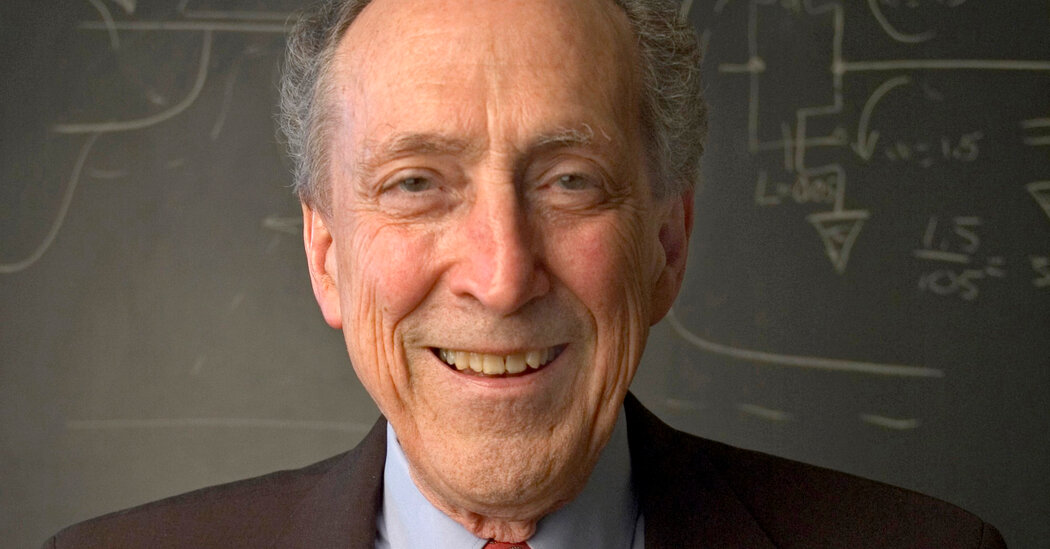

Robert H. Dennard, an engineer who invented the silicon memory technology that plays an indispensable role in every smartphone, laptop and tablet computer, died on April 23 in Sleepy Hollow, N.Y. He was 91.

The cause of death, at a hospital, was a bacterial infection, said his daughter, Holly Dennard.

Mr. Dennard’s pioneering work began at IBM in the 1960s, when the equipment to hold and store computer data was expensive, hulking — often room-size machines — and slow. He was studying the emerging field of microelectronics, which used silicon-based transistors to store digital bits of information.

In 1966, Mr. Dennard invented a way to store one digital bit on one transistor — a technology called dynamic random-access memory, or DRAM, which holds the information as an electrical charge that slowly fades over time and must be refreshed periodically.

His discovery opened the door to previously unimaginable improvement in data capacity, with lower costs and higher speeds all using tiny silicon chips.

DRAM has been the basis of steady progress in the decades since. High-speed, high-capacity memory chips hold and quickly shuttle data to a computer’s microprocessor, which converts it into text, sound and images. Streaming videos on YouTube, playing music on Spotify or Apple Music and using A.I. chatbots like ChatGPT depend on them.

“DRAM has made much of modern computing possible,” said John Hennessy, a computer scientist and chair of Alphabet, Google’s parent company.

Mr. Dennard also devised a concept that has served as a road map for future advances in microelectronics. Debuted in an initial paper in 1972, and fleshed out in another two years later, he described the physics that would allow transistors to shrink and become more powerful and less costly, even as the energy each one consumed would remain almost constant.

The principle, known as Dennard scaling, was complementary to a prediction made in 1965 by Gordon Moore, who went on to co-found Intel. Mr. Moore claimed that the number of transistors that could be crammed onto a silicon chip could be doubled about every two years — and that computing power and speeds would accelerate on that trajectory. His prediction became known as Moore’s Law.

Moore’s Law concerned the density of transistors on a chip, whereas Dennard scaling mainly concerned power consumption, and by 2005, it reached its limits: Transistors had become so tiny, they began to leak electrons, causing chips to heat up and consume more energy.

But Mr. Dennard’s approach to identifying challenges in the technology, researchers say, has had a lasting impact on chip development.

“Everybody in semiconductors studied his principles to get where we are today,” said Lisa Su, chief executive of Advanced Micro Devices, a large chipmaker, and a former colleague of Mr. Dennard’s at IBM.

Robert Dennard was born on Sept. 5, 1932, in Terrell, Texas, the youngest of four children. His father, Buford Dennard, was a dairy farmer, and his mother, Loma Dennard, was a homemaker who also worked in a school cafeteria.

The family moved east when Robert was a small child, and he began his education in a one-room schoolhouse near Carthage, Texas. The family later moved to Irving, then a small town, when his father got a job with a fertilizer company there.

Growing up, Robert developed an appreciation for the arts, reading the H.G. Wells stories and Ogden Nash poems that his oldest sister, Evangeline, had left behind when she departed Texas to be an Army nurse during World War II. In an oral history interview for the Computer History Museum in 2009, he recalled listening countless times to an album of Sigmund Romberg operettas. “She left me behind some really good things to start off some kind of intellectual career,” he said of his sister.

In high school, he was a good student, especially in math and English, and had planned to go to a nearby junior college. But his aptitude for music offered a different path. He played the E-flat bass in his high school band, and when the director of the Southern Methodist University band visited, he offered Robert a scholarship.

“That was my opportunity,” Mr. Dennard recalled.

Though music was his entry point, he earned undergraduate and master’s degrees in electrical engineering at the university. He later received a Ph.D. from the Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University.

In 1958, Mr. Dennard was hired by IBM, where he spent his entire career until retiring in 2014.

He was married three times. He and his second wife, Mary Dolores (Macewitz) Dennard, divorced in 1984, and in 1995 he married Frances Jane Bridges.

In addition to his daughter and his wife, Mr. Dennard is survived by another daughter, Amy Dennard, and four grandchildren. His son, Robert H. Dennard Jr., died in 1998.

Over his career, Mr. Dennard produced 75 patents and received several scientific awards, including the National Medal of Technology from President Ronald Reagan in 1988 and the Kyoto Prize in advanced technology from the Inamori Foundation, in Japan, in 2019.

In the 2009 interview, when Mr. Dennard was asked what advice he would give a young person interested in science and technology, he pointed to his own “very humble upbringing” and said “anybody can participate in this.”

“There is opportunity there,” he said. “These things don’t happen by themselves. It takes real people, making these breakthroughs.”