Any time a pitcher throws a perfect game, as Domingo Germán of the Yankees did on Wednesday, the list of previous pitchers who performed the feat is trotted out. The names are famous (Sandy Koufax! Cy Young!) and decidedly less famous (Dallas Braden?).

At the top of that list, and fairly easy to scroll past, are a pair of names separated from the others by nearly 25 years — and huge differences in game play.

1. Lee Richmond, Worcester, 6/12/1880

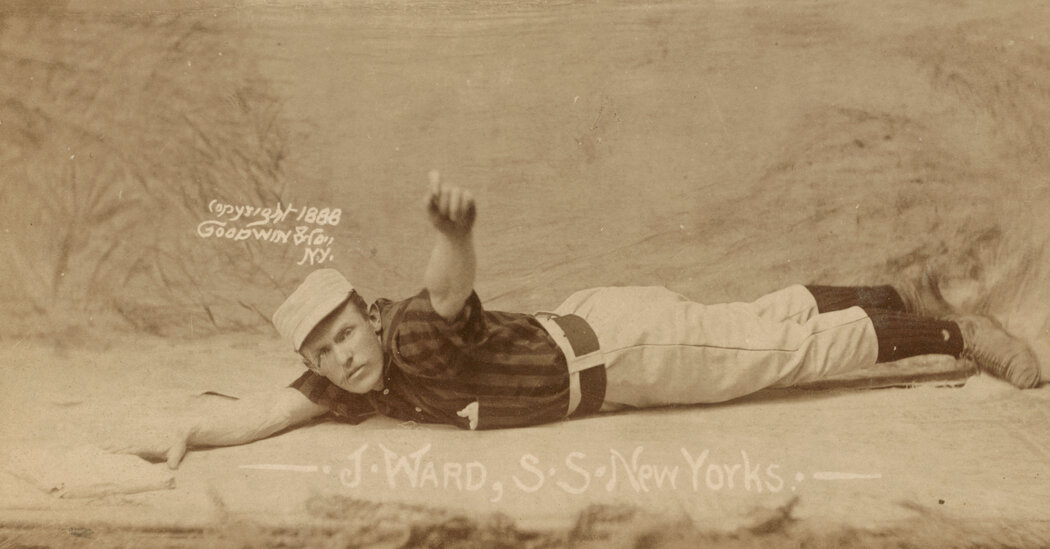

2. John Ward, Providence, 6/17/1880

Beyond the list of perfect games, their names aren’t familiar to modern audiences. Even their clubs are defunct. In some ways it can seem as if they exist solely to be credited for having pioneered a feat that remains decidedly rare to this day. And occasionally they do not even get that, as many news outlets limit their lists to baseball’s so-called modern era, which began in 1901.

Richmond at least gets the distinction of being first, and his perfect game against the Cleveland Blues was easily the highlight of his sporting career. But if you take the time to learn about Ward, who matched Richmond’s perfection in a game against the Buffalo Bisons five days later, you will find that retiring all 27 batters he faced on a Thursday afternoon at Messer Street Grounds in Providence, R.I., was just one line on a résumé that could make even Shohei Ohtani, the two-way superstar of the Los Angeles Angels, blush.

Ohtani’s ability to pitch and hit is awe-inspiring, but Ward, who was born in 1860 and was known by many as Monte for his middle name, Montgomery, did even more. He pitched a perfect game, won a National League E.R.A. title, collected 164 wins as a pitcher and 2,107 hits as a position player, had a 111-stolen-base season, became a lawyer, organized a union, formed his own professional league and, just for fun, developed such a strong golf game that he finished second in a prestigious tournament.

Pitching and playing the field was more common in the 19th century, but John Thorn, the official historian for Major League Baseball, said in an email that Ward had stood out even among his peers — and not just for his playing.

“Versatility was indeed more common in professional baseball’s early years,” Thorn said. “But Ward was uncommonly proficient as a pitcher, as an infielder-outfielder and as an author. Unlike the ghosted biographies of figures like King Kelly or Cap Anson, Ward was a college graduate and attorney who actually wrote, in 1889, ‘Base-Ball: How to Become a Player,’ with a fine historical section.”

Ward left his own accomplishments out of his book, but even the short version of his career paints a picture of a player so outstanding that it is shocking his name isn’t better known.

A standout pitcher for Providence in his early years, Ward played the outfield and then shortstop for the New York Giants after sustaining an arm injury, helping lead that team to two championships. As Thorn once wrote, “Long before Reggie Jackson, he was New York’s Mr. October.”

Ward was a huge star of his era, and he set himself apart further by understanding the value of that stardom. He helped form a players’ union in the National League and later broke from the N.L. entirely to form the Players’ League, an N.L. rival that was so far ahead of its time it had a revenue-sharing system for its owners and did not have a reserve clause binding players to teams.

His league ultimately failed, but Ward kept moving, serving as a manager of several N.L. clubs and as a team president for the Boston Braves and then traveling the world to compete in top amateur golf competitions. In 1903, he finished second at the prestigious North and South Amateur at Pinehurst in North Carolina. The New York Times provided daily coverage of the tournament, including praise of Ward’s efforts in the final round, but did not even mention his baseball career.

That type of snub would only continue.

With a career that nearly anyone would envy, he wasn’t inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame until 1964, nearly 40 years after he died. And even upon receiving that honor from the old-timer’s committee, he went mostly overlooked: The headline the next day in The New York Times named the other four players the committee had chosen, mentioning Ward only in the final two paragraphs of the story.

“Nineteenth-century worthies were largely overlooked after Anson, Kelly and Ewing got in,” Thorn said of Ward’s long wait. “One-time ‘immortals’ were consigned to the dustbin.”

Looking back at Ward’s ideas for the game, particularly in terms of how the Players’ League was organized, it should come as no surprise that he had thoughts on how to build the sport — still hyphenated as base-ball at the time — into something even bigger and better.

One of the ideas he presented in his book, which is still in print thanks to the Society for American Baseball Research, continues to resonate when you consider that baseball’s biggest issues are its aging fan base and the fact that many of the best athletes in the United States choose to play other sports.

As Ward eloquently wrote:

“The only thing now lacking to forever establish base-ball as our national sport is a more liberal encouragement of the amateur element. Professional base-ball may have its ups and downs according as its directors may be wise or the contrary, but the foundation upon which it all is built, its hold upon the future, is in the amateur enthusiasm for the game. The professional game must always be confined to the larger towns, but every hamlet may have its amateur team, and let us see to it that their games are encouraged.”