In 2015, players of the video game Dwarf Fortress – a wildly influential cult hit that has appeared at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and been cited as the inspiration for Minecraft – started finding vomit-covered dead cats in taverns. When the game’s creator, 44-year-old Tarn Adams, attempted to determine the cause, he discovered that cats were walking through puddles of spilled alcohol, licking themselves clean, and promptly dying of heart failure due to a minor error in the game’s code, which overestimated the amount of alcohol ingested.

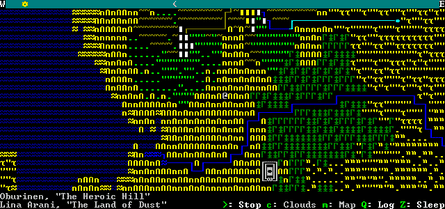

Most games don’t simulate anything nearly as complex as alcohol poisoning and feline grooming, but Dwarf Fortress does, and the way that its code generates these bizarre situations is symbolic of what people love about it. Dwarf Fortress has a unique, incredibly complicated approach to storytelling and play, but it looks like pure Matrix code, composed entirely of coloured text. Any casual observer would find it indecipherable.

That is, until now. The game’s upcoming commercial release, after 20 years of ongoing development, will add pixel graphics, music, and a host of other things to make it more palatable. “Every single screen has been redone,” says Tarn. “It’s a big improvement.”

Dwarf Fortress is most easily described as a strategy game where you direct, as the name implies, a fortress of dwarves. There aren’t any explicit goals, and the only true certainty of the game is this: at some point, your colony will fall. Perhaps you’ll get greedy and delve too deep and too quickly into the bowels of the earth; perhaps you awaken the fury of cannibal elves by cutting down too many trees. Maybe your settlement will be laid low by a dwarven tantrum spiral.

What makes the game special – besides its stark presentation – is the ridiculously detailed extent to which the world is simulated. Cat vomit is barely the starting point. The game generates epochs of history, complete with casts of individual heroes and villains; it keeps track of hundreds of characters’ individual body parts, desires, emotions and moods, and makes a spirited attempt to emulate physics.

All of it, up until quite recently, has been the product of just two people: Tarn and his brother Zach, who have been working on Dwarf Fortress for almost two decades. The brothers, based in the US, have historically released a new version for free whenever they had one ready to go. But in 2019, a health scare inspired a shift in priorities.

“I had to go to the hospital for skin cancer,” says Zach. The treatment cost him $10,000, which his insurance – obtained through his wife’s company – mostly covered. But it got them thinking about what could have happened if Tarn, who describes his current health insurance as “crap”, had been diagnosed with something major instead.

Between donations from fans and a small-scale Patreon following, Tarn and Zach were eking out a living from Dwarf Fortress, but both knew the costs of operations and ongoing healthcare in America could easily bankrupt them.

“It’s not an ideal setup, right?” says Tarn. “It’s just not tenable, especially as you age. You’re not just going to run GoFundMes until you can’t and then die when you’re 50. That is not cool.”

The pair decided to team up with a Canadian publisher, Kitfox Games, and announced a “premium” version of the game, hoping to attract more fans and secure more sustainable revenue. So far, they say, things look like they’re going “really well”.

The brothers note that the classic version will still be available for free, with updates matched to the paid edition; the premium game’s various additions are mostly about making it more approachable, rather than drastically changing the underlying game. Other than better visuals and a new soundtrack, the commercial release also features mouse controls, a completely redesigned interface and proper in-game tutorials to help you find your way around. Zach’s wife, whose previous game-playing experience begins and ends at The Sims, served as the primary tester.

“It’s funny how we have an aesthetic even though we’re a text game,” says Tarn, who says the team’s artists took their time finding an art style that was more readable than stark ASCII characters but still left “room for interpretation”. The two say they originally stuck with text because not having to think about graphics greatly sped up development – but even with a greater emphasis on the visuals, they are adamant that the core of Dwarf Fortress is in the emergent narratives the game creates with all its maths and simulations.

“The whole project began with us writing short stories,” says Zach. “The stories aren’t very special. We aren’t good writers. But we wanted these wacky things [to be able to happen] in the game.”

Tarn describes their aim as creating a “story engine”, and they’re still trying to figure out the best way to explain it. Every feature in the game, he says, has to be interesting to simulate AND have an interesting effect that players can notice. At one point they added mannerisms, where nervous dwarves might tap their feet – but dwarves being nervous didn’t actually affect the rest of the game, and therefore it wasn’t obvious to players. “If you make the simulation really complicated, but you don’t surface it to the players,” says Zach, “it’s not going to become part of their story.”

Sometimes the simulation throws up interesting errors (though none have been more entertaining than the legendary drunken cat bug). At one point, wandering groups of outcast poets or scholars would turn up stark naked because, as Tarn explains, having being expelled from civilisation, the simulation determined that they no longer had any clothing requirements, and had thus decided to go au naturel.

Tarn and Zach agree that the commercial release is the “start of a new era” with the game, which is nowhere near complete in their eyes, even after 20 years. Tarn wants to implement armies and sieges: “right now you can lock up your fortress and you’re safe … that era will come to an end in a few years.” Simulated myths and magic are also on the table.

“We have more plans after that, of course,” says Tarn, “but they’re not in order. We’ll have to see what makes sense to do, because now we have other people to think about,”

“It just keeps going,” laughs Zach, after a slight pause. “For ever and ever.”