Traditionally, migratory birds are thought to arrive at their wintering grounds after fall migration and remain there until the spring migration back to breeding sites. This assumption forms the basis for determining over-wintering ranges and shaping conservation measures. However, a team led by scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior has discovered that over-wintering ranges may be far more dynamic.

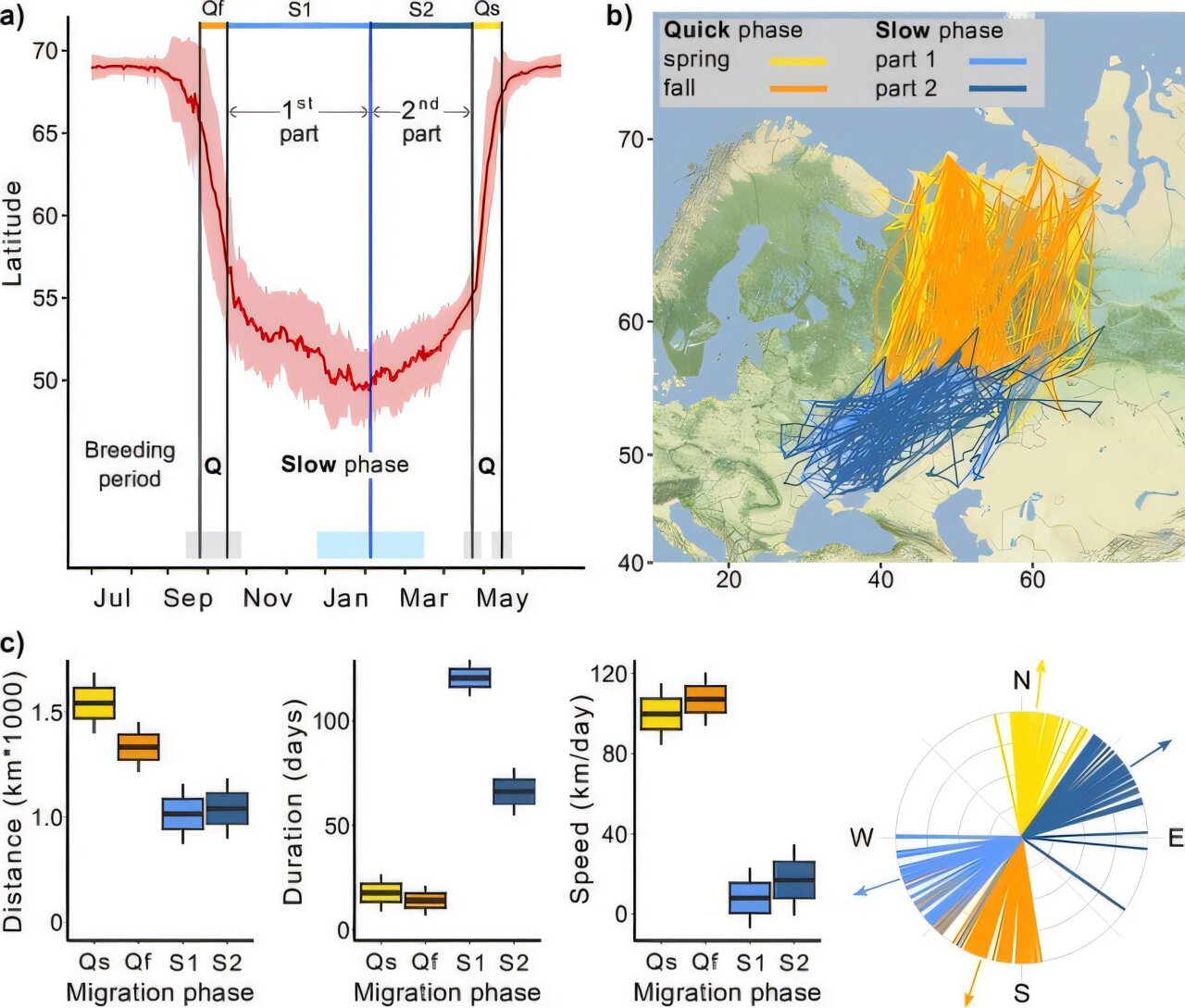

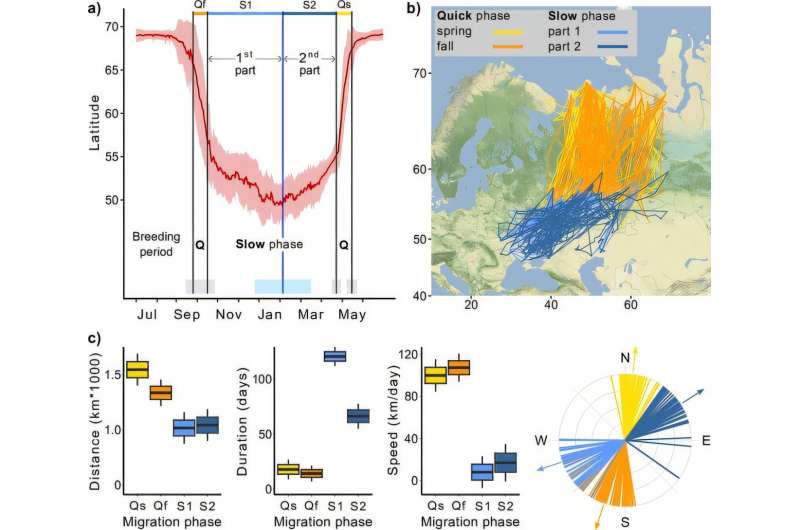

Researchers have found that the rough-legged buzzard—a raptor that breeds in the Arctic and winters at mid-latitudes—has a distinctive migration pattern. After a rapid migration to the mid-latitudes, they continue to migrate at a slower pace through the winter and then return to the Arctic at a quick pace. Because of the alternating quick and slow pace during migration, scientists have named this pattern “foxtrot migration.”

The study is published in the journal eLife.

Bird winter ranges are often determined through mid-winter surveys, such as the Christmas Bird Counts in North America or similar surveys in Europe, where scientists and volunteers observe and count birds over several days in mid-winter, mapping each species’s winter range. Knowledge about a species’s range is crucial for developing strategies to protect rare species.

“But what if birds are moving throughout winter, and regions that appear densely populated mid-winter are deserted at other times of the over-wintering period, which—for many species—spans from October to April?” asks Ivan Pokrovsky, the lead author of the study and research scientist at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior.

The team tracked the movements of Arctic-breeding rough-legged buzzards over seven years using GPS technology. They found that each fall, these birds travel approximately 1,500 kilometers in just two weeks from the Arctic to mid-latitudes. Yet surprisingly, they do not stay put. Instead, they gradually continue migrating southwest over the winter—covering an additional 1,000 kilometers at a tenth of their initial pace. Around mid-winter, they turn back and slowly retrace their route before rapidly migrating back to the Arctic in mid-April.

When mid-winter surveys are conducted, these birds are primarily found in the southwestern part of their over-wintering range. As a result, this area is classified as common or more populated, while the northeastern part is deemed uncommon. However, in reality, the situation is quite the opposite. For much of the overall over-winter period, they actually spend most of their time in the northeastern areas, only utilizing the southwestern region during mid-winter.

“Mid-winter surveys are well-suited for snapshot assessments of wintering bird populations. However, to accurately map the winter ranges of these birds, it is essential to track their movements throughout the entire wintering period,” says Pokrovsky.

Another critical finding relates to distinguishing population declines from redistribution. If a species’s numbers are decreasing in a certain region, this may suggest either an overall decline in the species or a redistribution. For example, if the numbers of a species exhibiting foxtrot migration decline in the southern parts of its over-wintering range, this could mean that the dynamics of its over-wintering range have altered, and the species is no longer reaching these southern areas, even if the overall population remains stable.

In this study, the researchers found that over-wintering range dynamics are closely linked to changes in snow cover, which may significantly vary with climate change, leading to a redistribution of populations during the over-wintering period. This distinction is crucial when assessing the conservation status of the species.

“Our study underscores the importance of year-round animal tracking. It demonstrates that, through tracking technology, animals can reveal critical aspects of their lives—information that is essential to helping them overcome the challenges for which we hold responsibility, especially in this era of environmental change and political challenges,” says Martin Wikelski, senior author of the publication and director of the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior.

More information:

Ivan Pokrovsky et al, Foxtrot migration and dynamic over-wintering range of an Arctic raptor, eLife (2024). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.87668.4

Journal information:

eLife

Provided by

Max Planck Society

Citation:

Arctic raptors study reveals a new migration pattern, highlighting potential errors in range mapping (2024, November 11)

retrieved 12 November 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-11-arctic-raptors-reveals-migration-pattern.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.