Indeed, his athletic prowess went far beyond the moonshot blasts he launched with his right leg. “All through high school and college, I played other positions,” Guy said in his Hall of Fame enshrinement speech. “I was a good athlete and could have been a major league pitcher, or N.B.A. basketball player, but I knew God had something special for me.”

William Ray Guy was born on Dec. 22, 1949, in Swainsboro, a small city in central Georgia, and grew up in nearby Thomson. His father, Benjamin Franklin Guy, was a building contractor, and Ray helped him build and renovate houses while he was growing up. His mother, Annette (Cato) Guy, worked as a schoolteacher’s aide.

At Thomson High School, Guy’s athletic feats became the stuff of local lore. On the football team, he played quarterback, tailback, linebacker, safety, kicker and, of course, punter, averaging nearly 50 yards per punt in 1968, according to a 2017 article in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. The day after he had led the team to its second consecutive state title, he scored 39 points for the basketball team, without benefit of a preseason. That spring, he threw 15 scoreless innings in Game 1 of the state baseball semifinals.

“He was known to his teammates as Wonderboy,” John Barnett, a Thomson historian and longtime assistant coach, told The Journal-Constitution. “He literally could do it all on the field, court or diamond.”

Guy married Beverly Bentley in 1972; they divorced about 40 years later. In addition to their son, Ryan, he is survived by a daughter from that marriage, Amber Guy; his wife, Sandy (Lord) Guy; a brother, Al; and two grandchildren. He lived in Purvis, Miss., a small city outside Hattiesburg.

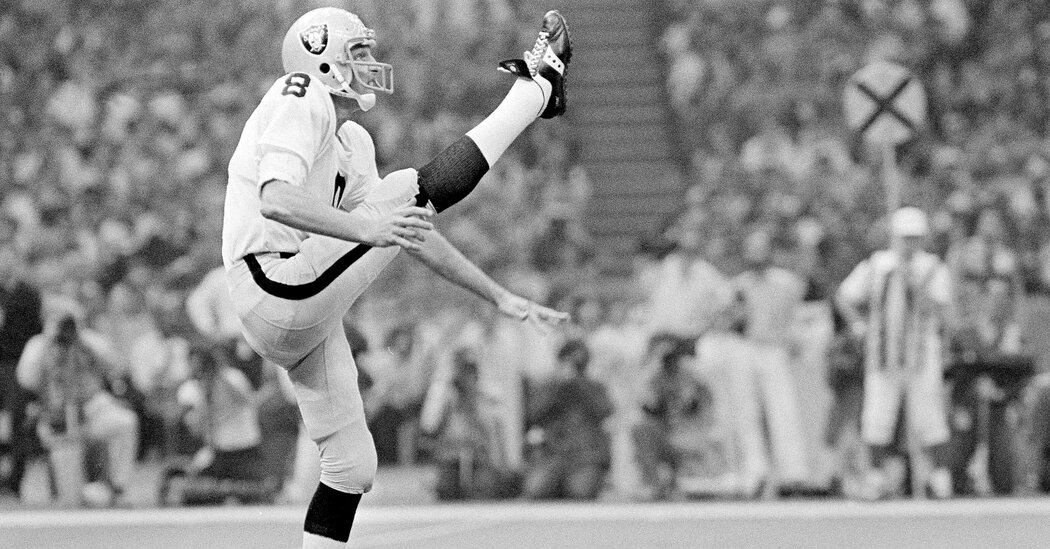

When he showed up in the N.F.L., Guy hardly looked like a future gridiron star. A clean-cut Southerner with a willowy 6-foot-3, 195-pound frame, he seemed like an odd fit with the snarling band of West Coast misfits known as the Oakland Raiders in the 1970s.

Embracing a brutal brand of football under the rebellious owner Al Davis, the team played as if doling out injuries to opponents bestowed actual points on the scoreboard, and the players were every bit as roughneck off the field. The star quarterback, Ken Stabler, once rolled up to a Sports Illustrated interview in tiny Foley, Ala., at 9 a.m. in a Chevrolet pickup, frosty beer can in hand.