Chromosphaera perkinsii is a single-celled species discovered in 2017 in marine sediments around Hawaii. The first signs of its presence on Earth have been dated at over a billion years, well before the appearance of the first animals.

A team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has observed that this species forms multicellular structures that bear striking similarities to animal embryos. These observations suggest that the genetic programs responsible for embryonic development were already present before the emergence of animal life, or that C. perkinsii evolved independently to develop similar processes. In other words, nature would therefore have possessed the genetic tools to “create eggs” long before it “invented chickens.”

The study is published in the journal Nature.

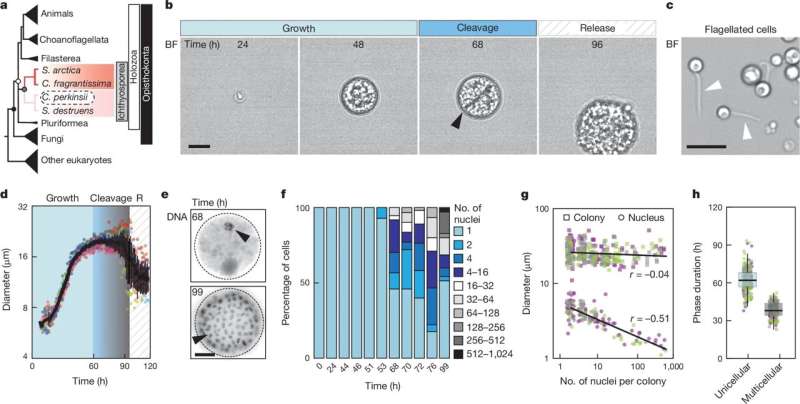

The first life forms to appear on Earth were unicellular, i.e., composed of a single cell, such as yeast or bacteria. Later, animals—multicellular organisms—evolved, developing from a single egg cell to form complex beings. This embryonic development follows precise stages that are remarkably similar between animal species and could date back to a period well before the appearance of animals. However, the transition from unicellular species to multicellular organisms is still very poorly understood.

Recently appointed as an assistant professor at the Department of Biochemistry in the UNIGE Faculty of Science, and formerly an SNSF Ambizione researcher at EPFL, Omaya Dudin and his team have focused on Chromosphaera perkinsii (C. perkinsii), an ancestral species of protist. This unicellular organism separated from the animal evolutionary line more than a billion years ago, offering valuable insight into the mechanisms that may have led to the transition to multicellularity.

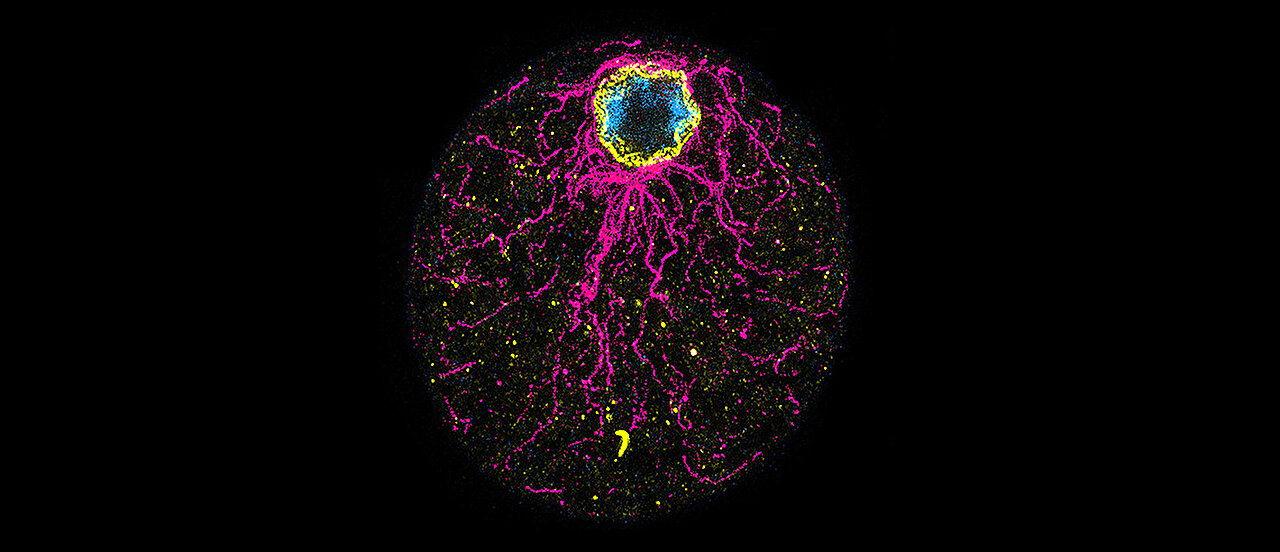

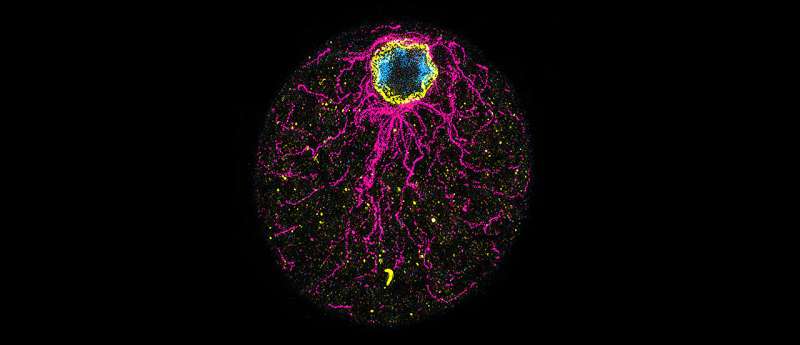

By observing C. perkinsii, the scientists discovered that these cells, once they have reached their maximum size, divide without growing any further, forming multicellular colonies resembling the early stages of animal embryonic development. Unprecedentedly, these colonies persist for around a third of their life cycle and comprise at least two distinct cell types, a surprising phenomenon for this type of organism.

“Although C. perkinsii is a unicellular species, this behavior shows that multicellular coordination and differentiation processes are already present in the species, well before the first animals appeared on Earth,” explains Dudin, who led this research.

Even more surprisingly, the way these cells divide and the three-dimensional structure they adopt are strikingly reminiscent of the early stages of embryonic development in animals. In collaboration with Dr. John Burns (Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences), analysis of the genetic activity within these colonies revealed intriguing similarities with that observed in animal embryos, suggesting that the genetic programs governing complex multicellular development were already present over a billion years ago.

Marine Olivetta, laboratory technician at the Department of Biochemistry in the UNIGE Faculty of Science and first author of the study, observes, “It’s fascinating, a species discovered very recently allows us to go back in time more than a billion years.”

In fact, the study shows that either the principle of embryonic development existed before animals, or that multicellular development mechanisms evolved separately in C. perkinsii.

This discovery could also shed new light on a longstanding scientific debate concerning 600 million-year-old fossils that resemble embryos, and could challenge certain traditional conceptions of multicellularity.

More information:

Marine Olivetta et al, A multicellular developmental program in a close animal relative, Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08115-3. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-08115-3

Provided by

University of Geneva

Citation:

Ancient unicellular organism indicates embryonic development might have existed prior to animals’ evolution (2024, November 6)

retrieved 6 November 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-11-ancient-unicellular-embryonic-prior-animals.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.