In a first, a team of scientists from India, Japan and Europe has found evidence of gravitational waves in the universe. The team included researchers from Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee (IIT-R).

According to the results published in two seminal papers in the Astronomy and Astrophysics journal, the team monitored data from pulsars using six of the world’s most sensitive radio telescopes, including India’s largest telescope, uGMRT.

Pulsar is a highly magnetised neutron star that emits beams of electromagnetic radiation out of its magnetic poles.

Read Also

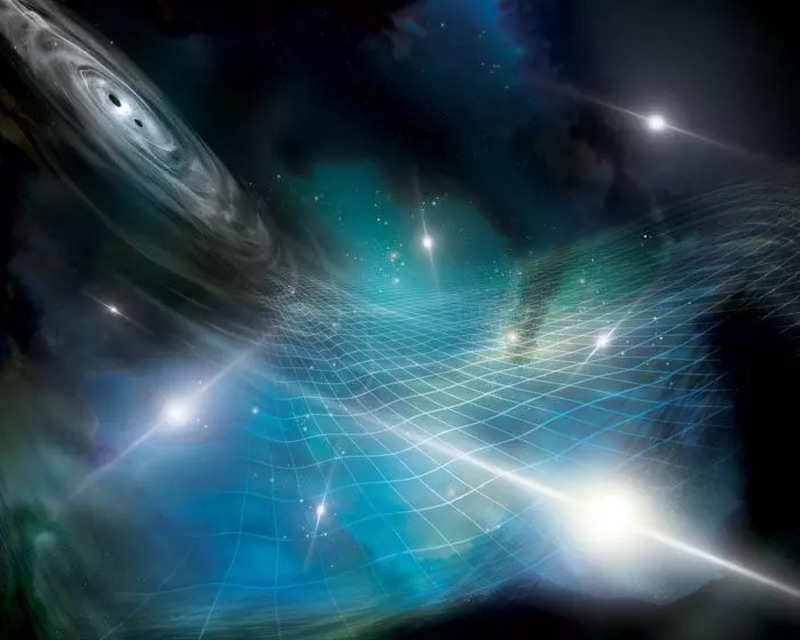

The telescope, located in Pune, is operated by the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics (NCRA) and was instrumental in the discovery of ripples in the fabric of space-time, which are called nano-hertz gravitational waves. Such waves also originate from a dancing monster black hole pair believed to be crores of times heavier than our Sun.

The relentless cacophony of these gravitational waves from a large number of supermassive black hole pairs create the humming of our universe.

“These results have culminated due to years of efforts of many scientists, including early career researchers and undergraduate students. I am very grateful that IIT Roorkee has been able to constantly contribute in various ways in achieving these results,” said professor Arumugam, Department of Physics, IIT Roorkee.

Read Also

How pulsars helped detect waves

Pulsars are called cosmic clocks and they emit radio beams that are seen as flashes from the Earth regularly. Astronomers monitor these beams or signals using radio telescopes.

Albert Einstein said that gravitational waves change the arrival times of these radio waves and affect the measured ticks of our cosmic clocks. Due to irregular arrival times of radio waves from pulsars it was deduced that the universe is filled with gravitational waves.

Since these changes are extremely tiny, astronomers need sensitive telescopes and a collection of pulsars to separate these changes from other disturbances.

The team also consisted of members of the European Pulsar Timing Array (EPTA) and Indian Pulsar Timing Array (InPTA) consortia, as well as PhD student, Jaikhomba Singha.

FacebookTwitterLinkedin

end of article