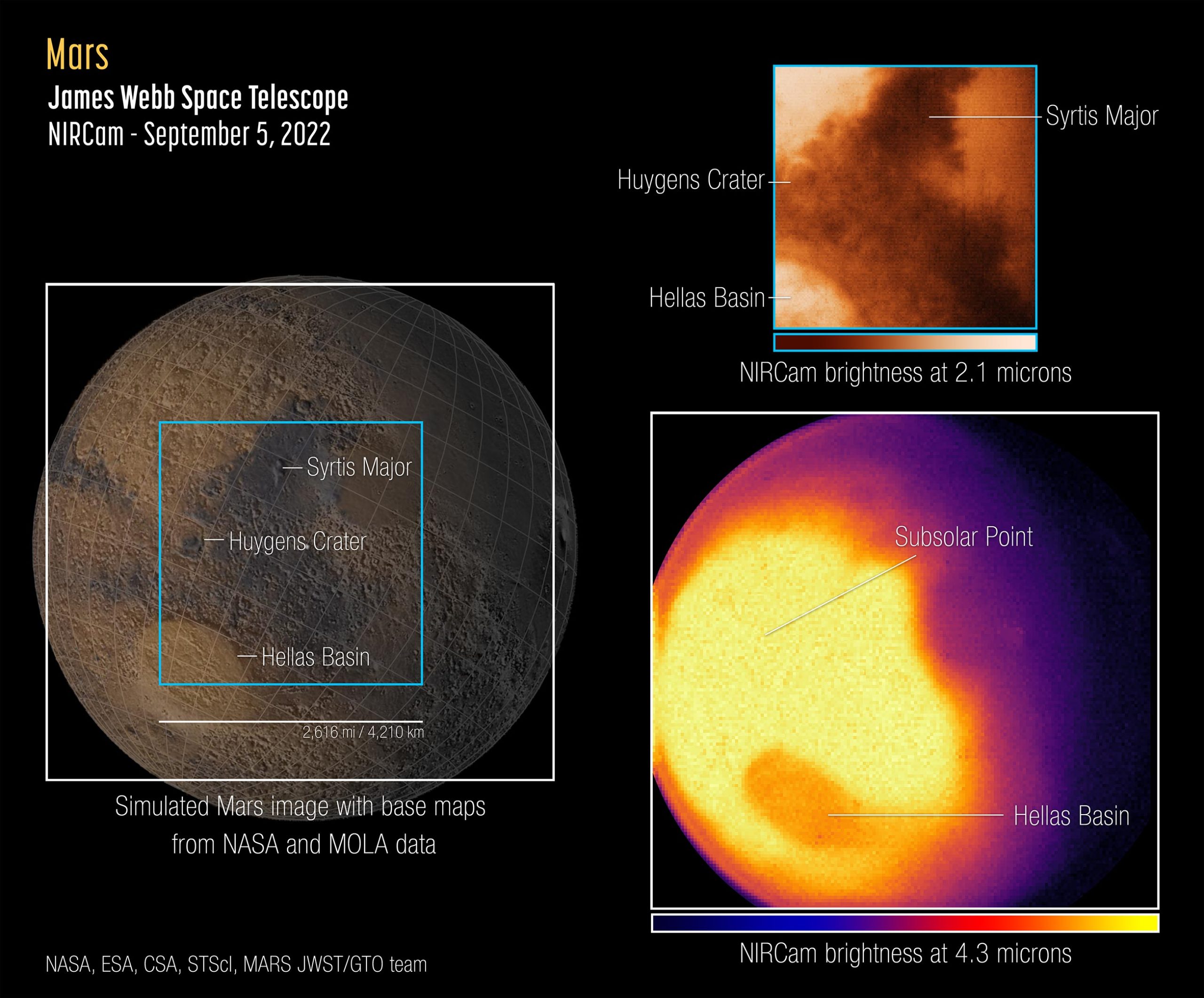

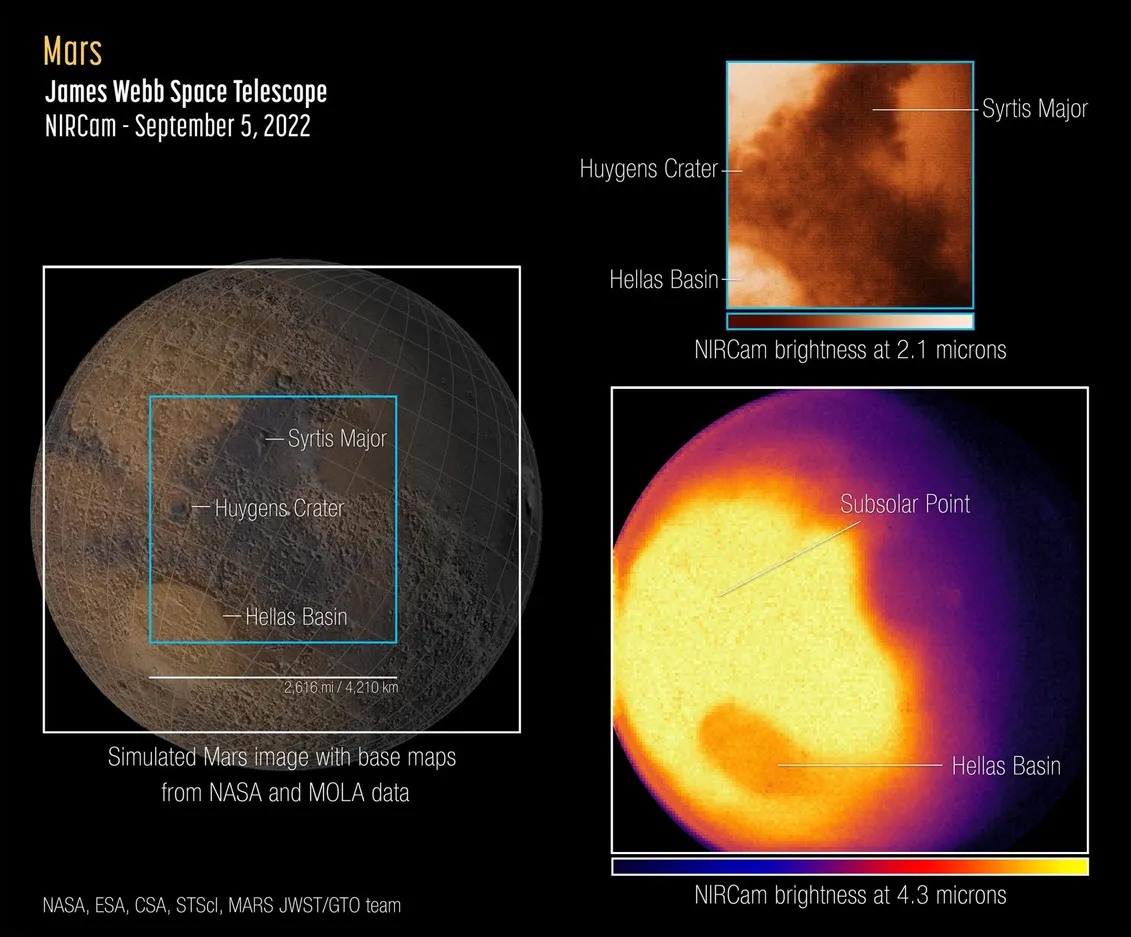

Webb’s first images of Mars, captured by its NIRCam instrument on September 5, 2022 [Guaranteed Time Observation Program 1415]. Left: Reference map of the observed hemisphere of Mars from NASA and the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA). Top right: NIRCam image showing 2.1-micron (F212 filter) reflected sunlight, revealing surface features such as craters and dust layers. Bottom right: Simultaneous NIRCam image showing ~4.3-micron (F430M filter) emitted light that reveals temperature differences with latitude and time of day, as well as darkening of the Hellas Basin caused by atmospheric effects. The bright yellow area is just at the saturation limit of the detector. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Mars JWST/GTO team

On September 5, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope captured its first images and spectra of Mars. The powerful telescope provides a unique perspective with its infrared sensitivity on our neighboring planet, complementing data being collected by orbiters, rovers, and other telescopes. Webb is an international collaboration with ESA (European Space Agency) and CSA (Canadian Space Agency).

Webb’s unique observation post is nearly a million miles away from Earth at the Sun-Earth Lagrange point 2 (L2). It provides a view of Mars’ observable disk (the portion of the sunlit side that is facing the telescope). As a result, Webb can capture images and spectra with the spectral resolution needed to study short-term phenomena like dust storms, weather patterns, seasonal changes, and, in a single observation, processes that occur at different times (daytime, sunset, and nighttime) of a Martian day.

Because it is so close to Earth, the Red Planet is one of the brightest objects in the night sky in terms of both visible light (which human eyes can see) and the infrared light that Webb is designed to detect. This poses special challenges to the observatory, because it was built to detect the extremely faint light of the most distant galaxies in the universe. In fact, Webb’s instruments are so sensitive that without special observing techniques, the bright infrared light from Mars is blinding, causing a phenomenon known as “detector saturation.” Astronomers adjusted for Mars’ extreme brightness by measuring only some of the light that hit the detectors, using very short exposures, and applying special data analysis techniques.

Webb orbits the Sun near the second Sun-Earth Lagrange point (L2), which lies approximately 1.5 million kilometers (1 million miles) from Earth on the far side of Earth from the Sun. Webb is not located precisely at L2, but moves in a halo orbit around L2 as it orbits the Sun. In this orbit, Webb can maintain a safe distance from the bright light of the Sun, Earth, and Moon, while also maintaining its position relative to Earth. Credit: STScI

Webb’s first images of Mars [top image on page], captured by the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam), show a region of the planet’s eastern hemisphere at two different wavelengths, or colors of infrared light. This image shows a surface reference map from NASA and the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) on the left, with the two Webb NIRCam instrument field of views overlaid. The near-infrared images from Webb are on shown on the right.

The NIRCam shorter-wavelength (2.1 microns) image [top right] is dominated by reflected sunlight, and thus reveals surface details similar to those apparent in visible-light images [left]. The rings of the Huygens Crater, the dark volcanic rock of Syrtis Major, and brightening in the Hellas Basin are all apparent in this image.

The NIRCam longer-wavelength (4.3 microns) image [lower right] shows thermal emission – light given off by the planet as it loses heat. The brightness of 4.3-micron light is related to the temperature of the surface and the atmosphere. The brightest region on the planet is where the Sun is nearly overhead, because it is generally warmest. The brightness decreases toward the polar regions, which receive less sunlight, and less light is emitted from the cooler northern hemisphere, which is experiencing winter at this time of year.

The James Webb Space Telescope. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

However, temperature is not the only factor affecting the amount of 4.3-micron light reaching Webb with this filter. As light emitted by the planet passes through Mars’ atmosphere, some is absorbed by carbon dioxide (CO2) molecules. The Hellas Basin – which is the largest well-preserved impact structure on Mars, spanning more than 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers) – appears darker than the surroundings because of this effect.

“This is actually not a thermal effect at Hellas,” explained the principal investigator, Geronimo Villanueva of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, who designed these Webb observations. “The Hellas Basin is a lower altitude, and thus experiences higher air pressure. That higher pressure leads to a suppression of the thermal emission at this particular wavelength range [4.1-4.4 microns] due to an effect called pressure broadening. It will be very interesting to tease apart these competing effects in these data.”

Villanueva and his team also released Webb’s first near-infrared spectrum of Mars, demonstrating Webb’s power to study the Red Planet with spectroscopy.

Webb’s first near-infrared spectrum of Mars, captured by the Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) on September 5, 2022, as part of the Guaranteed Time Observation Program 1415, over 3 slit gratings (G140H, G235H, G395H). The spectrum is dominated by reflected sunlight at wavelengths shorter than 3 microns and thermal emission at longer wavelengths. Preliminary analysis reveals the spectral dips appear at specific wavelengths where light is absorbed by molecules in Mars’ atmosphere, specifically carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and water. Other details reveal information about dust, clouds, and surface features. By constructing a best-fit model of the spectrum, by using, for example, the Planetary Spectrum Generator, abundances of given molecules in the atmosphere can be derived. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Mars JWST/GTO team

Whereas the images show differences in brightness integrated over a large number of wavelengths from place to place across the planet at a particular day and time, the spectrum shows the subtle variations in brightness between hundreds of different wavelengths representative of the planet as a whole. Astronomers will analyze the features of the spectrum to gather additional information about the surface and atmosphere of the planet.

This infrared spectrum was obtained by combining measurements from all six of the high-resolution spectroscopy modes of Webb’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec). Preliminary analysis of the spectrum shows a rich set of spectral features that contain information about dust, icy clouds, what kind of rocks are on the planet’s surface, and the composition of the atmosphere. The spectral signatures – including deep valleys known as absorption features – of water, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide are easily detected with Webb. The researchers have been analyzing the spectral data from these observations and are preparing a paper they will submit to a scientific journal for peer review and publication.

In the future, the Mars team will be using this imaging and spectroscopic data to explore regional differences across the planet, and to search for trace gases in the atmosphere, including methane and hydrogen chloride.

These NIRCam and NIRSpec observations of Mars were conducted as part of Webb’s Cycle 1 Guaranteed Time Observation (GTO) solar system program led by Heidi Hammel of AURA.