The announcement of the N.F.L.’s opening matchup is meant to be a curtain raiser for the regular season. But when this year’s season opener was announced in May, the participants were the ones who raised their eyebrows.

As is the norm, the first game will feature the reigning Super Bowl champions, the Kansas City Chiefs. But the schedule makers decided not to pit the team against a storied rival or a vanquished opponent from last season’s playoffs. Instead, Kansas City will open the N.F.L. season on Thursday night against the Detroit Lions, another small-market team.

Their selection was a head-scratcher, even for the Lions. The team won eight of 10 games to end the 2022 season, but Coach Dan Campbell figured the league picked his team, in part, because it would be just competitive enough against a Kansas City team that would be the real TV draw.

“If I’m being totally honest with you about why they would give us Kansas City, yeah, well, you finished the year a certain way but they’re also betting on we won’t get” blown out, Campbell said in May.

The choice of opponent was a sign of the N.F.L.’s increasingly analytical approach to creating its 272-game regular-season schedule. For more than a century, the league relied on a balance of instinct, common sense and computers in slating games. But seismic shifts in pro football, and the way it is consumed, have complicated matters.

The N.F.L. added an extra game to the season for each team in 2021, the same year new media deals increased revenues and the number of platforms that broadcast matchups.

Besides inking a seven-year deal with YouTube in December for the rights to stream out-of-market games this season, the league has expanded flexibility to reschedule games as needed to dole out compelling matchups to CBS, Fox, Amazon Prime, NBC, Peacock, ABC and ESPN. The league has also added games in unusual time slots, including a tripleheader on Christmas Day, a first; a game on Black Friday; and games on some Saturdays. Regular-season games will be played in the United States, Germany and the United Kingdom.

To appease companies that have collectively spent more than $110 billion on rights fees, and to manage existing variables like travel and other major TV events, “the problems have just gotten bigger and harder to solve,” said Mike North, who took over as the chief scheduler this year. “There’s a lot of people that are counting on us, and we owe everybody.”

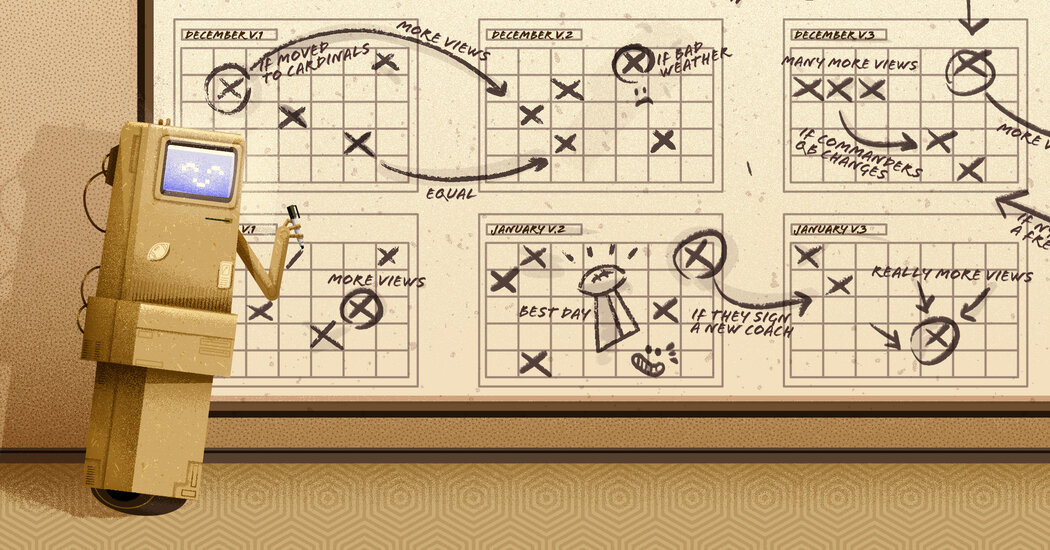

As soon as the Super Bowl ended in February, the N.F.L. used high-powered computers that produced a quadrillion possible schedule combinations. To create this season’s calendar, the league relied on Amazon Web Services, as well as software from Optimal Planning Solutions, a Canadian company, and Recentive Analytics in Boston. Recentive’s software collects data from 1,200 sources, including Airbnb, Amtrak, gambling sites, jersey sales, ticket data and non-football events on television to determine demand for a game.

“Demand for a football game is very much an equation about football demand on its own, plus demand for everything else,” Andy Tabrizi, a founder of the company, said. “We really focus on a combination of things that are directly tied to football and behaviors that may not seem like they do but impact people’s time, money and awareness.”

Abandoning its longtime approach of manually blocking out pro football’s traditional anchors, like Thanksgiving Day matchups and division rivalries in the last weeks of the regular season, the N.F.L. instead focused on producing the highest overall viewership for the season across all platforms, not just prime-time broadcasts on the free over-the-air TV networks.

It fed to its computers dozens of variables that could affect demand for certain teams in certain time slots, including recent trades of certain players, like Aaron Rodgers, and the preferences of the teams and broadcasters.

“We find the most important, most interesting games first, and then solve around them,” North said. “Instead of committing to a game or two for each network right off the bat, we got a pool of games together, say the 10 or 15 best, and spread them around across our partners. Which one we might end up with who could change by the day right up until the last minute.”

The Chiefs, perhaps the team most in demand, are scheduled to play on each of the league’s media partners’ platforms, as are the Jets, who made the biggest trade of the off-season, acquiring Rodgers. They will face off in Week 4, on Oct. 1, on NBC’s “Sunday Night Football.” The league’s computers slotted the Super Bowl rematch between Kansas City and the Philadelphia Eagles for Week 11, on Nov. 20, in a “Monday Night Football” game for ESPN.

Optimizing for ratings across all platforms has beefed up Thursday night offerings, which had been plagued by bad matchups and teams that disliked playing midweek. Amazon Prime will stream a Vikings-Eagles matchup in Week 2, for example, and also has a highly anticipated rivalry, Bengals-Ravens, in Week 11, on Nov. 16.

The Sunday lineups will also see a shake-up. Games in the two afternoon time slots had been assigned based on the conference affiliation of the road team, with visiting A.F.C. teams shown on CBS and visiting N.F.C. teams on Fox. That meant CBS had almost as many New England Patriots games as Fox had Dallas Cowboys games, the most popular teams boosting those broadcasts.

The league now has the flexibility to reassign games at 4:25 p.m. Eastern, the more watched Sunday afternoon slot, regardless of the broadcaster. The N.F.L. uses Recentive’s software during the season to determine which games to move, or flex, into prime time.

Beyond the Kansas City-Detroit matchup, Week 1 underscores league priorities. The 1 p.m. matchups seem randomly generated (Texans vs. Ravens! Cardinals vs. Commanders!), with the league slotting a storied rivalry (Packers vs. Bears) later in the afternoon, a salty divisional match (Cowboys vs. Giants) in prime time and the jewel of the first week — Bills vs. Jets — in the coveted “Monday Night Football” window.

With intriguing matchups more in demand than ever, computer modeling leaves less room for network executives to lobby N.F.L. officials for specific games. “It makes sense because everyone’s going to have a competing claim that they’re as important,” said Michael Nathanson, a media analyst at MoffettNathanson. “When you slice the packages as much as the league has sliced them, and the networks are paying what they’re paying in light of the challenges in linear television, people do have a higher claim in their eyes for getting better games.”

The data-first approach is a far cry from the 1970s, when Val Pinchbeck, a longtime league executive, manually created the schedule using tags for each team that he hung on a peg board to fill out what was then a 224-game jigsaw puzzle.

Some network executives said that in years past, they had a good sense of the biggest matchups they would broadcast a few weeks before the schedule was announced. While they rue the new, more data-driven approach, they recognize how hard it is to create a schedule that evenly distributes the most sought-after matchups while avoiding bad games in prime time.

Still, some networks are delighted with how the league has distributed the games, at least this year.

“Our schedule this year is better than it’s ever been,” Sean McManus, the chairman of CBS Sports, told reporters last week. McManus was particularly happy that CBS would broadcast eight Chiefs games and eight with the Jets.