Grape breeding researcher Matthew Clark says he often hears from people who believe one silver lining to climate change is it could be a major boost to cold-climate wine industries like Canada’s.

However, Clark feels this is an overly optimistic thought.

Although winters have become milder on average, the truth is, “We’re going to continue to have extreme weather events. We’re going to continue to have extreme cold,” said the associate professor at the University of Minnesota, where he leads the grape-breeding and enology program.

Clark’s views are in line with other experts interviewed by CBC.

“If you look at the industry in Europe, each year in the last several years, they’ve been nailed with frost, after frost after frost, and that is partly because the vines are waking up too early,” said Jason Londo, an associate professor of fruit crop physiology and climate adaptation at Cornell University based in Ithaca, N.Y.

The winters that climate change is bringing — ones that are milder on average, but still experience drops to extreme cold — could actually be worse for vineyards.

The Great Lakes Climate Change Project is a joint initiative between CBC’s Ontario stations to explore climate change from a provincial lens. You can read more stories from the project here:

But there are other reasons to be optimistic, in the form of new techniques and cold-hardy, disease-resistant grape varieties available now, and even more technologies on the horizon — if the industry and consumers are willing to adapt, say experts.

Canada’s wine landscape is changing

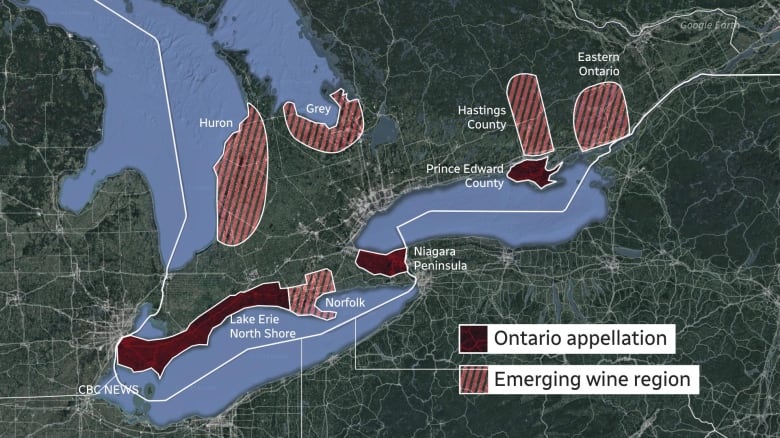

Canada’s wine regions stretch from B.C. to Nova Scotia, including three established appellations in Ontario.

The two southernmost wine regions — Lake Erie North Shore and Niagara Peninsula — have long enjoyed relatively mild temperatures due to their latitude and proximity to the Great Lakes.

This allows them to grow the traditional European grape varietals known as vinifera — from the species name Vitis vinifera — like Chardonnay and Riesling.

“Lake Erie North Shore is our warmest appellation … our oldest wine-growing region. Those guys were winning awards on the international stage in the [1800 and 1900s],” says Beverly Crandon, a certified sommelier based in Toronto.

European varieties like these can be particular and would not survive in most Canadian climates.

When it comes to surviving a changing climate, vinifera varieties have limited options. Since we plant them clonally to preserve the variety, they don’t have a chance to adapt or evolve.

Instead, they acclimate as best they can. When temperatures drop, the vine braces itself for winter, building up cold tolerance and going dormant.

But vines will only prepare as much as they think they need to. A more mild start to the winter means they are less ready for any extreme cold events and more likely to die as a result.

A similar principle applies in the summer.

Heatwaves and unprecedented humidity can be devastating to grape yields and quality, as we’ve seen in B.C. wineries in several recent years. This also brings more diseases and pests.

So even if vinifera biology can do some of the work, technology and innovation need to do the rest.

If the grapes can’t adapt, growers have to

In recent years, many vineyards have had to adopt new strategies and technologies, like geotextile (permeable) blankets to cover vines and wind machines to keep air moving, said Debbie Zimmerman, chief executive officer of Grape Growers Ontario.

“Over the years, we’ve been mitigating what we call winter damage by using wind machines … they’re used on a very limited basis and most particularly when the temperature drops.”

The other option is to change the grapes you’re growing.

Rather than the European varieties that can struggle in our climate to begin with, some growers in places like Nova Scotia have opted for native grape species.

As well, there are hybrid grapes, which are common in Nova Scotia and growing in popularity in Ontario.

Hybrid grapes are created by crossing traditional European vinifera grapes, which provide the taste profile, with native North American grape varieties like Vitis riparia, also called riverbank grapes, which provide cold hardiness and disease resistance.

By slowing the rate at which the grapevine comes out of dormancy in response to warmer temperatures, they become more resistant to late-winter frost events, said Londo at Cornell.

Riparia grapes also have natural resistance to a number of pests that can devastate vinifera vines.

Hybrid hesitation

So what’s the holdup?

“Until main wine regions [like those in Europe] adopt and champion hybrid grapes, I don’t see smaller markets like Ontario doing that,” said Crandon.

She said Ontario’s wine industry has gone all in on traditional varieties and is now resistant to change.

“Ontario is still at the point where we’re trying to show and prove that we can compete on a world scale … and it would be catastrophic if we said, ‘Here’s our wines made from hybrids.'”

Meanwhile, in other provinces like Nova Scotia and countries like Germany, wines from hybrids make up a large portion of the market share thanks to support from governments and consumers.

Crandon said it is unfortunate the same cannot be said here, since she finds many wines made from Ontario’s hybrid varieties are excellent — and some have even won competitions abroad. (You may not know if you’ve had a hybrid variety — in Ontario at least, they are largely listed at the LCBO under the section of international domestic blend, even if they’re made from 100 per cent Ontario grapes.)

Cold-hardy grape varieties — combined with new technologies and warmer temperatures — have also incentivized grape growers in Ontario to expand into new areas.

A new tech that would keep varieties intact

None of the experts CBC spoke with foresee the traditional vinifera varietals disappearing from Ontario vineyards any time soon.

Researchers are exploring ways to improve traditional varieties like Chardonnay without crossing them.

“We could be using these tools to enhance [vinifera grapes] if consumers are resistant to hybrids because they want the name recognition, they want a Chardonnay, they want a Merlot,” said Londo.

One of the most promising tools is something called CRISPR/Cas9.

A precise, quick and simple gene editing tool, the technology earned its discoverers a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020.

The technology changes a specific gene sequence that scientists can easily choose — and Clark says they’re already hard at work identifying candidates through projects like VitisGen3.

CRISPR has myriad potential applications, from curing genetic diseases, to bioenergy, to scientific research.

But it could also help us make crops better adapted to our changing climate — and gene editing avoids some of the issues some people have with traditional genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

This is especially helpful for removing individual genes that make vinifera grapes susceptible to diseases that are becoming a bigger problem because of climate change.

“The advantage from a science point of view is you are changing one thing, the one part of the genome you want to change, instead of in a breeding program when you mix two parents, [and] you’re changing the entire genome,” said Londo.

“So one of the challenges of breeding is not bringing in a bunch of traits that you don’t want in the final product. And CRISPR is seen as a technological way around this.”

The applications are still being explored, but studies indicate it could allow us to make disease-resistant Chardonnay grapes while otherwise leaving the variety completely intact.

So unlike with hybridizing, it’s still 100 per cent Chardonnay.

Applications are also being explored for the yeasts used to ferment grapes into wine, something that could improve both taste and safety — which is top of mind for many consumers in light of the widely-reported recommendations around alcohol recently issued by the Canadian Centre for Substance Use and Addiction.

Londo stressed no one is bringing CRISPR grapes to market any time soon. You won’t find CRISPR wine at the liquor store for years, if ever. It all comes down to what people will buy.

But those in the industry seem eager to try.

“Of course we would use those [CRISPR] grapes, if it meets those taste and quality requirements. We’re always looking at new technologies,” said Zimmerman.

As a sommelier, Crandon was able to sum up her feelings quite easily.

“I would drink the wine.”