It was long anticipated, and now it’s here.

The global weather pattern El Niño has returned for the first time in seven years, according to the World Meteorological Organization, setting the stage for further extreme weather and soaring temperatures.

The UN agency made the declaration on Tuesday, after months of forecasting suggesting the weather pattern was likely to return.

“The onset of El Niño will greatly increase the likelihood of breaking temperature records and triggering more extreme heat in many parts of the world and in the ocean,” WMO Secretary-General Prof. Petteri Taalas said in a statement Tuesday.

While it’s a natural phenomenon, this is the first time El Niño has happened on top of a baseline of so much human-caused warming, making the WMO say it is “playing out in uncharted waters.”

Here’s a breakdown of how El Niño works, and what its return could mean for Canada.

Wait, what is El Niño again?

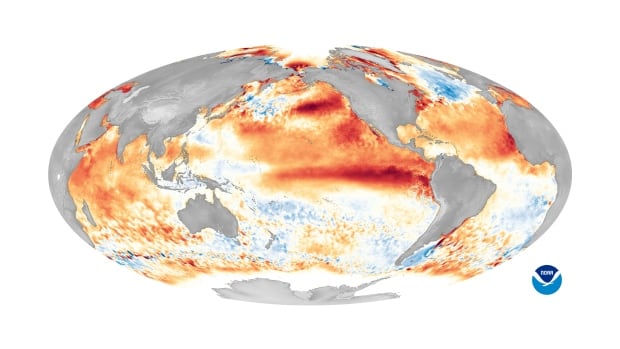

El Niño is a naturally occurring climate pattern associated with warming of the ocean surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean.

(The opposite is La Niña, where the surface of the Pacific ocean cools).

Together, the El Niño/La Niña cycle is referred to as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

El Niño occurs on average every two to seven years, and typically lasts nine to 12 months.

It has been linked to extreme weather conditions, from heavy rainfall in South America to drought in Australia and parts of Asia.

The WMO said there is a 90 per cent probability this latest El Niño event will continue through the second half of 2023 and is expected to be at least of “moderate strength.”

The world’s hottest year on record, 2016, coincided with a strong El Niño — the last one before this year.

How does this relate to climate change?

Regardless of where it is in the El Niño/La Niña cycle, the earth is warming due to increased CO2 in the atmosphere.

The past three years of La Niña still saw some of the warmest global temperatures on record.

Experts say the warming could have been even more pronounced without that cooling phenomenon.

A WMO report published in May predicted there is a 98 per cent chance that at least one of next five years will be the warmest on record, beating the record set in 2016.

“I think it’s fair to say that with a with an El Niño that is occurring in a background state of global warming, that extreme weather will become more extreme,” said John Gyakum, a professor in McGill University’s atmospheric and oceanic sciences department.

WATCH | World Meteorological Organization explains the effects of El Niño:

What can we expect in Canada?

Historically, Canada is mostly affected by El Niño during winter and spring. Milder than normal winters and springs occur in western and central Canada.

“I would bet a few loonies on the fact that with El Niño, especially if it’s strong and it’s large, we’re in for a warmer than normal winter coming up,” said Dave Philips, senior climatologist with Environment and Climate Change Canada.

It could also mean fewer hurricanes in Atlantic Canada, he said.

During the last El Niño, in the winter of 2015-2016, winter in Canada was 1 C to 5 C warmer than normal across all provinces, with especially unseasonal warmth in Quebec, the central Prairies, and Yukon.

Warmer temperatures won’t necessarily lead to an easier winter, Gyakum said.

“It doesn’t mean that you’re going to have balmy weather. On the contrary, we can have very inclement weather,” he said, pointing to Quebec’s devastating 1998 ice storm, which also occured during an El Niño year.

B.C. has already seen more than 50,000 hectares of land burn this year thanks to an unusually warm and dry May. With June temperatures also forecast to be above average, meteorologist Johnanna Wagstaffe says forecasters are preparing for a difficult summer.

What about this summer?

Canada doesn’t tend to see a direct impact from El Niño until later in the year, said Gyakum.

“Most of the impacts of El Niño occur during the winter time when the jet streams are more active,” he said.

Philips said it’s unclear to what extent the global weather pattern has affected the summer so far, and Canada’s record wildfire season.

But he said certain extreme weather events could potentially be linked to El Niño, including heat waves in the U.S. south and Mexico, the U.K and China.

“I wish I had more of a connection with summer weather and El Niño, but science hasn’t really gotten there yet,” he said. “It takes a lot of working and modelling and statistical analysis to determine that.”