Richard and Kathy Verlander promised their son a sports car if he earned a college scholarship. So, in the fall of 2002, a gangly goofball from Goochland, Va., drove onto the campus at Old Dominion University in a black Mustang.

Three months earlier, the Pittsburgh Pirates pondered picking Justin Verlander in the Major League Baseball draft. The family had set a $500,000 asking price to pry Verlander away from a college commitment. Pittsburgh passed.

Across 49 rounds and 1,481 other picks, 29 other clubs did, too. Strep throat had sapped some of Verlander’s velocity to start his senior season at Goochland High, scaring away scouts and perhaps some of the more prestigious college programs.

“But by the end of the year, my velo was back up — just nobody was there to see it,” Verlander said. “Except Old Dominion.”

Players with Verlander’s promise don’t often pick places like Old Dominion. The team finished 19-37 a season before Verlander arrived, and had produced eight major-league players since 1965. Verlander believed he would be the ninth.

“When he first rolled up to campus, I’ll be honest with you, he was a little cocky,” said Evan Chipman, the classmate who caught every start of Verlander’s junior season. “He didn’t get a very welcome reception when he first got there.”

“I mean, he rolled up in a black Mustang with the license plate saying JV BRINGING IT 94.”

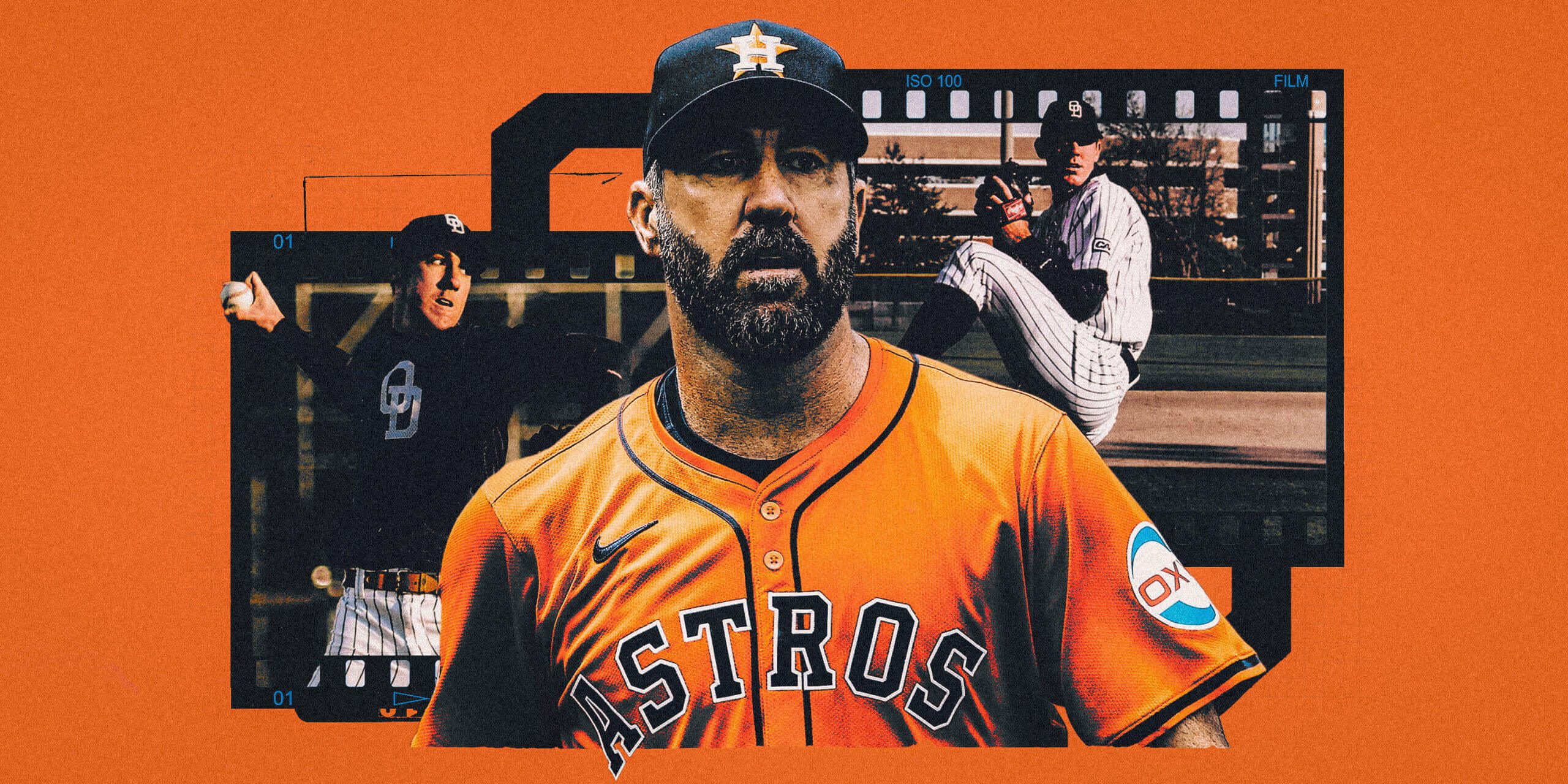

But bravado works best when backed up. Verlander has done that, and will continue Wednesday when he returns from the Injured List. Cooperstown will come calling whenever the Houston Astros’ ageless ace concludes a career that catalyzed in college — inside a tiny ballpark called The Bud, on the banks of the Elizabeth River, and within a three-story townhouse on West 48th St. in Norfolk, Va.

“I had nothing to prove, man,” Verlander said. “I had an inkling that I had talent and I wanted to see where that took me. It wasn’t until college that I learned how good I was.”

Two decades later, those who were there call it their claim to fame: witnessing the formative years of a future Hall of Famer.

“He had the ability to be likable while he was kicking your ass, if that makes any sense,” said Shohn Doty, his first collegiate pitching coach. “Our guys respected his work ethic. It was nice to have that guy and have that confidence and that arrogance.”

Finding the balance between the two is difficult. Verlander possessed natural talent few players then or now could fathom. Flouting it felt natural, but furthering it was his main goal.

Within two months on campus, Verlander usurped upperclassmen for a Friday night starter’s role he never relinquished. He touched 97 mph in his first collegiate start, surprising scouts and even himself. Verlander’s 427 strikeouts remain the most in both Old Dominion and Colonial Athletic Association history.

“I remember him saying, ‘What I’m going to be is, I’m going to be a professional baseball player, but I’m going to be in the Hall of Fame,’” said Jesse Schoendienst, one of Verlander’s classmates and roommates.

Verlander’s starts became appointment viewing. In a ballpark that had sometimes seated just 60 fans, crowds swelled, there to see the heat that Verlander’s sports car promised. He would’ve preferred a Mustang with the v8 engine, but settled for the v6 with a vanity plate that still prompts teasing from former teammates.

“B-R-N-G-N-I-T,” Verlander recalled, raising a finger while reciting each letter, and laughing at his teammates’ claims it included a number. “I even drove it to my first big league camp. You can imagine how that went.

“But, I was bringing it, so I was like ‘f— it.”

It rained on the first day of fall practice in 2002, something Brent Sollenberger shouldn’t remember, but Verlander made impossible to forget. The lanky freshman introduced himself while Sollenberger, a junior captain, played catch with classmate John Oehler down the left field line.

Oehler asked the rookie whether he was any good. Verlander told both teammates they’d soon find out. A waterlogged baseball sat nearby. The upperclassmen wondered whether the freshman could throw it out of the stadium. Verlander could.

“We’re both kind of jaws dropped, but he was a freshman, we couldn’t let him know that he impressed us,” Sollenberger said. “Basically give him a little ‘Nice throw, rookie.’”

“From that day forward, you knew there was something a little different about the guy.”

Verlander arrived on Old Dominion’s campus as “a long, gangly dude with these long arms, but running back legs and massive core strength,” Schoendienst said.

“Probably 160 pounds soaking wet,” throwing partner and fellow pitcher James Burok said. “The coaches always said, ‘James, you’re going to run with Justin. Justin, you’re going to eat with James.’”

Verlander was not quite unheralded, but he did not emerge as a premier prospect until late in his high school career. Coaches who recruited him saw projectability, but a fastball that hovered around 86-87 mph.

“You kind of circled the name, sent him a letter and a questionnaire,” said Terry Rooney, Old Dominion’s recruiting coordinator. At that time, colleges almost never pursued high school players until they began their senior season. Old Dominion offered Verlander prior to his junior year. Longtime head coach Tony Guzzo, a gregarious man with heavy hands and a no-nonsense attitude, bonded with Verlander and his family.

Verlander committed in July, on one of the earliest dates allowed by the calendar. Rooney and Guzzo still didn’t relent, continuing their pursuit as Verlander’s velocity increased and began to attract more attention. The two men made him a top priority, even showing up at one of Verlander’s high school basketball games.

“I did know that we were going to have to get him early in the process to get him,” Rooney said. “That was just the business side of it. I knew that if this thing went on, the UVAs, the Clemsons, the Virginia Techs, those kind of people might take a shot on him.”

None of them did, but seven-time national champion LSU inquired during Verlander’s senior year, he said. Duke, too. Redshirting or pitching out of the bullpen were distinct possibilities at both bigger programs. Verlander declined their overtures.

“Once I make a decision, I usually try to stick with it and see it out. It ended up being the best thing for me,” Verlander said.

“I think back on that, honestly, quite a bit. What would have happened if I’d gone somewhere else and not had that opportunity to be the guy right away? Who knows. Maybe I would’ve been anyway. I’d like to think that a generational type-talent would’ve found his way.”

In 2019, Verlander became just the sixth pitcher to throw three no-hitters, and would go on to win his second of three Cy Young awards. (Fred Thornhill / The Canadian Press via AP)

They called a three-story townhouse on West 48th St. the “baseball house.” Six players and at least one dog called it home. Most who lived there marvel that they made it through two years unscathed. Some wonder how the house is still standing.

“I think it’s burned down three times,” Chipman said. “That house was decrepit. It was really bad. Just a college, nasty house.”

Verlander, Chipman, Burok and Schoendienst all moved in before their sophomore seasons. Verlander’s dog, Riley, became one of the house pets. Verlander would purchase $5 dishes at Goodwill when the house ran short; washing the ones already in the sink seemed too tall a task.

Verlander’s silliness grew on all of his housemates, who still watch him from afar — the roommate who once refused to do dishes, now one of this generation’s greatest pitchers.

“I mean this in a good way, but when I see him being interviewed and how eloquent he is and how thoughtful he is and how professional he is, it’s really cool to see — not saying he wasn’t eloquent and professional or anything like that — but he had his quirks and was goofy,” Burok said.

“Back then Natural Light cost $8,” said Schoendienst, who had the house’s lone fake ID. “He’d give me, like, $8.10. I’d go get it and come back and he’d be like ‘Where’s my change?’ I’d be like ‘Dude, it’s nine cents change.’ And he’d be like, ‘Yeah, I want my change.’ Like adamant.”

Frugalness is the first quirk many of Verlander’s former teammates bring up. Now that he’s made more than $370 million, most believe Verlander has likely grown out of it.

Verlander mastered a Waldo costume that earned acclaim at campus Halloween parties. He became known for riding his bike around campus for hours. Once, after a night of indulgence by Verlander, Schoendiest saw a police officer threaten him with a charge of biking while intoxicated.

To avoid it, Verlander straddled the bicycle and walked it back to the dormitory. He picked leaves off trees along the way, telling teammates, “look, I’m a giraffe.”

“I think he knew he was dorky and just kind of embraced it,” Chipman said. “He’s just goofy. He was kind of like a kid that hadn’t been let out in a while.”

The house hosted a plethora of parties. Indoor golf became a house tradition on nights off — sometimes with actual golf balls that blasted through drywall. A miracle shot Verlander still remembers caromed off a keg and into a waiting solo cup.

The roommates stayed together for two years, and the house witnessed its share of testosterone-fueled scraps over small things, be it unattended dog droppings, dishes piled up in the sink or the assorted stresses college can bring. Animus never lingered for more than a few minutes, but one instance still lives in college lore.

Chipman, Verlander’s catcher, scrapped with his pitcher over some now-forgotten house issue.

“My claim to fame,” Chipman said. “I’ve punched that guy in the face.”

Verlander’s Old Dominion debut attracted a slew of scouts to watch Larry Broadway, who the Montreal Expos would select in the third round of that June’s draft. He batted near the top of a Duke lineup facing a wide-eyed freshman pitching a season-opener.

When he arrived at Old Dominion, Verlander averaged 91 mph and could touch 93. Strengthening his core and staying in his lower half became a priority.

“His work ethic was through the roof,” Doty said. “He took off in the weight room, took off in conditioning and arm care. He tried to win every day, whether it was winning by throwing a pen, in the weight room, on sprint day.”

Sixty-six of Doty’s pupils have been drafted across a 34-year coaching career that spans seven schools. None possessed the talent Verlander brought to Old Dominion. Doty’s mission became harnessing it. Slowing Verlander down is impossible, but Doty needed to dial in his focus.

“He was searching for perfection in an imperfect game,” Doty said. “He finally figured out the idea of just staying within yourself because his stuff was so, so good it didn’t have to be on the black. If he could command both thirds of the plate and stay out of the middle, guys weren’t going to hit him anyway.”

Verlander only finished four innings against Broadway’s Duke Blue Devils. They played before the days of TrackMan, so Richard Verlander always sat above the scout seats to read their radar guns. What he saw stunned both father and son: 97 mph, a velocity Verlander maintained throughout the game. To that point, Verlander said he’d never thrown harder than 93.

“I still get chill bumps thinking about it,” Verlander said. “That was the first time I was like, ‘Holy s—, I don’t see guys at the major-league level doing that.’ The talent is there: just hone it.”

Verlander finished his freshman season with a 1.91 ERA. He struck out 137 batters across 113 2/3 innings.

A team rule permitted pitchers to take pregame batting practice after throwing a shutout. Toward the end of his freshman season, Verlander threw another one and got to show off.

Old Dominion used Nike bats with caps on the end that popped off. Verlander grabbed a bat and filled it with tennis balls. The brash freshman who spent much of the season bragging to teammates about his power corked a bat to crush balls even farther.

Afterward, Verlander put the illegal bat in the wrong rack. Sollenberger, the team’s unquestioned leader, grabbed it during the game. He drilled a double, but didn’t see the tennis balls fly out of the bat and onto the field.

An umpire soon informed him — while calling him out at second base.

“My parents are in the stands. My grandmother’s in the stands,” Sollenberger said. “I can sit back and laugh at it now, but at the time I wasn’t as lighthearted about it.”

The league did not suspend Sollenberger, and umpires allowed him to remain in the game. Still, both he and Guzzo steamed inside the Old Dominion dugout. A culprit came forward after a few minutes of hard lectures.

“Verlander literally has to raise his hand and be like, ‘I did it coach, that was me,’” Schoendienst said.

Sollenberger harbors no ill will now. His son is 15 and watches Verlander with great interest. Every now and then, his dad will detail their college years.

Chipman’s wife can hardly meet anyone without bringing up her husband’s batterymate. During Verlander’s early years in Detroit, he flew Chipman and his father down to Baltimore for a game he pitched. Chipman’s father died a few months later — and it remains one of their most meaningful moments in his final months.

“My dad was one of those ones that sat in the stands and watched him grow up,” Chipman said.

Verlander has fallen out of touch with most of his Old Dominion teammates, but they still remember him fondly. Verlander has risen to another level, evolving from the freshman eager to show an entire school he could bring it.

“When you have somebody that works like that, on top of the God-given natural talent that he has, there’s no envy of the success,” said Burok, an eighth-round pick of the Colorado Rockies.

“I played with guys in the minor leagues who had all of that God-given talent and didn’t work. And for Justin to recognize how good he was and to work as hard as he did, that’s a testament to him.”

To start his sophomore year, he faced Vanderbilt’s Jeremy Sowers, a southpaw who stood atop almost all major-league draft boards. An army of evaluators surrounded Sowers during his pregame bullpen session. Across the field, Verlander warmed up alone and wondered why.

“Well, he’s probably going to be a first-rounder or second-rounder,’” Doty answered.

Verlander struck out 12 and threw a complete game shutout. Legendary Commodores coach Tim Corbin called the performance “as good as you will see at the college level.”

“I remember going home and calling my then-wife and saying, ‘I think I may be coaching a Hall of Famer here,’” Doty said.

(Top image: Eamonn Dalton / The Athletic; Photos: Ronald Martinez / Getty Images; Courtesy of ODU Athletics)