consultant psychiatrist at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria also noted that few legal safeguards exist to protect people from other actors who might be predatory.

“The weak governance systems around mental health across the region is a problem that is really heightened by the circumstances of women who have mental illnesses and are abandoned by society and left to be vulnerable while living on the streets. Their removal to a place of safety as well as their autonomy to choose when to leave are not clearly spelt out and there is little or no supervision from governmental agencies,” said Abdulmalik who co-wrote the first Strategic Mental Health Plan for West Africa.

“Very few not-for-profit organizations are interested in providing help and interventions for persons with mental health challenges. Many organizations are more interested in communicable diseases such as HIV or malaria than [in] mental illness. So, it is really rare and commendable to note the dedication and service provision of St. Camille.”

Abdulmalik added: “Generally speaking, only 1 or 2 out of every 10 persons with mental disorders in West Africa are able to access mental health care services. This treatment gap is even worse when they are females, are pregnant or nursing a baby and have diseases such as HIV/AIDS.”

Three women, Odette, Ajoke and Abigail, all of whom are residents at St. Camille, told CNN their stories of pregnancy, mental illness and survival.

CNN is using only the names that these women told CNN they prefer, out of respect for their privacy and their circumstances. Each of the women consented to have their stories shared by CNN.

‘What would I do with the baby? My illness is bad enough’

Odette

Odette rubbed her shaved head with her left hand. Wearing a patterned maternity dress, she looked tired as she stood on swollen feet, leaning against a pillar outside the chapel.

She’d just returned from a routine antenatal check at the nearby hospital, Hôpital de zone d’Abomey-Calavi, where patients are regularly taken for care and procedures that St. Camille cannot perform.

“I fall sick a lot, and this has caused loss of appetite, vomiting, fatigue and insomnia,” said Odette, who was seven months pregnant when she spoke to CNN. “I want to give birth to the baby, but I don’t want to keep it. What would I do with the baby? My illness is bad enough.”

In February, firemen found Odette walking around in the city, looking disoriented, St. Camille staffers said. From the way she was dressed and spoke, it was clear to them that she was extremely vulnerable and so they took her to the hospital, where she was then referred to St Camille.

Once at St. Camille, the center’s psychiatrist Dr. Nicole Ahongbonon — who is also the founder’s daughter — diagnosed Odette with schizophrenia, as well as anemia.

Odette did not remember her age, but told CNN that for a long time the Saint Benoit Market, outside Cotonou, had been her home. “It was very scary there when the shop owners closed and went home leaving only me. I would hear babies crying and people talking to me but when I opened my eyes, there would be nobody.”

The details of life before that were also patchy. All Odette could remember was that her family was from a place called Aze Gõn, though attempts by the center’s staff to locate them have been unsuccessful.

Ahongbonon said one of the biggest challenges his team faces is that families often want nothing to do with his pregnant patients or their children. Pregnancy is a time when a woman needs as much support as she can get, he explained, and this is particularly important for women who also have a mental disorder.

Odette also described being sexually abused for years by men in the market and getting pregnant multiple times as a result. Women traders at the market confirmed to CNN that she had indeed lived there and had been pregnant more than once.

According to Sister Pascaline Agoton, St. Camille’s head nurse, Odette is often in denial about her current pregnancy. “She still has some bad days when she cries, she is erratic or simply in a foul mood and rejects that she is pregnant. We suffered this in the early days when she first came here,” Agoton explained. “Today, she is aware and accepts her pregnancy and willingly takes her medicines.”

Agotons was once herself a patient at the center and understands better than most the stigma of living with a mental health condition and the vacuum that the lack of family support leaves. “Many family members reject them because of their mental state. Some families drop them at our gate and run away just because they don’t want to pay the 5,500 CFA ($9). They only focus on the money, forgetting the patient also needs family support in order to feel loved and recover quickly,” she said.

The nurse, whose training was paid for by Ahongbonon, said she’d been lucky to have her family’s support when she was admitted to St. Camille in 2004 and diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

On May 10, Odette gave birth prematurely to a baby girl. She has not changed her mind about keeping the child and so the staff at the center are making plans for what to do next.

Odette will remain at the mental health facility until the team can find and send her to the care of her family — but only if they want her. If not, she too will become a permanent resident, like many others who call St. Camille their home.

‘Our family would be described as the one with a mad sister’

Ajoke

With golden brown tips to her braided hair dangling on her shoulders, it is impossible to miss Ajoke.

St. Camille has been home for the 35-year-old Nigerian mother of four since 2016, when Ahongbonon and his team found her outside in Cotonou one night, naked and visibly pregnant.

As they tried to establish who she was and where she was from, Ahongbonon recalled that she had told them her name was Ajoke and that she was from Lagos, Nigeria.

Ajoke had once been married, but said she was moved out of her marital home, to live with her husband’s grandmother, and then forced to leave the family altogether when his grandmother died.

“I did not know that I was sick,” she told CNN. “I know that I wasn’t sleeping… but [my husband and his mother] would tell me that I was behaving abnormally.”

She didn’t remember if she had had similar episodes during her first two pregnancies, but said that during her third pregnancy, she woke up one night insisting that she could hear the cry of a baby. ”I would talk to myself and hear voices or a baby crying.”

Facing homelessness and distraught at having lost her children (her husband kept custody of the two older ones), Ajoke said she just began walking and ended up in Benin, about 140km from Lagos.

A psychiatrist working at the center at the time diagnosed her with schizophrenia, and the medical examination also revealed that Ajoke was HIV positive, her status only compounding the then-29-year-old’s problems.

“Ajoke’s labor day was a very difficult one because no one wanted to touch her because of her disease,” Ahongbonon recalled. “Once the doctors heard what she was suffering from, they were scared.”

She went on to give birth at the hospital, after which her child was placed with a family for adoption.

“Based on the psychiatric state of their mothers, we decide if placing the child with a family is best for the child or if a family member is willing to take in the child. If we see that the mother is in a good enough state to care for the child, we leave it with her but not without constant supervision,” Ahongbonon explained, adding: “When the women get better, [they] themselves decide if they want the babies adopted or returned to them. We facilitate this and have never ever collected money or gifts or any kind of compensation for it.”

Mental health expert Abdulmalik told CNN women like Ajoke have little power when it comes to deciding what happens with their babies, or their own bodies. Excluding Ghana, he called mental health legislation across West Africa “weak and obsolete.” “Protection of their human rights and decision-making autonomy is essentially non-existent,” he said. “Their access to quality care, rights to keep their children or their reproductive options like their choice to use contraceptives or not are not offered to them.”

As Ajoke’s mental health began to improve, she said she missed home. In 2018, two years after she first arrived at St. Camille, a man she identifies only as Justin began coming to visit her and promised to take her back to her family in Nigeria.

Despite Ahongbonon’s objections — he expressed doubts about Justin’s intentions — Ajoke said she still decided to go with him, sneaking out of the facility.

“I thought he was taking me to Nigeria,” Ajoke said, shaking her head as she remembered. ”But he took me to his house in Cotonou instead and was sleeping with me … He sometimes beat me up and starved me too. I got pregnant again.”

Several additional traumas followed, including a reunion with her family — who Justin in fact did know — that ended with Ajoke also being rejected by them, and then abandoned on a roadside close to St. Camille.

“[My family] didn’t want people to see me because [they] would be described as the one with a mad sister,” Ajoke said. “[This] means nobody would want anything to do with us or marry from our family because they don’t want to be associated with such negativity.”

In July 2019, she had her fourth child and this baby was also placed with a family for adoption.

Three years on, Ajoke still wishes she could return home to Nigeria and be with her eldest children, but her family does not support her return, she told CNN. The center is the only home she has.

“Here, I know they will give me my medicines which I now know are the most important if I want to stay well,” she said smiling. “I cannot leave them.”

‘I’m happy here. They give me medicines and food’

Abigail

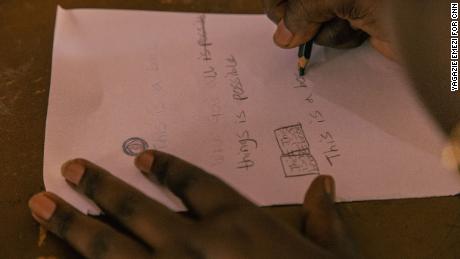

Abigail’s life before St. Camille was marked by violence. Like the other women CNN spoke to, Abigail said she could not remember many of the details of her past, particularly her childhood.

She talked about hearing voices when she was growing up, of family members who thought she was possessed by evil spirits and of having to fend for herself from a young age. As she crossed Cotonou scavenging for food, she soon came to live in a neighborhood settled by traders – a place that other residents of Cotonou refer to as “the ghetto”.

“I returned there very often and always got food, so I decided to stay there. Nobody ever came to look for me,” she said, holding close a blue plastic bag that contained her food bowl and matched her top and the rosary around her neck.

But alone and vulnerable, Abigail says some men took advantage of her. ”I still remember how they used to beat me and give me drugs and sleep with me, before giving me something to eat,” she said, pulling up her right sleeve to show some of the scars – long darkened gashes that look like strokes of a cane.

It was in 2015 that she was alerted to teams at St. Camille, by a man who told Agoton that he was familiar with the center helping the mentally ill. She was five months pregnant at the time. ”Someone informed us that there was a pregnant woman [Abigail] in a ghetto and that we needed to do something,” said Agoton.

Like Ajoke, Abigail has schizophrenia and is HIV positive. The medical staff at St. Camille immediately put her on a mother-to-child transmission prevention program, which includes provision of antiretroviral treatment and safer delivery options to prevent passing the virus onto her baby.

Smiling broadly as she held on to her rosary, Abigail told CNN that her baby was adopted and taken abroad. “I am happy here,” she said’. “They give me my medicines and food and I like helping in the kitchen.”

—-

If you or someone you know might be at risk of maternal mental health disorders, here are ways to help.

If you are in the US, you can call the PSI HelpLine at 1-800-944-4773 or text “Help” to 800-944-4773.

—-

Edited by Eliza Anyangwe and Meera Senthilingam