WASHINGTON — Last week, TikTok’s chief executive, Shou Zi Chew, met with several influential think tanks and public interest groups in Washington, sharing details on how his company plans to prevent data on American users from ever leaving the United States. And the company’s lobbyists swarmed the offices of lawmakers who have introduced bills to ban the app, telling them that TikTok can be trusted to protect the information.

TikTok, the popular Chinese-owned video app, has been in the cross-hairs of American regulators for years now, with both the Trump and Biden administrations weighing how to ensure that information about Americans who use the service doesn’t land in the hands of Beijing officials.

Through it all, the company has maintained a low profile in Washington, keeping its confidential interactions with government officials under wraps and eschewing more typical lobbying tactics.

But as talks with the Biden administration drag on, pressure on the company has arrived in waves from elsewhere. Congress, state lawmakers, college campuses and cities have adopted or considered rules to outlaw the app.

Now, TikTok is upending its strategy for how to deal with U.S. officials. The new game plan: Step out of the shadows.

“We have shifted our approach,” said Erich Andersen, general counsel of ByteDance, the Chinese owner of TikTok. He said that the company had been “heads down” in private conversations with a committee led by the Biden administration to review foreign investments in businesses in the United States, but that then the government put the negotiations “on pause.”

“What we learned, unfortunately the hard way, this fall was it was necessary for us to accelerate our own explanation of what we were prepared to do and the level of commitments on the national security process,” Mr. Andersen said.

TikTok is at the center of a geopolitical and economic battle between the United States and China over tech leadership and national security. The outcome of TikTok’s negotiations with the U.S. government could have broad implications for technology and internet companies, shaping how freely digital data flows between countries.

For two years, TikTok has been in confidential talks with the administration’s review panel, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, or CFIUS, to address questions about ByteDance’s relationship with the Chinese government and whether that link could put the sensitive data of 100 million U.S. users into the hands of Beijing officials. The company assumed that those talks would reach a resolution soon after it submitted a 90-page proposal to the administration in August.

Under the proposal, called Project Texas, TikTok would remain owned by ByteDance. But it would take a number of steps that it said would prevent the Chinese government from having access to data on U.S. users and offer the U.S. government oversight of the platform. Some of those steps have been put in place since October.

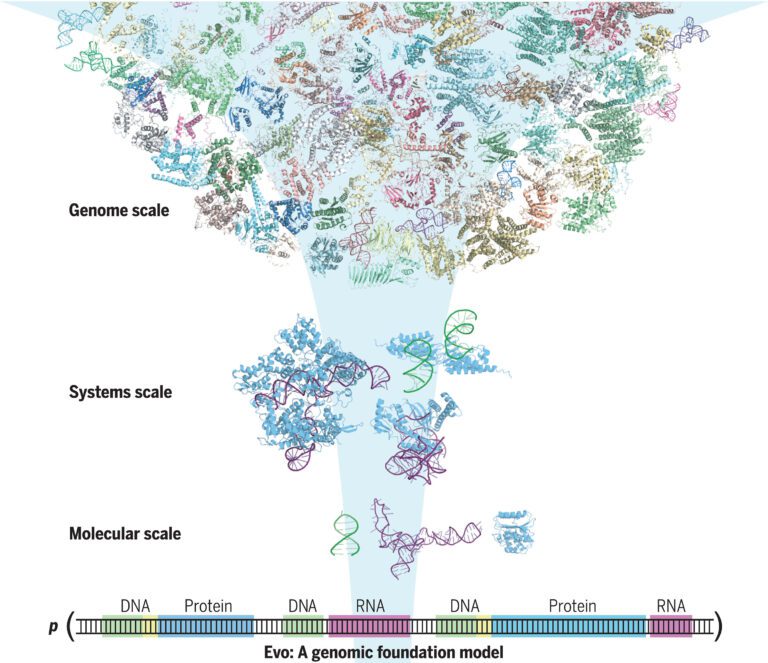

The company has proposed putting all U.S. user data into domestic servers owned and operated by Oracle, the American software giant. The data would not be allowed to be transferred outside the United States, nor would it be accessible to ByteDance or TikTok employees outside the country.

The program proposes having CFIUS conduct regular audits of the new data system and creating a new unit, TikTok U.S. Data Security, with 2,500 engineers, security experts, and trust and safety officials, all based in the United States, who have access to TikTok’s U.S. user data for business functions. The unit would report to a three-member board assigned by CFIUS. In addition, TikTok’s source code, which offers insight into why certain videos are shown in users’ feeds, would be reviewed by Oracle and a third-party inspector.

Some details of the proposal were reported earlier by The Wall Street Journal.

“We knew that, in order to earn trust, we would have to build a system that provided an unprecedented level of security and transparency — that’s what we’ve done and will continue to do,” Mr. Chew said in an interview.

The proposal, though, has yielded little response from the panel, Mr. Andersen said. TikTok said it had asked about the status of the panel’s review in numerous emails and received little response. The company’s officials learn about the administration’s thinking on the proposal only through news coverage, they said.

In a statement, a spokeswoman for the Treasury Department, the lead agency of CFIUS, said the panel was “committed to taking all necessary actions within its authority to safeguard U.S. national security.” She declined to comment about TikTok’s depiction of the negotiations, saying the panel doesn’t comment on cases it may or may not be reviewing.

TikTok’s more aggressive lobbying stance will not necessarily yield different results. The company has few allies in Washington. The most powerful tech lobbying groups, like the Chamber of Progress and TechNet, prefer to represent American companies and have policies against representing Chinese companies. In fact, many big tech companies, like Meta, have argued that TikTok poses a security threat.

And lawmakers in both parties have expressed concern. Senator Mark Warner, a Democrat from Virginia and the chairman of the Intelligence Committee, has said that the company has misrepresented how it protects U.S. data from Chinese-based employees, and that he is considering a bill to outlaw the app in the United States.

On Tuesday, Senator Josh Hawley, a Missouri Republican, introduced a bill to ban the app for all American users after successfully passing a bill in December that banned the app on all devices issued by the federal government.

“A halfway solution is no solution at all,” said Mr. Hawley, who is among a growing number of lawmakers who don’t see a compromise on data storage and access as a solution to TikTok’s security risks.

Yet the growing pressure on the company has left it few options other than changing its approach, many outside experts say.

“The issue has become public in a way that they can’t ignore,” said Graham Webster, the editor in chief of the DigiChina Project at the Stanford University Cyber Policy Center. “And this may be their way of pushing to actually get the CFIUS agreement completed, which is really their best chance of a sustainable business path in the United States.”

In a 24-hour visit to Washington last week, Mr. Chew held four back-to-back 90-minute meetings with think tanks like New America, academics and public interest groups such as Public Knowledge. In the company’s temporary WeWork suites near Capitol Hill, Mr. Chew and Mr. Andersen outlined the promises in Project Texas in a presentation with graphics on how the data is stored in Oracle’s cloud and TikTok’s appointment of a content moderation board and auditors.

They told the groups that the company rebuked allegations that China interferes in the business, but that they had built the system to prove their commitment to security, according to people at the meetings.

“It seemed like a serious effort,” said Matt Perault, the director of the Center on Technology Policy at the University of North Carolina, who attended a briefing and whose center receives funding from TikTok.

He added that the company appeared to be trying to shift the discussion about it from hypothetical risks to operational and technical solutions. TikTok would spend $1.5 billion to set up its proposed plan and then as much as $1 billion a year. U.S. users may have a slightly worse experience with the app outside the country, a cost of operating from Oracle’s servers, the company executives said.

Mr. Perault said even with those efforts, “they can’t make something zero risk.”

“There is no way they can guarantee data won’t go to an adversary in some way,” he said.

As part of its more aggressive public relations offensive, TikTok has invited journalists to Los Angeles this month for a first-time tour of what it calls its “transparency and accountability center,” a physical space where it shows how humans and technology moderate videos on the platform.

In recent days, TikTok and ByteDance have posted half a dozen communications and policy job openings in Washington. The new jobs would add to the 40 lobbyists whom the companies now have on contract or as employees. Those lobbyists include four former members of Congress, such as Trent Lott, the former Republican Senate majority leader, and John Breaux, a former Democratic senator from Louisiana. The companies have also recently posted job openings for roles doing strategic communications and policy for engagement with state and federal officials.

ByteDance spent $4.2 million in federal lobbying in the first three quarters of 2022 and is expected to far outpace that figure this year.

A spokeswoman for TikTok said the company’s lobbyists had a hard time scheduling meetings with lawmakers who were critical of the company in TV appearances.

Representatives Mike Gallagher, a Wisconsin Republican, and Raja Krishnamoorthi, an Illinois Democrat, who are co-sponsors of the bill in Congress to ban TikTok, said they planned to meet with the company soon.

But Mr. Krishnamoorthi made it clear that he would not be easily persuaded to change his position. He said in an interview that TikTok was “taking a more aggressive stance in Washington,” but that the company had yet to meaningfully address some of his concerns, such as how it would respond to a Chinese media law that allowed the government to secretly demand data from Chinese companies and citizens.

Mr. Gallagher said he wanted more information from CFIUS about ByteDance’s proposed ownership structure. “I come in somewhat skeptical — I prefer a ban or a forced sale, but I’m more than willing to do my due diligence in examining the technical aspects of such an arrangement,” he said. And even then, he said, “where we have a lot of unanswered questions” is around how its recommendation system works.

Mr. Gallagher said new questions kept popping up as well. He pointed to reports about ByteDance tracking journalists, and Michael Beckerman, TikTok’s head of public policy for the Americas, struggling in a recent CNN interview to answer questions about China’s treatment of Uyghurs, a Muslim minority in the Chinese region of Xinjiang.

“What we’ve seen is a steady drip of negative information that calls into question what they’ve said publicly,” Mr. Gallagher said. “When I see things like that, what am I left to conclude other than ByteDance and TikTok are afraid of offending their overlords in Beijing? It does not reassure people like me.”