It was a big week for black hole news.

For the first time, astronomers have seen close up details of a powerful jet of ejected material emerging from the region surrounding a supermassive black hole.

And another team has released computer simulations showing how a smaller black hole can spit out remnants of a star in the process of devouring it.

Black holes have voracious appetites, swallowing entire stars or huge clouds of gas, which disappear into their gravitational maw. But before being swallowed, the material often swirls around under the influence of their powerful gravitational field at tremendous speed, like water spinning down a drain. In the process, the material is heated up until it glows, creating what’s known as an accretion disc.

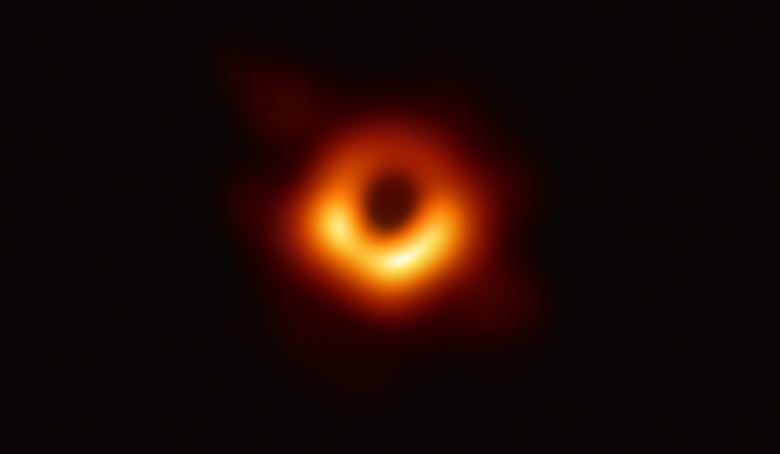

In 2017, NASA released the first-ever image of an accretion disc. It surrounded the supermassive black hole at the centre of galaxy Messier 87 (M87). It lies 55 million light years from Earth, and is estimated to be about 6.5 billion times the mass of our sun.

The black hole itself in the centre of the disc cannot be seen, because no light escapes from it — but we can see the hot, glowing accretion disc around it.

Through a process not completely understood, some of this hot material is shot out from the top and bottom of these supermassive black hole systems in powerful jets that can extend many thousands of light years into space, right out of the galaxies they came from.

These jets have been seen before, but this week’s new image of galaxy M87 includes the black hole and its jet — showing for the first time the direct connection between the two.

The image was produced by an international collaboration using arrays of radio telescopes spread around the world, acting together as one single instrument the size of the Earth. They employed the Global Millimetre VLBI Array (GMVA), which uses of 14 telescopes in Europe, the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA) in Chile, of which Canada is a part, and the Greenland Telescope (GLT).

The scientists hope images such as this will uncover the mechanism behind the energetic jets.

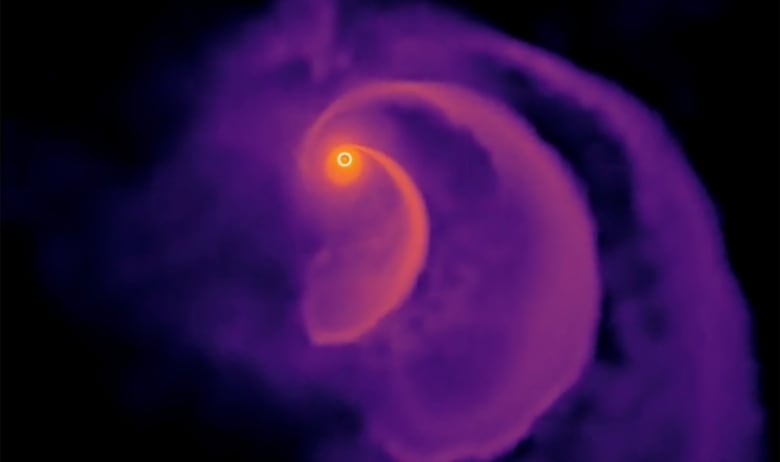

A second team at Northwestern University in Illinois developed a computer simulation to work out what happens when a star passes close to a medium-sized back hole and is not eaten all at once.

The team simulated scenarios in which a passing star is captured by a black hole 100 to 10,000 times the mass of our sun — considerably smaller than Messier 87.

In their simulations, the star falls into a long looping orbit around the black hole. Every time the star gets closer, some of its material is drawn off by the black hole’ gravity. The star loses mass on each orbit until its remnants are tossed away, like a scrap of uneaten food.

Black holes are typically thought of as voracious holes in spacetime that suck in anything that comes near them. But here we have one black hole that spits out jets at almost the speed of light, and another that throws away leftovers.

Black holes are at the limits of our knowledge, where the laws of physics seem to break down and time comes to a standstill.

In his interview with Quirks & Quarks, English physicist Dr. Brian Cox explained how science struggles to understand the inner workings of these bizarre objects, and how solving their mysteries leads to insights into the very fabric of our existence.