The success of the Matildas at the FIFA Women’s World Cup has women’s football riding a wave of momentum most sports could only dream of – male or female.

The likes of Kerr, Fowler, Carpenter, and Catley are all household names with arguably more recognition than any Socceroo. Yet the divide between men’s and women’s football remains a burden behind the scenes.

Elise Kellond-Knight knows it all too well. She made her debut for Australia in 2007 and brought up her 115th cap last year. She missed the 2023 World Cup at home after rupturing her anterior cruciate ligament. That was her second ACL tear.

Watch the 2024 UEFA Champions League final between Real Madrid and Borussia Dortmund on June 2 AEST, streaming ad free and live on Stan Sport

Both times she blew her knee out she was on her period. The first she puts down to bad motor mechanics, trying to pivot too quickly. The second was when she was shoved in the back and planted heavily. She believes menstruation predisposed her to the injuries.

Katrina Gorry of the Matildas celebrates with her teammates Sam Kerr and Elise Kellond-Knight of the Matildas after scoring a goal during the Women’s Olympic Football Tournament Qualifier match in 2020. Mark Kolbe via Getty Images

A sudden change of direction, twisting, and landing heavily are often when the ACL lets go. The recovery time from the injury is at least nine months.

A 2016 study found female footballers were 2.8 times more likely to suffer an ACL tear than their male counterparts.

READ MORE: ‘I’m not happy’: ‘Frustrated’ Ricciardo’s blunt admission

READ MORE: ‘Rarely gets a headline’: Most underrated NRL players

READ MORE: Foxx optimistic about injury forced withdrawal

There are various theories as to why that may be. The aforementioned study claimed there was no consensus in the scientific community that sex hormones play a part in an increased incidence of ACL injury in women.

However, Kellond-Knight said the trend among athletes she’s spoken to is that more often than not they injure their knee mid-cycle.

Elise Kellond-Knight speaks to the media during a Matildas media opportunity in 2023. Quinn Rooney via Getty Images

She says it’s not something that’s often spoken about between players and their respective clubs, but the increase in incidence over the past 18 months alone has pushed clubs to start taking the theory seriously.

“I think hormones are probably one of the biggest research areas that might reveal something,” she told Wide World of Sports.

“I’ve had two ACL injuries. The moment of your cycle where your hormones are at, for me personally, was the same moment (of injury).

“The amount of ACLs when a girl is on her period is enormous. There has to be something hormonal going on there.

“They’re tracking the girls’ cycles. They’re doing research at their club level. It’s fascinating.

“When your hormones are at a certain level they affect your strength. Hormones directly relate to women’s strength. How do we do more research into that?

“After doing two ACLs at that time of my cycle, I’m hyper-aware if it is that time if I go into a game – high risk. Maybe you do take a little bit more caution. After two injuries you don’t want any more.

“It’s not spoken about. It’s under-researched. As players, we know. Anyone with an ACL (injury) we always ask ‘Were you on your period?'”

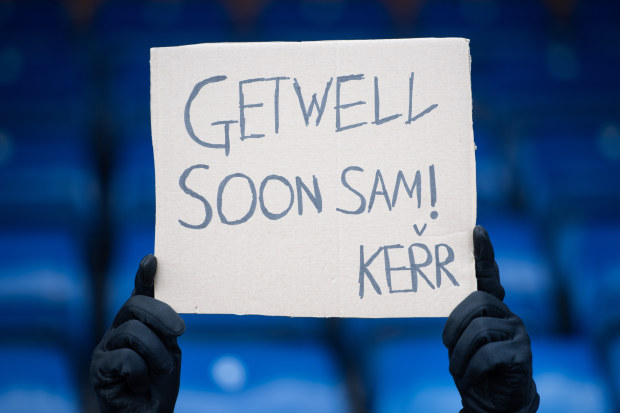

A fan holds up a banner wishing Sam Kerr to get well soon following her ACL injury. Visionhaus/Getty Images

Women’s football globally has had something of an ACL epidemic. Sam Kerr was among a throng of world class players to suffer an ACL injury last year and she’ll miss the Paris Olympics as a result.

A Sky Sports investigation earlier this year found 195 women had suffered an ACL injury over the 18 months prior.

High-profile players Leah Williamson and Beth Mead (England), Janine Beckie (Canada), Delphine Cascarino and Marie-Antoinette Katoto (France), Vivianne Miedema (Netherlands), Christen Press and Catarina Macario (United States) all missed the World Cup.

Such is the seriousness of the issue that UEFA commissioned an expert panel on women’s health in 2023 to better understand the problem.

Beth Mead of Arsenal receives medical treatment during the FA Women’s Super League match between Arsenal and Manchester United in 2022 after blowing her ACL out. Harriet Lander via Getty Images

The UEFA panel will gather insights from players, coaches, physicians, physiotherapists, and even parents. The aim is to publish a consensus on ACL injury prevention and management this year.

Even at face value, the problem is complex. Biomechanically, ACL notch width index is smaller between men and women, however, that’s not a definitive weakness.

Kellond-Knight says menstruation timing is one thing but she believes women are inherently disadvantaged, at least in Australia.

Unlike men, a lot of women compete part-time in the A-Leagues. She believes the absence of a year-long training program coupled with an increase in load as women’s football grows are contributing factors.

“It’s a four-week pre-season and we had several ACLs within the first two weeks. No-brainer, those two things are related if you only give us four weeks to train at that top level,” said Kellond-Knight.

“Everyone goes back into an NPL-level (National Premier Leagues Victoria) environment, you’re training less, you’re training less intense, you’re deconditioned, then you go back into an A-League environment, you’ve got four weeks to prepare. Of course, injuries are going to happen. Any change in load will be high risk for an injury.”

(From left) Chloe Logarzo of Western United, Elise Kellond-Knight of Melbourne Victory, Kyah Simon of Central Coast Mariners, and Cortnee Vine of Sydney FC pose during the A-Leagues season launch. Mark Metcalfe via Getty Images

Ironically, the game’s rapid growth is to the detriment of its players in Kellond-Knight’s view.

“Players are playing a lot more minutes than what they were previously conditioned to. Men who have years to develop and adapt to that so I think stuff like that ties into that,” she explained.

Ultimately, Kellond-Knight yearns for more female-focused research. Training models and data, she said, are mostly male-based.

Even something as simple as a football boot and stud pattern designed specifically for women would be, for lack of a better term, a step in the right direction.

There are positive signs, however. The sheer volume of ACL injuries has governing bodies and football clubs taking action.

“FIFA has started an initiative where they’re specifically looking at the female ACL. A lot of money is being put into it,” said Kellond-Knight.

“There has been a lot of research on this at the end of the day with too many variables. Finally, people are starting to take it quite serious.

“A lot of the clubs are looking at hormone levels as well. Like things that haven’t been looked at previously because they don’t relate to men. So why would anyone investigate hormone levels in sport because only men play sport? We didn’t care about that, but now that the female game is professionalized and actually have to take into consideration the female cycles, like what happens in the body.

“Also like small things like boots are made for men. So are they trialling and testing football boots in females? No, they’re not. So when will we get a different stud pattern to men that will accommodate for our hips, knees, et cetera? Stuff like that needs to start changing.”

Elise Kellond-Knight will be part of Stan Sport’s talent line-up for the Paris 2024 Olympic Games.