During the March international break last season, when Arsenal’s schedule finally let up following a gruelling run of fixtures, Mikel Arteta took a trip back to his hometown of San Sebastian.

It was an opportunity to disconnect, if only briefly, from the pressures of a Premier League title challenge, and to celebrate his 41st birthday quietly in the company of friends and family.

But Arteta also made time, as he always does, to check in on Antiguoko, the amateur youth club where his footballing career and those of so many others began, taking his sons to an artificial pitch on the edge of the city to watch their U15s play Real Sociedad.

“When he comes here, he calls me,” Roberto Montiel, Arteta’s former coach and now Antiguoko’s vice-president, tells Sky Sports with a smile. “It was his birthday, but we were there at the pitch watching the game, chatting about Arsenal’s season.”

Arteta even stuck around afterwards. “The game finished at 1.30pm and his flight back to London was due at 4pm, but he took pictures with everyone, despite being in a hurry to get to the airport,” adds Montiel. “He made sure nobody missed out.”

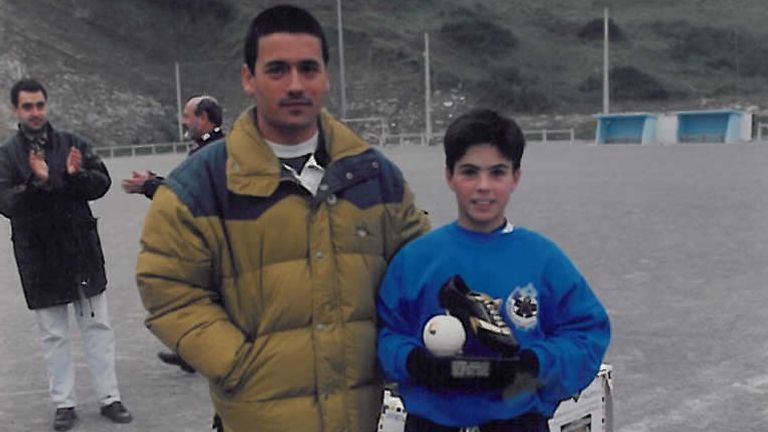

Arteta spent his formative years with Antiguoko, from the ages of nine to 15. He has always been eager to give something back. As a teenager at Barcelona, he even asked for training kits to be supplied to his boyhood club when signing his first boot deal with adidas.

“Antiguoko is just a local club, so for a player like Mikel to do that for us was special,” says Montiel. “We have had a very good relationship ever since. He has never forgotten his beginnings.”

Arteta, together with Unai Emery, Julen Lopetegui and newly-arrived Bournemouth head coach Andoni Iraola, is now one of four Premier League managers from that northern corner of Spain.

The quartet are linked not just by being from the Basque Country, but specifically from Gipuzkoa, one of the three provinces within it and the third-smallest in the entire country in terms of area.

If it is not remarkable enough that nearly a quarter of the Premier League’s current crop of managers come from a province of Spain roughly equivalent in size to Surrey, Arteta and Iraola’s connection, as former Antiguoko team-mates, is even stronger.

It does not end there, either.

That same Antiguoko team contained Xabi Alonso, another Gipuzkoa native who enjoyed a stellar playing career before moving into management, and who might also have ended up in charge of a Premier League club this season had Tottenham been successful in their efforts to prise him from Bayer Leverkusen.

“It’s amazing that there are five top-level managers who come from Gipuzkoa, but it’s even more amazing that three of them came through our club,” says Montiel.

“We have spent a lot of years developing players. Right now, we have 250 playing in Spain’s third division and up.

“And these players, they aren’t just starting out here as boys. Xabi Alonso and Iraola didn’t leave us until their juvenil (U18) years. Arteta was a second-year cadete (U15) when he went to Barcelona.

“So, really, their entire professional formation happens here.”

‘It’s amazing they are even known’

Arteta was their star- “his quality was brutal,” says Montiel – but he is not only one who retains a close bond with the club now.

Alonso, a close friend of Arteta’s since childhood, has been a recent visitor too. Iraola even returned in a coaching capacity, working with Antiguoko’s U18s while studying for his UEFA Pro Licence.

“I started my playing career there, but also my coaching career,” Iraola tells Sky Sports. “They are doing very good things. It’s amazing that they are even known. They are a really, really small club from San Sebastian. But, among academies, they are a big club.”

Antiguoko only run teams up to U18 level but their track record in player development, despite their amateur status and modest resources, has earned them a reputation to rival the biggest clubs in the region, namely Real Sociedad and Athletic Club Bilbao, who monitor their players closely and cherry pick their best talents.

“Last season, we had 14 players who signed for La Real, Athletic and Real Madrid,” says Montiel. “From our 2008 Alevin (U12) group, nine of the 16 original players are now at professional clubs.”

But Antiguoko are not just a feeder club. They are a competitive force too. Season after season, they go toe-to-toe with top-level teams in the Basque Country, its neighbouring regions and beyond.

“When we lost those players from the 2008 Alevin group, we had to bring in 13 new boys,” says Montiel. “But in the first game of the next season, we played La Real and beat them, even though half their team was made up of the players they got from us.”

Montiel’s pride is obvious and it shines through again as he reveals he has just returned from the Oviedo Cup, a prestigious youth tournament in nearby Asturias where Antiguoko’s Juvenil B team overcame sides from Alaves, Espanyol, Real Valladolid and Deportivo La Coruna to lift the trophy.

“We were the only club there that wasn’t professional, and yet we ended up as champions,” he beams.

It is just the latest example of Antiguoko punching above their weight. So, how does Montiel explain it?

“I think the demands we put on the kids from a young age, and the idea of discipline that we have at the club, is what helps them to grow,” he says. “A lot of players who leave us at 18 or younger, they say it’s not the same at their next clubs.

“In the same way, when we speak to young players with talent and bring them into our club, they are often surprised at the beginning by how intense the training sessions are, the way we work, the way we dedicate ourselves to the players and how we coach them.

“I think this is a key thing which works in our favour. Outside, they don’t play with the same force. They don’t have the same idea of going into battle. The players who come to us from Valencia, for example, say this is a style of football which is much more aggressive, more about the body, about fighting.

“I think this has an influence. If a team from Gipuzkoa or the Basque Country plays against Real Madrid, OK, they might not win. But in terms of second balls, duels, aggression and fighting for every ball, they will always be there.”

Arteta, Iraola and Alonso carried that same work-rate and competitiveness into their playing careers and, like Emery and Lopetegui, they are now defined by the same qualities as managers.

“This is something that, in Gipuzkoa, we have in our blood,” says Montiel. “From childhood, what you are taught is to know how to compete. You can win or lose, but you must always compete.”

Iraola sees it the same way.

“I think there’s a big football culture there,” he says. “Also, the work-rate is guaranteed. We are typically hard-workers – not just football-wise. We are used to working hard and we have discipline.

“These are things that, as a manager, are valuable. But, in the end, this is a small part. From there, you have to be willing to improve every day, and be willing to prove yourself every day.”

Antiguoko’s coaches work hard to instil that attitude from an early age and Ander Murillo is another player-turned-coach to have benefitted. After rising through the ranks at Antiguoko, the former defender went on to play for Athletic Club Bilbao alongside Iraola.

“They are a club who love children and love to improve children, in order to prepare them to the next step,” Murillo tells Sky Sports.

“Listen, in our place, in San Sebastian, Antiguoko fight with Real Sociedad to sign children from very young. Then, after that, they prepare them to go professional.

“They work well, and it is also important that they have this tradition of so many players who end up being professionals, with good careers. That is a calling for more children, I think.

“But the most important thing is the love for improvement and their way of working.”

‘Football is something euphoric here’

In the cases of Arteta, Iraola and Alonso, context matters too.

The trio were born during a period in which the Basque clubs dominated Spanish football, with Real Sociedad winning back-to-back Primera Division titles in 1981 and 1982 and Athletic Club Bilbao doing the same in 1983 and 1984.

“That created a huge passion here,” explains Montiel.

“It was the first time Real Sociedad had won it. Ever since then, I think that joy and that hunger to win has been maintained.

“Football really is something euphoric for the people here. They really live it. It’s the number one.

“There is a Basque law which says children can’t only play football in school. A lot of the time, a child has to do a term of basketball and a term of handball as well. But all they really want is to play football.

“There is a huge passion for it here.

“The children are with the ball from a very young age.”

Antiguoko seek to harness that passion, but their success in player development, although unique for a club of their amateur status, comes down to the region’s identity as well as their methodology – and they are not the only ones committed to it.

Over in the neighbouring province of Biscay, Athletic Club Bilbao have famously maintained top-flight status for 94 consecutive years despite only using players from the surrounding Basque Country.

Real Socieded, although more flexible in their approach, are similarly-minded, securing a Champions League finish in La Liga last season with a first-team squad containing 17 academy graduates.

But back at Antiguoko, they would be quick to point out that four of those 17 academy graduates – including key figures Martin Zubimendi and Igor Zubeldia – were Antiguoko players first.

And so the extraordinary production line continues.

With the same discipline, competitiveness and hunger to improve as Arteta, Iraola and Alonso, perhaps Zubimendi and Zubeldia, too, will one day take the talents honed at Antiguoko into management.