It took just 37 words to change the course of education for millions of women and girls in the United States. Yet the succinct language in Title IX, the landmark education law that was signed in 1972, has origins in even fewer characters.

“You come on too strong for a woman.”

That was what Dr. Bernice Sandler was told in 1969 when she applied for a permanent position at the University of Maryland, where she was already an adjunct professor. Three years later — after a class-action lawsuit on behalf of women in higher education and the sly maneuvering of a handful of lawmakers — women were given a means to ensure equal access to higher education for the first time in American history.

For its sweeping repercussions, Title IX passed with little fanfare, a notable whisper nestled between two other landmark provisions meant to bestow rights to women within a 12-month period: The Equal Rights Amendment and Roe v. Wade. Fifty years later, it appears only one of the three will remain standing.

The Equal Rights Amendment, which proposed an explicit guarantee for equal protection for women in the U.S. Constitution, was first proposed in 1923 and approved by the Senate on March 22, 1972. But not enough states ratified it within a 10-year deadline for it to be added.

Title IX was signed by President Richard M. Nixon on June 23, 1972.

Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion in the United States, was announced on Jan. 22, 1973. But it is widely believed that the decision will most likely not see its 50th anniversary. On May 2 this year, a draft opinion was leaked that suggested that the Supreme Court might overturn the earlier ruling, which would prompt laws to change quickly in numerous states.

So what has made Title IX so durable? An act of Congress and broad public support, for starters. But even though Title IX was intended to equalize college admissions, perhaps its most visible achievement has been the inclusion of women in interscholastic sports, leading to an explosion in numerous youth sports for girls.

“Everyone can relate to sports, whether it’s your favorite team or college athletic experience — sports are a common denominator that brings us together,” said Dr. Courtney Flowers, a sports management professor at Texas Southern University and a co-author of a new analysis of Title IX by the Women’s Sports Foundation. “Everyone knows the word but ties it to athletics.”

According to the report, 3 million more high school girls have opportunities to participate in sports now than they did before Title IX. Today, women make up 44 percent of all college athletes, compared with 15 percent before Title IX.

“There had to be legislation that opened the door and changed the mind-set,” Flowers said, adding: “Because of Title IX, there is a Serena, there is a Simone Biles.”

50 Years of Title IX

The landmark gender equality legislation, which was signed into law in 1972, transformed women’s access to education, sports and much more.

Title IX emerged as an ember from the civil rights and women’s liberation movements. But like the policies that came before Title IX, its path to success was far from certain. The key was keeping it under the radar and broad, experts said.

U.S. Reps. Edith Green of Oregon, a longtime advocate of women’s inclusion, and Patsy Mink of Hawaii, the first woman of color elected to Congress, saw the struggles that the Equal Rights Amendment had faced as it made its way through the House and Senate. As they began to craft Title IX, they attempted to do so in a way that would not elicit pushback from colleagues and educational institutions.

Green and Mink considered amending the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which, among other provisions, prohibited workplace discrimination on the basis of race and sex in federally funded programs. But the path to include an education provision seemed politically difficult.

The reauthorization of the Higher Education Act of 1965, on the other hand, provided an opportunity to add a ninth title, or subset of the law, in a long list of education amendments. The act eventually turned into an omnibus education bill that dealt with antibusing policies and federal funding of financial aid for college students.

While Green and Mink decided to abandon the Civil Rights Act amendment, they did see reason to use its language.

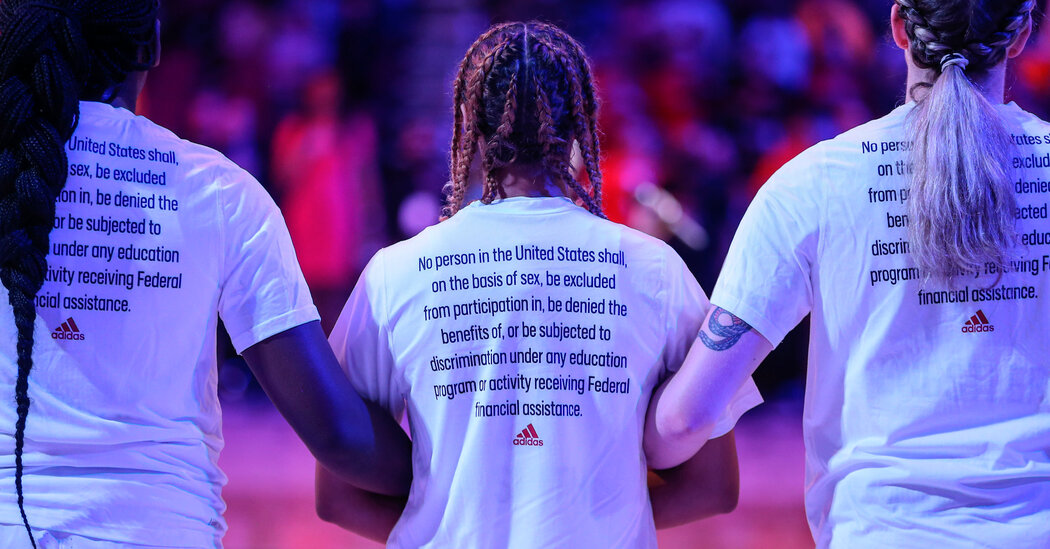

No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.

Green, Mink and other lawmakers moved forward on Title IX “not by making a huge social movement driven by an aggressive stance for education equality,” said Dr. Elizabeth A. Sharrow, a professor of history and political science at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. “They did so very subtly and quietly, and they did that on purpose because they anticipated that this idea — that we should name certain things as sex discrimination in education — could be politically contentious and they were better off finding ways to downplay it.”

It was personal for both Green and Mink, whose own experiences with discrimination influenced their policymaking. Green originally wanted to be a lawyer but was pushed into teaching by her family; Mink was denied entry to dozens of medical schools because she was a woman.

“I do think that watching her daughter be subject to the same kinds of exclusion and straight-jacketing that she had experienced as a child and as a young adult trying to carve her way forward, seeing it happen all over again, was a real motivating factor for her to try to figure out a way to try to make equality the standard and discrimination declared the wrong,” said Wendy Mink, Patsy Mink’s daughter and a political scientist.

It was personal for Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana, too. After sponsoring the Equal Rights Amendment in the Senate, he was tasked with doing the same for Title IX. Bayh’s wife, Marvella, had also been denied equal opportunities.

“My father came to feel that that was deeply unfair,” said his son Evan Bayh, also a former Indiana Senator. “He felt that if our society was going to fulfill its potential, we couldn’t disadvantage more than half the population.”

With the thrust of the bill focused on financial aid and limiting desegregation tactics, little attention was paid to the inclusion of Title IX. President Nixon made no mention of it in his signing statement. The bill’s signing made the front page of The New York Times; Title IX received a bullet point.

While the Equal Rights Amendment had opponents like Phyllis Schlafly, who led a grass-roots conservative campaign against its ratification, and Roe v. Wade had social conservatives and religious leaders prepared to protest, immediate opposition to Title IX was minimal, according to Dr. Deondra Rose, an associate professor of public policy at Duke University who focuses on landmark social policies in the United States.

Title IX also had what Rose called a “pivotal” advantage as an education policy passed down multiple generations.

A 2017 poll by the National Women’s Law Center found that nearly 80 percent of voters supported Title IX. (A March survey by Ipsos and the University of Maryland of parents and children found that most had not heard of Title IX but believed generally that boys’ and girls’ sports teams should be treated equally.)

“It’s a hard thing for lawmakers to walk back,” Sharrow said.

The Equal Rights Amendment, Roe v. Wade and Title IX are all linked by their attempts to target gendered inequality in American society, Sharrow said, but they differ in how they used law and policy to enact change.

The Equal Rights Amendment was an attempt to amend the Constitution, a process that is intended to be very difficult. Yet had it been ratified, Sharrow said, “It would have been far more sweeping than any other single policy.”

Roe v. Wade, conversely, was an interpretation of constitutional law, as a decision by the Supreme Court.

Title IX’s advantage, Rose said, was that it was relatively vague, which “gave the regulation a fighting chance over time.”

That’s not to say Title IX avoided criticism. As soon as it was signed into law, the question of enforcement “unleashed torrential controversy,” Wendy Mink said, primarily over athletics and physical education. The outcry began in early 1973, around the time of the Roe decision. Prolonged discourse over enforcement guidelines, which were finalized in 1979, focused on the debate over whether sports were a proper place for women.

“As backlash, they fed on each other — the backlash against women’s bodily sovereignty and the backlash against women being able to use their bodies in athletics,” Mink said.

The expansiveness of Title IX also created a broad umbrella for protections, including against campus sexual harassment and assault. A group of women at Yale in 1977 made sure of that with a lawsuit that led to the establishment of grievance procedures for colleges around the country.

“Title IX is excellent — we’re subjects, we’re not objects anymore,” said Dr. Ann Olivarius, one of the lead plaintiffs in the Yale lawsuit and a lawyer specializing in sexual misconduct. “We’re actually participators, we are active narrators of our own life with our bodies and we know that we actually have bodies and we use those bodies.”

Just as it met the moment in 1972, Title IX has evolved to meet a more inclusive society. In 2021, the Education Department said it planned to extend Title IX protections to transgender students. (The Biden administration has yet to finalize its proposals.)

Eighteen states have enacted laws or issued statewide rules that restrict participation in girls’ sports divisions by transgender girls, and a group of 15 state attorneys general urged the Biden administration in April to reconsider its interpretation of Title IX.

“We’re seeing these policies and the necessity of moving beyond a very narrow definition of understanding of a policy like Title IX,” Rose said. “Some people are working to use Title IX to restrict and confine, and that’s out of step with the intention of the policy.”

While the 50th anniversary of the law’s passage is a moment to celebrate, experts said, it is also a moment to consider what Title IX has not addressed. Access to college sports has progressed, but inequity remains. Other elements besides sex, including race and disabilities, are not included in Title IX’s language.

“Yes, we celebrate, but, boy, we still have work to do,” Flowers said.

The Women’s Sports Foundation found that men have nearly 60,000 more opportunities in college sports than women have. Women in college sports also lag behind male counterparts in scholarships, recruiting dollars and head coaching positions. Women of color in particular are still trailing behind their white peers — only 14 percent of college athletes are women of color.

Most experts agree that Title IX, given its widespread support, is not likely to meet similar fates as the Equal Rights Amendment or Roe v. Wade. If and how Title IX could be weakened “is in the eyes of the beholder,” said Libby Adler, a constitutional law professor at Northeastern University.

“I don’t see it being struck down. I can’t imagine what that would look like,” Adler said. “Never say never, but that’s unimaginable to me.”

However, on the issue of transgender athletes and other classes not explicitly defined in the language, Adler said Title IX could be interpreted differently.

“It’s that elasticity or indeterminacy that makes it unlikely to be struck down, but much more likely to be interpreted in ways that are consistent with the politics of the judges we have,” she said.