Seventy-five million years ago in southern Alberta, a river flooded, burying the eggs of bird-like dinosaurs nesting on the nearby plain. Now, tiny pieces of those fossil egg shells offer new evidence about how dinosaurs lived, bred and evolved into birds.

A new study shows emu-sized, meat-eating troodons were as warm-blooded as birds, with body temperatures of more than 40 C. But unlike modern birds such as chickens that can produce one egg a day, troodons used a very slow egg-forming process similar to the one used by reptiles like crocodiles.

That supports a previous hypothesis that nests found containing up to two dozen eggs were shared by multiple troodons, similar to the way ostriches share communal nests today.

“So essentially, from an eggshell … we were able to get and deduct information about their reproductive system and also their behaviour,” said Mattia Tagliavento, lead author of the study published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

François Therrien, curator of dinosaur paleobiology at the Royal Tyrell Museum in Alberta and co-author of the study, said he was surprised by just how much information could be gleaned from tiny fragments of eggshell no bigger than a fingernail.

How to read an eggshell

Eggshells have previously been used to estimate the body temperatures of some other kinds of dinosaurs, which vary from species to species.

Such estimates rely on the fact that eggshells contain carbonates — minerals made of carbon and oxygen atoms. Heavier forms of carbon and oxygen tend to cluster together more when the temperature is lower. So analyzing the amount of clustering reveals the temperature the eggshells formed in — that is, the dinosaur’s body temperature.

Tagliavento, a postdoctoral researcher at Goethe University Frankfurt, said the technique can be accurate to within plus or minus 4 C.

In the new study, Tagliavento wanted to compare the eggshells of bird-like dinosaurs to modern birds and reptiles. He and his collaborators collected chicken eggs from a local farm, along with turtle and crocodile eggs, mostly from zoos. Knowing the the Royal Tyrell Museum in Alberta had a good collection of Late Cretaceous dinosaur eggs, he reached out to Therrien, who had collected troodon eggs himself in southern Alberta in the early 2000s.

Some had previously been collected in the 1990s by other paleontologists, including Darla Zelenitsky, an associate professor and paleontologist at the University of Calgary.

The nests and eggs were found in an area of Alberta that had a subtropical climate during the Late Cretaceous, but wasn’t as humid or forested as Dinosaur Provincial Park was at the time. Therrien said it would have been more open, with lower-growing vegetation, although grasses hadn’t yet evolved.

Zelenitsky said troodons would have roamed and hunted among birds, turtles, crocodiles, horned and duck-billed dinosaurs, and other small meat-eating bird-like dinosaurs.

Both Therrien and Zelenitsky ended up helping Tagliavento and co-authoring the study.

How birds and reptiles make and lay eggs

Therrien sent Tagliavento a small collection of fingernail-sized troodon eggshell fragments.

When Tagliavento first analyzed the dinosaur, bird and reptile eggshells, he found that they didn’t all follow the same pattern. It turned out that the measurements were affected not just by the temperature at which the eggshells formed, but how quickly.

Birds are very speedy egg producers. While a female has only one ovary, it can produce an egg a day. And within that day, the bird’s body can coat that egg with an eggshell, and lay it in a nest.

In contrast, reptiles have two ovaries, meaning they can produce two eggs at once. But they can’t make eggs as fast as birds. The reptilian process for coating the egg with an eggshell takes a week or two before the egg can be laid.

The researchers managed to correct for those differences by making some changes to their analytical technique.

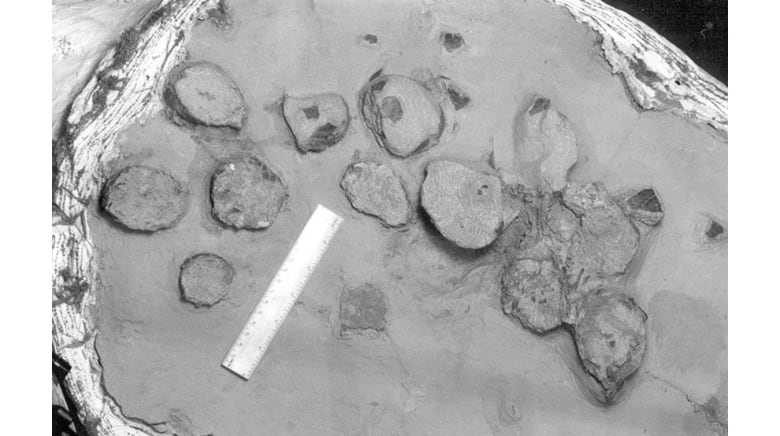

In doing so, they saw that troodons produced eggs slowly like a reptile. Zelenitsky says a troodon female likely produced two eggs per ovary, every week or two. But its eggs were large (about the diameter of a goose egg, but twice as long), and unlike reptiles, researchers don’t think a troodon could accumulate eggs inside its body for weeks.

That means it would likely only lay four to six eggs per season — just a fraction of the two dozen eggs in a given nest.

“Twenty-four eggs of that size looked a bit ambitious for a single individual,” Tagliavento said.

In fact, other researchers had previously proposed that troodons laid their eggs in pairs in communal nests, based on the patterns of the eggs within the nest.

“Now we have some analytical support to say that now yes, probably these troodons were sharing their nest,” Tagliavento said. “Which is a behaviour that now is observed in nature” among some birds such as ostriches.

Therrien said the combination of bird-like and reptile-like traits in such a bird-like dinosaur shows the transition from reptiles to birds was very gradual.

Just how warm-blooded was troodon?

From the eggshell analysis, the researchers were also able to read the body temperature at which the troodon eggs were formed.

Interestingly, they got two different results — some of the eggs formed at 42 C, similar to the body temperature of modern birds and a temperature previously reported for troodon.

But one appears to have formed at 29 C, which has also been reported for both troodon and related dinosaurs. That adds to evidence that troodon may have been able to lower its body temperature like some birds in order to save energy.

In any case, the findings show troodon was warm-blooded and could have sat on its eggs to keep them warm — something researchers had suspected based on other evidence. Zelenitsky said that includes a pair of fossilized troodon legs found atop a nest.

Tagliavento noted that in general, long-extinct animals such as dinosaurs don’t leave behind much more than fossil bones. “They don’t really give access or full access to the original biology.”

He said the eggshell analysis gives them “a window into these dinosaurs’ biology using something that before our work, we didn’t really imagine we could.”