Newfoundland and Labrador is a world leader in trying to save whales tangled in ocean detritus, including fishing gear, communications lines and plane debris.

Now the province’s whale-disentanglement experts are working to pass those skills on to others.

“Different groups use different tools, so we’re looking at the safest and most effective,” said Julie Huntington of the St. John’s-based group Whale Release and Strandings.

“We’re discussing adapting tools and have prototypes that have never been in the water. This workshop is one of the first of its kind, and we will all walk away with new ideas.”

The group recently hosted a whale disentanglement workshop at the Marine Institute in St. John’s — a chance for people from New Brunswick’s Campobello Island, the Quebec Maritime Mammal Response Network, and British Columbia to discuss tools and techniques for freeing whales from fishing gear.

“Our tools were originally developed through the Whale Research Group and Jon Lien, but the fishing gear has changed as time passed,” said Huntington. “We often don’t know who the gear belongs to, so we work to get it off the whale and out of the water.”

The workshop happened alongside the world’s biggest flume tank — a 1.7-million-litre tank used to test gear and techniques, among other things.

The practice of disentangling whales began in Newfoundland and Labrador in 1979 — to try to retrieve fishing gear and return it to fishermen.

Huntington and her colleague Wayne Ledwell learned about whale disentanglement from Jon Lien, an animal behaviourist and organic farmer nicknamed “the whale man.”

Lien founded the Newfoundland Whale Research Group and pioneered and innovated many whale rescue techniques now used worldwide.

“At one point, we were cautious about cutting nets and wanted to return gear to fishers so they could return to fishing immediately,” said Huntington, who started working with the group in the late ’80s.

But the tools they use and their priorities have changed since then, she said.

These days, Huntington and Ledwell use a five-metre Zodiac, and alongside a safety boat they use a variety of cutting tools to free tangled whales.

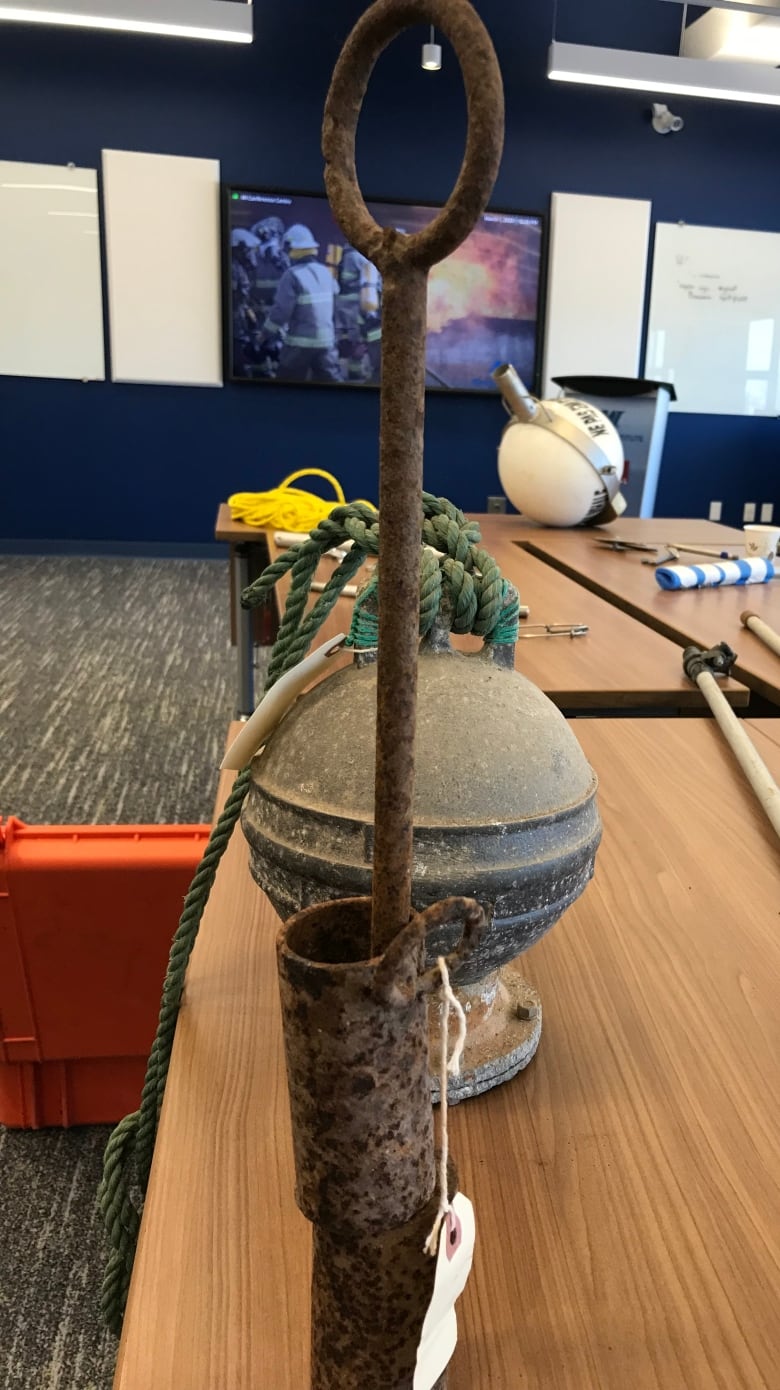

She points to a rusty piece of machinery on a table.

“That’s a clanger. We no longer use them, but they would be attached to a buoy near a cod trap. The idea is that it would — hopefully — make a unique noise and let the whale know that there was danger ahead.”

Patience and care

Imagine trying to untangle a herd of seven charging elephants — while they’re moving.

Now try to do that while navigating on the ocean, and you start to get a sense of what people trying to disentangle whales are dealing with.

“These are 40-50-tonne animals. They are agitated and distressed. You must be very careful and patient and not move in too quickly. When an animal nears exhaustion, making those cuts gets a little safer,” said Paul Cottrell, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ marine animal co-ordinator in British Columbia.

Cottrell, one of the experts at the workshop, leads whale rescues along the vast British Columbia coastline.

In 2021, there were 34 reported large whale entanglements in British Columbia, with similar numbers last year.

While summer is the busy season, Cottrell and his team rescued a humpback just last month.

“The biggest challenge for us, in British Columbia, is the hugeness of the coastline. We train people along the coast to attach satellite buoys with satellite tags to whales,” he said.

The tags help speed things up for Cottrell, who can lose valuable time trying to track down an entangled whale.

“By having these tags attached, we can find the whale. Then we grab the right gear, wait for the right weather, and most importantly, be in the right place,” he said.

If a whale is moving and the team can’t locate it, then each satellite buoy has a timed release, which means the team won’t be adding more drag to an already entangled whale.

Cottrell’s team has two vessels: the rescue vessel and a support vessel for safety.

He also uses drones to help identify gear configuration.

“They enable us to assess if the whale is entangled around the mouth, the tail stalk,” he said. “This is information we absolutely need.”

Whale rescue in the Bay of Fundy

Mackie Green used to be a lobster fisherman.

He’s tried out most types of fishing and comes from a long line of fishers.

“Most of our team worked in the industry, and we have a close relationship with the fisherman in our area. They’ll come to help us with a disentanglement,” he said.

Green’s been the director of whale rescue with the Canadian Whale Institute on Campebello Island for the last five years. His team works with the occasional minke or fin whale, but they mostly disentangle humpbacks and endangered northern right whales.

“Right whales seem to be the hardest to work with. They are just incredibly robust, and they don’t tire out. They migrate, constantly moving,” he said.

The summer habitat of the right whale has shifted north, so the team from Campebello Island work out of a larger Zodiac than the team in Newfoundland.

“We’re often 40 or 50 miles offshore,” he said. “We need a bigger boat. We use satellite tags too, and we just started using drones. They help us because we can see overtop without spooking the whales.”

What are the two biggest problems for whale rescue work in the Bay of Fundy?

“Well, we do not hear from fishers as much as we should. There’s a lot of fear about having the fishery shut down, so whale entanglements go unreported, but an entangled humpback will not shut down an industry, so we need those calls. Call us,” he said.

Green is also concerned about people who try to help without the proper training or certification.

“Folks will see a whale dragging a rope, and they’ll shorten a rope,” he said. “We need that rope. We aim to free the whale completely but often need to latch on to rope to untangle it. It’s very frustrating because well-meaning people can doom a whale,” he said.

The opportunity to debate, discuss and learn has been valuable for all the teams, said Green.

“Newfoundland is where so many of our techniques were pioneered, so this workshop has been an incredible opportunity,” he said.

Read more from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador