Research reveals that Britain’s earliest brass bands were established by military musicians returning from the Napoleonic Wars in the 1810s, debunking the idea that they were solely civilian and northern creations.

There is a common misconception that brass bands originated with coal miners and other industrial communities in northern England and Wales during the 1830s to 1850s. However, new findings have refuted this theory.

Dr. Eamonn O’Keeffe, a historian from the University of Cambridge, has uncovered strong evidence that Britain’s earliest brass bands were established by military musicians in the 1810s. His research, recently published in The Historical Journal, demonstrates that regimental bands began adopting all-brass ensembles shortly after the Napoleonic Wars, setting the stage for the wider adoption of brass bands across Britain.

Early Brass Bands and Military Influence

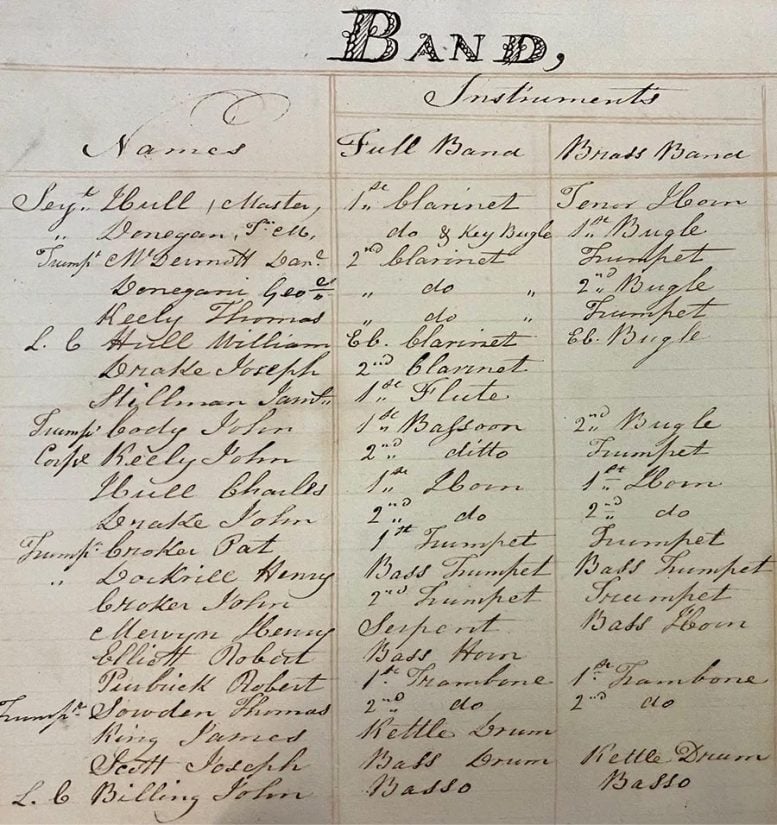

Although wartime bands included woodwind instruments such as clarinets and bassoons, O’Keeffe points out that the 15th Regiment of Foot had already organized a bugles-only band by 1818 and that numerous regiments had established all-brass bands by 1830, taking advantage of new instrument designs developed at home and in Continental Europe. The Life Guards, for example, performed on valved trumpets gifted by the Russian Czar. Local defense units also mustered brass bands, including a volunteer rifle corps in Paisley (1819) and yeomanry troops in Devon (1827) and Somerset (1829).

His research also reveals that veterans of the Napoleonic wars founded many of Britain’s earliest non-military brass bands from the 1820s onwards. These ensembles often emerged far beyond the northern English and Welsh industrial communities with which they later became associated.

The first named civilian band which O’Keeffe has identified, the Colyton Brass Band, played God Save the King in a village in Devon in November 1828 as part of birthday festivities for a baronet’s son. O’Keeffe found slightly later examples in Chester and Sunderland (both 1829), Derby and Sidmouth (1831), and Poole (1832). In 1834, Lincoln’s brass band was being trained by William Shaw, ‘formerly trumpeter and bugleman’ in the 33rd Regiment of Foot.

“These findings illustrate just how deeply brass bands are embedded in British history and culture,” said Dr. O’Keeffe, who is the National Army Museum Junior Research Fellow at Queens’ College, Cambridge, and part of the University’s Centre for Geopolitics.

“We already knew about their relationship with industrialization. Now we know that brass bands emerged from Britain’s wars against Napoleon.”

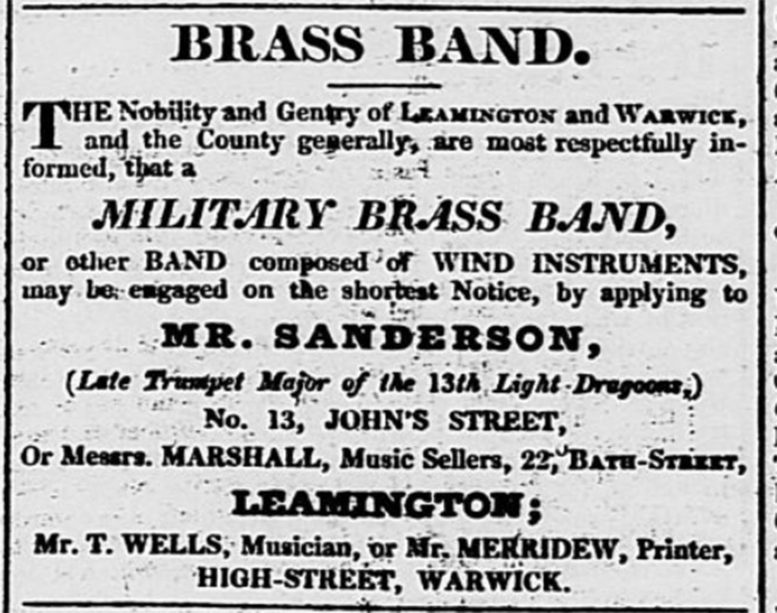

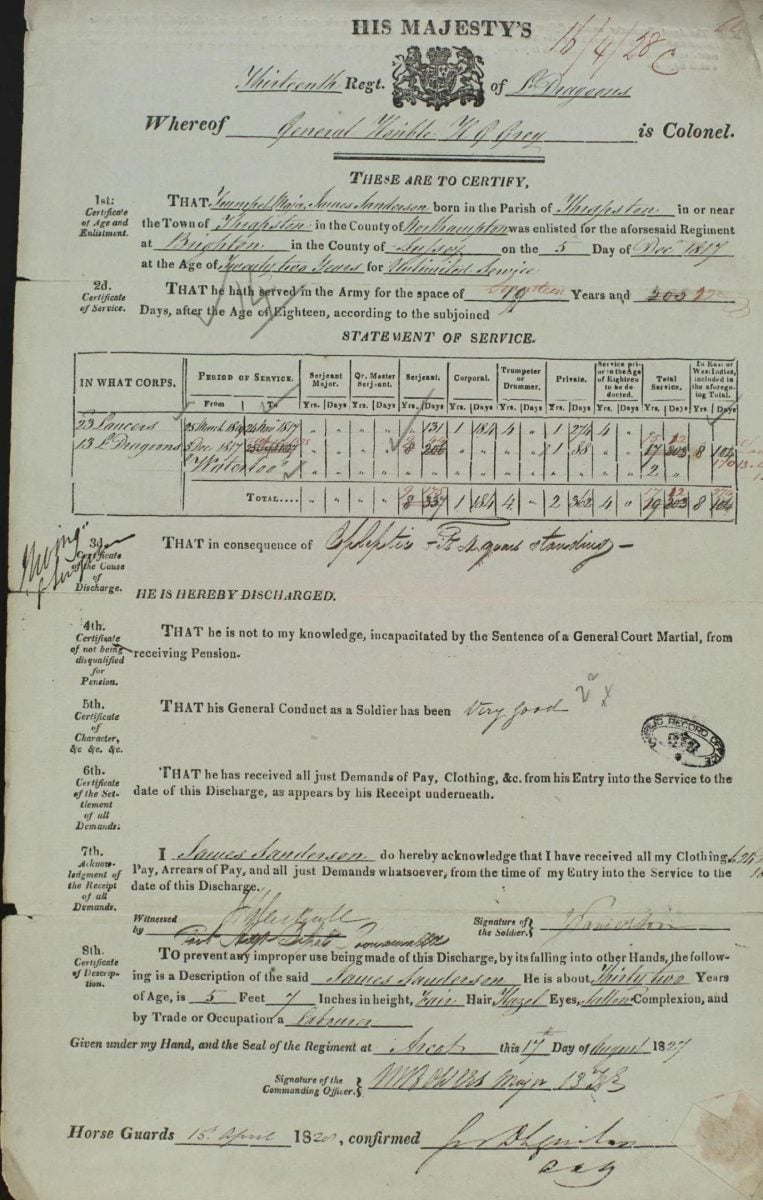

O’Keeffe discovered most about a band founded by James Sanderson, a Waterloo veteran, in Leamington Spa, Warwickshire. Sanderson, a former trumpet major, publicized his ‘military brass band’ in the Leamington Spa Courier in February 1829. Surviving newspaper reports from that summer reveal that the outfit, equipped with keyed bugles, trumpets, French horns, and trombones, performed at several well-attended fetes and other events in the area.

Sanderson’s military pension describes him as a laborer born in Thrapston, Northamptonshire. He joined the 23rd Light Dragoons, a cavalry regiment, in 1809, fought at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, and went on to become the trumpet major of the 13th Light Dragoons. He left the army due to epileptic fits in the 1820s.

On June 29th, 1829, the Leamington Spa Courier reported that ‘Sanderson’s Warwick and Leamington Military Brass Band’ performed at a Waterloo anniversary parade in Warwick. Wearing his Waterloo medal, Sanderson mustered his fellow veterans to the tune of ‘See the conquering hero comes’. On 1st July, the Leicester Herald reported that Sanderson’s band played for up to 300 people at a village feast in Stoneleigh, Warwickshire, inspiring a ‘merry dance’.

War and Peace

O’Keeffe points out that the Napoleonic Wars (1793 – 1815) led to a dramatic proliferation of British military bands. By 1814, more than twenty thousand instrumentalists were serving in uniform, in the regular army and militia, as well as a host of part-time home defense formations.

Most of those in full-time service received higher pay than regular soldiers but were still subject to military discipline. The majority were fifers, drummers, trumpeters, and buglers, whose music conveyed commands while enhancing parade-ground pageantry and morale. The remainder served in regimental bands of music, which not only enlivened military ceremonies but performed at a wide variety of public occasions, including balls, concerts, and civic processions.

By studying previously overlooked press reports, memoirs, and regimental records, O’Keeffe reveals that once demobilized, men and boys who honed their instrumental skills in uniform embarked on a variety of civilian musical careers, becoming instructors, wind performers, composers, and even opera singers.

Many performed in an array of militia and volunteer bands that remained active long after demobilization. Others instructed or participated in a growing assortment of amateur wind and all-brass bands, which often sported uniforms and consciously emulated their regimental equivalents.

O’Keeffe said: “It is widely assumed that brass bands were a new musical species, distinct from their military counterparts. They are primarily seen as a product of industrialization pioneered by a combination of working-class performers and middle-class sponsors.

“But all-brass bands first appeared in Britain and Ireland in a regimental guise. As well as producing a large cohort of band trainers, the military provided a familiar and attractive template for amateur musicians and audiences. This coincided with expanding commercial opportunities and a growing belief in the moralising power of music.”

O’Keeffe argues that these quasi-martial troupes enjoyed cross-class appeal, becoming fixtures of seaside resorts, pitheads, and political demonstrations in the decades after Waterloo, and were not confined to northern English industrial towns.

“Soldiers returned from the Napoleonic wars amidst a severe economic recession and many suffered a great deal,” O’Keeffe said. “But here we see musicians using the skills they developed in the military to survive and often thrive.”

Instrumental Legacy

The Napoleonic wars created unprecedented demand for brass and other musical instruments. As well as tracking down individual musicians and bands, O’Keeffe investigated the circulation of regimental instruments after the Battle of Waterloo.

Government-issued drums and bugles were supposed to return to public stores on demobilization and band instruments generally belonged to regimental officers. But drummers and bandsmen were often unwilling to relinquish the tools of their trade.

Seven Herefordshire local militia musicians petitioned their colonel in 1816 ‘to make us a present’ of their regimental instruments, noting that performers in other disbanded units had been permitted to keep their instruments ‘as a perquisite’. The men promised to continue their weekly practices if the request was granted, pledging that ‘a band will be always ready in the town of Leominster for any occasion’.

Some officers auctioned off the instruments of their disbanded corps, making large volumes of affordable second-hand instruments available to amateur players and civilian bands in the post-war decades.

Early brass bands also embraced new instrument designs adopted by their military counterparts or introduced by regimental and ex-regimental performers. The keyed bugle, patented by an Irish militia bandmaster in 1810, was widely used by the first generation of all-brass ensembles. The popularization of affordable and uncomplicated saxhorns by the Distin family further aided the spread of brass bands from the 1840s. The family’s patriarch, John Distin, had begun his musical career in the wartime militia.

Enduring Tunes

O’Keeffe identifies a number of tunes originating in the military that remained popular with the broader public long after Waterloo.

Theatre critics in the 1820s decried the nation’s love of ‘Battle Sinfonias’ and the ‘modern mania for introducing military bands on the stage’. ‘The Downfall of Paris’, a favorite regimental quick march, became a mainstay of buskers in post-war London. A music critic writing in 1827 lamented the neglect of Bach and Mozart in favor of this tune, which he said every piano instructor ‘must be able to play, and moreover to teach’.

But recalling his youth in Richmond, North Yorkshire in the 1820s and 1830s, Matthew Bell described the expert militia band as a ‘very popular’ source of free entertainment for poorer townspeople and claimed it aroused ‘a slumbering talent for music in some of those who heard its martial and inspiring strains.’

Writing in 1827, the Newcastle historian Eneas Mackenzie was clear that ‘The bands attached to the numerous military corps embodied during the late war have tended greatly to extend the knowledge of music. At present, there is a band belonging to almost every extensive colliery upon the Tyne and the Wear’.

O’Keeffe said: “Brass bands enabled aspiring musicians of all ages to develop new skills and allowed people to make music as a community, learning from each other. That was the case in the nineteenth century and it’s still the case today.”

Dr. O’Keeffe is writing a book about British military music during the Napoleonic Wars.

Reference: “British Military Music and the Legacy of the Napoleonic Wars” by Eamonn O’Keeffe, 30 October 2024, The Historical Journal.

DOI: 10.1017/S0018246X24000372