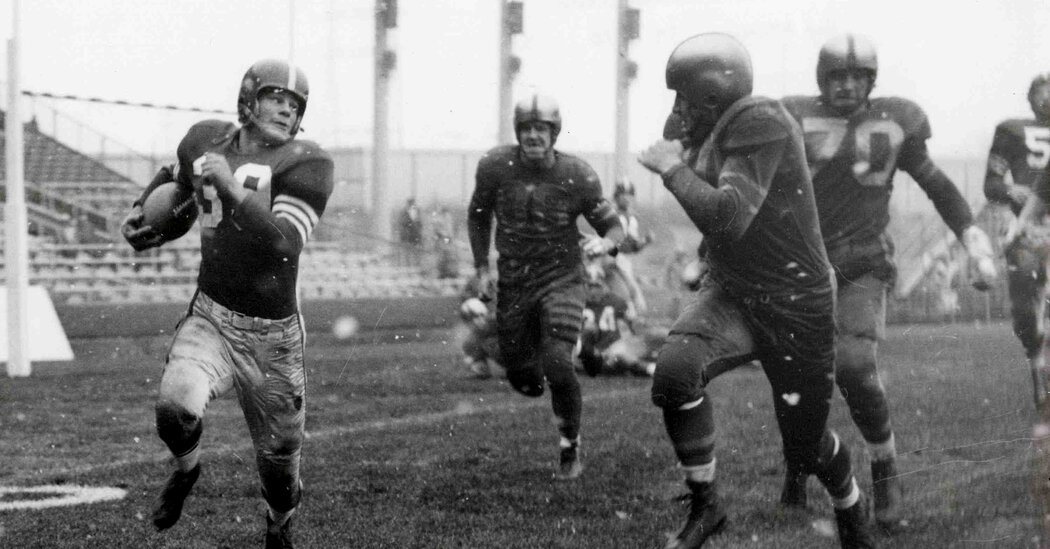

Hugh McElhenny, a Hall of Fame halfback who was known as the King for his thrilling, high-stepping prowess in the football world of the 1950s, first with the University of Washington and then with the San Francisco 49ers, died on June 17 at his home in Henderson, Nev. He was 93.

His daughter Karen Lynn McElhenny confirmed the death on Thursday but did not specify a cause. The Pro Football Hall of Fame also announced the death on Thursday.

McElhenny was a dazzling figure on the field, twisting and turning as he eluded frustrated defenders on his circuitous romps to the end zone.

“Hugh McElhenny was as good an open-field runner as you’ll ever see,” his teammate Joe Perry, the 49ers’ Hall of Fame fullback, once said.

“I was best running up the middle, and Hugh was a great outside runner who would zig and zig all over the place,” Perry, one of pro football’s first Black stars, was quoted as saying by Andy Piascik in “Gridiron Gauntlet” (2009), an oral history of the game’s racial pioneers. “Sometimes he zigged and zagged so much that the same guy would miss him twice on the same run.”

McElhenny was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1970 and the College Football Hall of Fame in 1981. He was also named to the N.F.L.’s all-decade team for the 1950s.

At 6-foot-1 and about 200 pounds, he set a host of rushing records for the Washington Huskies, of the Pacific Coast Conference. As a junior he ran for 296 yards and scored five touchdowns in a victory over Washington State. As a senior, in 1951, he ran back a punt 100 yards against Southern California. He was an All-American for a team that won only three games that season.

By his telling, he was well paid for his collegiate exploits. In an interview with The Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 2004, he said that while playing for Washington he had regularly received cash payments and other improper benefits from alumni and team boosters totaling close to $10,000 a year (about $115,000 in today’s money).

“I know it was illegal for me to receive cash, and every month I received cash,” he said. “I know it was illegal to receive clothing, and I got clothing all the time from stores. I got a check every month, and it was never signed by the same person, so we never really knew who it was coming from. They invested in me every year. I was a movie star up there.”

The 49ers selected McElhenny as a first-round draft pick and signed him to a $7,000 contract, which meant that he was getting a pay cut to play pro football.

McElhenny said he got his nickname, the King, from the 49er quarterback Frankie Albert after running back a punt for a 94-yard touchdown against the Chicago Bears in his fourth pro game.

“Albert gave me the game ball and said, ‘You’re now the King,’” he recalled in Joseph Hession’s book “Forty Niners: Looking Back” (1985). (The College Football Hall of Fame compared him to another celebrity known as the King, saying McElhenny was “to pro football in the 1950s and early 1960s what Elvis Presley was to rock and roll.”)

McElhenny was the N.F.L.’s rookie of the year in 1952, averaging seven yards a carry. Two years later, when he averaged eight yards per run, Albert’s successor at quarterback, Y.A. Tittle, and three others — McElhenny and John Henry Johnson at halfback and Perry at fullback — were collectively nicknamed the Million Dollar Backfield for their offensive power. All four were ultimately elected to the Hall of Fame.

McElhenny played in six Pro Bowls, was twice a first-team All-Pro and amassed 11,375 total yards — running, catching passes and returning punts, kickoffs and fumbles — in his 12 years in the N.F.L.: nine with the 49ers, two with the Minnesota Vikings, the 1963 season with the Giants and a final year with the Detroit Lions.

Hugh Edward McElhenny Jr. was born on July 31, 1928, in Los Angeles to Hugh and Pearl McElhenny. He was a football and hurdling star in high school, then played one season at Compton Junior College in the Los Angeles area.

He became a football celebrity at Washington, though the Huskies never made it to a bowl game in his three years there. The payments he acknowledged receiving were part of a wide scandal that led the Pacific Coast Conference to penalize Washington in 1956, along with the University of Southern California, U.C.L.A. and the University of California, Berkeley, over past illegal payments to athletes by supporters.

Following his time with the 49ers and his stint with the Vikings, McElhenny was reunited with Tittle, who had been traded to the Giants by the 49ers in 1961. Tittle took the Giants to an N.F.L. championship game for the third consecutive time in 1963 — a loss to the Chicago Bears — but McElhenny, coming off knee surgery, gained only 175 yards that year and was then released.

He was later part of an investment group that made an unsuccessful bid to obtain an N.F.L. expansion franchise for Seattle, the team that began play as the Seahawks in 1976.

In addition to his daughter Karen, McElhenny is survived by another daughter, Susan Ann Hemenway; a sister, Beverly Palmer; four grandchildren; and eight great-grandchildren. His wife, Peggy McElhenny, died in 2019.

In the spring of 1965, Frank Gifford, McElhenny’s collegiate rival when he played for U.S.C. and later his Giants teammate, threw a retirement party for him and narrated film clips of McElhenny’s spectacular jaunts, including perhaps his most famous one: the 100-yard punt return for Washington against U.S.C.

McElhenny had ignored his coach’s pleas that he let the football go into the end zone for a touchback, giving Washington the ball on the 20-yard line.

“Our coach, Howie Odell, was running down the sideline yelling, ‘Let it go, let it go!,’” he told The Seattle Times. “All of a sudden he stopped yelling. It was a stupid play on my part, but it worked out.”

McElhenny once said that his running style was not something he was taught. “It’s just God’s gift,” he said. “I did things by instinct.”

Maia Coleman contributed reporting.