Dozens of public health labs across the country now use a more generalized test for orthopoxvirus, a larger category that includes monkeypox, smallpox and other viruses. Two biotechnology companies, Roche and Abbott, have announced plans to roll out monkeypox PCR tests, although right now, their test kits are for research only.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says it’s exploring ways to get monkeypox-specific testing out to states.

There are already 74 labs across 46 states — part of a network known as the Laboratory Response Network — that are “using an FDA-cleared test for orthopoxviruses,” CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky said Thursday.

Current capacity is around 7,000 of these tests weekly, with the potential to expand if needed.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, said a lot of that capacity “was set up in response to the threat of biological weapons, and smallpox is the most worrisome orthopoxvirus.”

The testing that CDC does is more specific to the monkeypox virus, and the agency can genetically sequence samples, as well. For example, it was by looking at the viral genetic code of the first US patient — a man in Massachusetts who had recently traveled to Canada — that researchers were able to see that his case of monkeypox closely matched that of a case in Portugal.

However, Dr. Jennifer McQuiston, a veterinarian and deputy director of the CDC’s Division of High Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, underscored that the testing that goes on at CDC isn’t really necessary for patient care.

“The orthopox test that’s in place is an actionable test,” she said.

Experts say that action may include isolating patients, making treatments and vaccines available, and contact tracing to determine who else might have been exposed to the virus.

Because other orthopoxviruses aren’t spreading in countries where they aren’t endemic like the US, one can assume that a positive orthopox test here is indeed monkeypox, according to Adalja.

“I think that more diagnostic tests closer to patients is better. Commercial assays are even better,” Adalja said. “But the fact is, there are no other orthopoxviruses out there right now.”

He doesn’t believe that a lack of monkeypox-specific testing is hindering the public health response “because an orthopox-positive [case] is going to be monkeypox until proven otherwise in this scenario that we’re in right now.”

He added that this is a very different situation from the Covid-19 testing stumbles of 2020, when the world was dealing with a novel coronavirus without a major testing alternative, meaning it was often difficult to tell Covid-19 apart from other respiratory viruses like the flu. Monkeypox, on the other hand, we’ve known about for decades, and there’s a plan in place.

“It’s not the same as Covid,” Adalja said.

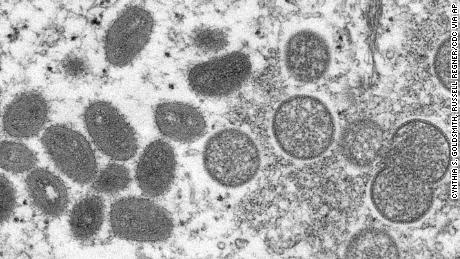

Identifying monkeypox

Monkeypox symptoms can include fever, headache, muscle aches and swollen lymph nodes. A characteristic of the disease is a rash that results in lesions or pustules. This can happen anywhere on the body, often on places like the face, hands and feet. In the current outbreak, some cases have caused lesions in the genital or groin area, according to health officials.

The process for identifying a monkeypox case in the United States begins with a person noticing possible symptoms and seeking medical care. Their provider can contact a local or state health department to collect a specimen for orthopox testing, said Chris Mangal, director of public health preparedness and response at the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

At this time, the CDC is recommending the collection of two specimens — swabs of lesions.

“When they run that test, and if that test comes back positive, they will report presumptive positive for non-variola orthopoxvirus. And that presumptive positive is actually good enough — that, combined with what you’re seeing in terms of the patient presentation — to give them a sense that ‘we should take public health actions here,’ ” Mangal said.

The second specimen and the test result are sent to the CDC for its own testing.

“The CDC and the public health labs actually work closely, hand-in-hand, on this testing,” Mangal said.

During the monkeypox outbreak, the process for confirmatory testing has been “good enough for the phase we’re in right now” because there has not been a high number of cases, she said.

“If we get into the scenario where we’re seeing a significantly higher number of cases of monkeypox, it is my belief that CDC will then work with the [US Food and Drug Administration] and the public health labs to ensure they have this confirmatory capability,” she said, adding that there are a few scenarios that could play out if that happens.

“We can have public health labs developing their own lab-developed tests,” Mangal said. “If this rose to an emergency scenario, similar to Covid, laboratories could work through the FDA to obtain an emergency use authorization for confirmatory tests.”

But overall, Mangal said, she does not see the current outbreak developing into a major emergency. For the general public, “it’s my opinion that they should not be overly concerned,” she said.

The current capacity for monkeypox testing is “not a major public health concern” in general, Adalja said, but there is still room for it to move faster or be more widely available.

“It would be great if Quest and LabCorp could do it. It’d be great if there were kits that people could put in sexually transmitted infection clinics to definitively diagnose,” he said. “But I don’t think right now you’re hampering the public health response, just because there’s no other orthopoxvirus circulating.”

Even if the CDC shifts monkeypox-specific testing to state public health labs, getting confirmatory results could take time, Adalja added.

“Even though we’re talking about state public health labs and members of the CDC’s Laboratory Response Network being able to do orthodox PCR, it’s still a step — it still involves paperwork, it still involves making phone calls, that dissuades people from doing it, that has a lag built into it,” Adalja said.

“If you work in an STD clinic in some city and you have that kit there, or you have a lab that’s right in your town that does it, that makes it so much easier,” he said.

Plans for monkeypox PCR tests

Roche and Abbott’s planned monkeypox PCR tests are separate from the CDC’s plans.

None has received a green light from the FDA, and both companies said last week that their tests are intended for “research use” — though they are leaving the door open to tackle future testing needs.

Even if it doesn’t become necessary to expand testing in countries like the US, these moves could benefit other countries, including those in Western and Central Africa where the monkeypox virus has long been endemic.

“Some of the resource-poor countries where these diseases are endemic sometimes have a clearer path to getting these tests in people’s hands than in the United States, where there’s so much regulation and it’s so hard to do a point-of-care test,” Adalja said.

“I do think there’s an advantage to having these tests in endemic countries so that people can get diagnoses quickly,” he added. “You can find outbreaks much faster. You can deploy the smallpox vaccine faster for monkeypox.”