Nearly a month later, the memories of that April 29 event feel distant for Sanchez, a 42-year-old mother of two who works at a local beauty school.

Grief and frustration have set in, and prayers have replaced the laughter that once echoed throughout the venue that sits on the edge of a town 80 miles west of San Antonio. Since Tuesday, residents have gathered daily to mourn after sorrow burst into what feels like nearly every household in this town of about 16,000 people.

In downtown Uvalde, two of the longest federal highways in America — US Highway 83 and US 90 — intersect just like the feelings of many families this week. In one corner, portraits of high school seniors line the lawn outside City Hall. At another corner, flowers were placed next to white crosses bearing the names of each of Tuesday’s 21 victims along the town square’s fountain.

“This was something that should have never happened,” Sanchez said. “Our prayers are with everyone because everywhere I go, everyone was affected whether you had a child in there or not. If you didn’t there’s guilt because you get to go home and feel happy with your family when you know that they’re never going to be the same.”

‘We run in packs’

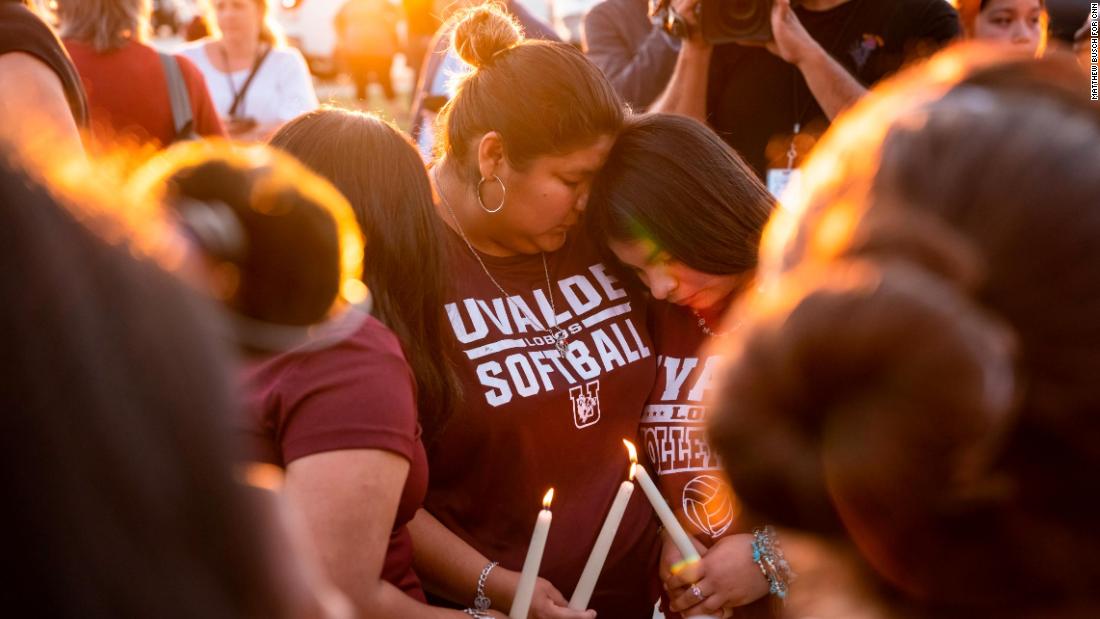

Wearing maroon-colored clothing in Uvalde is not unusual. But the amount of people wearing the city’s colors has multiplied over the week and taken on new meaning.

For decades, parents, abuelas and children have filled the stands at the Honey Bowl Stadium every fall to cheer for the Uvalde Coyotes during Friday night football games. After farmers and ranchers return home from the fields and many businesses shut down, residents routinely make their way to the stadium to watch one of their favorite pastimes.

As Uvalde attempts to find solace after Tuesday’s shooting, Marie Alice Ramos says there was nothing she could tell her friends or family that would make them feel better. Wearing her maroon T-shirt, she says, signaled something beyond words.

“It’s a statement. It shows that we are trying to be unified as one in a community that has been devastated,” the 45-year-old bartender said after she and a group of family members, all wearing maroon, stood near Robb Elementary late Wednesday.

“We run in packs. Coyotes run in packs,” one of her cousins, Jessica Ahoyt, who was standing next to her said while embracing her daughter.

Ahoyt’s daughter then added, “Once a Coyote, always a Coyote.”

Ramos’ cousin Irma Garcia, one of the teachers killed in the shooting, was a Uvalde High Coyote 30 years ago.

The words “Howling’ thru ’92,” and an image of a coyote howling to the moon blaze the cover of Garcia’s high school yearbook. Its pages show her and her husband, Joe, in the early years of their love story.

For more than two decades, Garcia dedicated her time to her own children and those of others. She nurtured them, hoping that one day they would go to college.

“Her commitment to the children in the school went above and beyond, to another level. She made the biggest sacrifice that anybody could make out there,” Ramos said. “She is a true hero.”

‘Uvalde Strong’

Surrounded by centuries-old oak trees, three or four generations of Mexican American families have lived in the same homes — often filled with the aroma of carne asada grilling on the weekends and the sound of Tejano, country, banda and other Spanish-language music.

The summer is perfect for tubing in some of the clearest rivers in Texas — the nearby Nueces, Frio and Sabinal. And throughout the year, weekends are reserved for hours-long hikes at Garner State Park, shopping in San Antonio and celebrations like quinceañeras and weddings.

But many of those plans were canceled this weekend as everyday life has been shattered.

Graduating seniors dressed in their cap and gowns had walked through the halls of Robb Elementary on Monday with their younger siblings, nieces and nephews cheering for them. The rest of their senior week activities were halted, including their graduation.

As families waited for answers on the condition of their children Tuesday and later faced devastating news, people across Uvalde initially hunkered down at home to pray among loved ones or simply keep each other close.

But within hours, many said they were growing restless and began searching for ways to support their neighbors as the town begins the grueling process of burying the 21 victims. By Thursday, the victims’ remains were released to funeral homes, where family members had dropped off clothing and other items for the burials.

A family built wooden crosses for each of the victims and delivered them to Robb Elementary School. Hundreds waited for hours under the Texas heat to donate blood. Several people designed artwork for new maroon T-shirts resembling those seen in other communities after a mass shooting.

“Uvalde Strong,” the T-shirts read.

Omar Rodriguez, the owner of a car detailing business, prepped 250 hamburgers to raise funds for the victims’ families. At a friend’s lot on Main Street, Rodriguez set up a large grill, tables and supplies to cook while his family and friends grabbed rags and soap to wash cars for a donation.

Rodriguez says he couldn’t stay at home thinking there could be something he could do to help.

“This is a good little town. There’s nothing but love here,” the 24-year-old said.

‘Our babies’

There have been two words emerging repeatedly in conversations as people picked up breakfast tacos inside the Stripes convenience store, served food and drinks at a popular Mexican restaurant, or bought meat for carne guisada at the H-E-B grocery store.

“Our babies,” residents said. For them, the children killed at Robb Elementary were simply family.

Lucia Guedea, a 53-year-old city worker in Uvalde, says most, if not all residents, had a connection to the victims. They were going to school together or were classmates with their parents, they know their tias and grandparents, or watched them play soccer, basketball, softball or T-ball with their own kids.

“They (children) are the center of our activities around here,” Guedea said.

Earlier this week, Guedea’s 11-year-old daughter, Raquel, and 20 other children walked down the aisle of the Sacred Heart Catholic Church. In silence, they held a single red rose as a priest called the names of the victims:

Eva Mireles

Amerie Jo Garza

Xavier Javier Lopez

Uziyah Garcia

Jose Flores Jr.

Alexandria “Lexi” Rubio

Irma Garcia

Eliana “Ellie” Garcia

Annabell Guadalupe Rodriguez

Tess Marie Mata

Eliahana “Elijah” Cruz Torres

Nevaeh Bravo

Jacklyn Jaylen Cazares

Jailah Nicole Silguero

Makenna Lee Elrod

Jayce Carmelo Luevanos

Alithia Ramirez

Layla Salazar

Maite Rodríguez

Rojelio Torres

Maranda Mathis

“I trust that the children, the children will help us do the work,” said Archbishop Gustavo García-Siller from the Archdiocese of San Antonio at the end of the bilingual Mass.

After the Mass ended, Guedea said her daughter did not attend Robb Elementary but wanted to make sure that she did her part.

“I felt like happy that I was able to like honor them and their spirits,” Raquel said.

Four of the children and one teacher killed were members of the parish.

In the days since the massacre, parents in Uvalde held their children’s hands and pushed their strollers to visit the school, attended vigils, and prayed at religious services. Faith is a remedy residents hope will guide them through their grief.

At the site of a makeshift memorial, they’ve brought their children to meet comfort dogs and grab free raspas (snow cones) being handed out by people from nearby towns.

A 10-year-old girl who attends Robb Elementary held her father’s hand tight and did not say a word when a woman who had set up a table at the town square with care packages and stuffed animals first told her she could grab anything she wanted.

It wasn’t until after her father encouraged her that she grabbed a unicorn. He said he had skipped work because he needed to be near his daughter, who is very shy and lost a cousin in the shooting.

In a town where life revolves around its youngest residents, festivals and community events always have something to entertain children in the absence of places like Peter Piper Pizza or Chuck E. Cheese, says Sanchez, the staffer at the beauty school.

The community is torn between mourning those whose lives were cut short and trying to erase the anguish the massacre has brought to their children’s faces. Locals like Sanchez say it will take time for them to heal but they know their “babies” will push them to do so from heaven or Earth.

“What we really live for is our kids. Every day we get up, go to work, and it’s mainly to make something better for them. It’s what keeps us going, honest to God,” Sanchez said.