The human brain’s glymphatic system, instrumental in removing toxins, has been visualized in living people through MRI technology. This breakthrough points to potential preventive measures for Alzheimer’s disease.

- A study of five volunteers undergoing surgery confirmed the existence of channels that may help drain waste from the brain.

- The results highlight the importance of ongoing research to boost the functioning of this waste-clearance system, called the glymphatic system.

The lymphatic system, though less familiar than blood vessels, plays an essential role in keeping us healthy. This network of vessels, spread throughout the body, clears out dead cells and other waste from the bloodstream, while also helping to transport immune cells that fight infections.

For many years, scientists believed the lymphatic system did not extend to the brain. However, over the past decade or so, researchers have discovered a network of vessels in the brains of mice that contain cerebrospinal fluid. These vessels appear to connect with the lymphatic system, helping to clear toxins from brain tissue.

Studies indicate that damage to this waste-clearing network in the brain, known as the glymphatic system, due to aging or physical injury, may be linked to the development of Alzheimer’s disease and other cognitive disorders.

Observing the Glymphatic System in Action

Researchers have observed the real-time workings of the glymphatic system in mice. Studies using human brain samples taken after death found hints of such vessels. But to date, the existence of a functioning glymphatic system hadn’t been confirmed in living people.

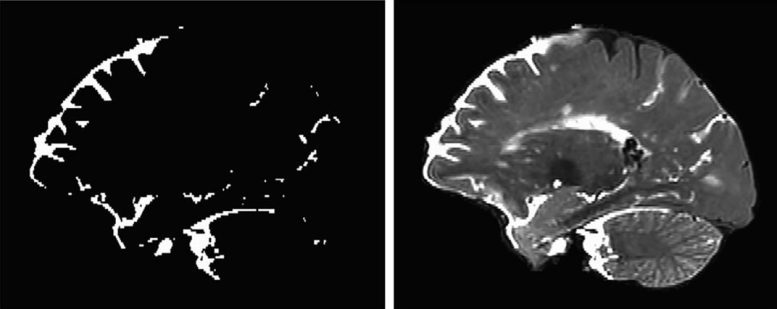

In a new study, funded in part by NIH, researchers led by Dr. Juan Piantino from Oregon Health & Science University recruited five volunteers who needed surgery to remove a brain tumor. During this surgery, the volunteers received an injection of a dye called gadolinium into their cerebrospinal fluid. They then underwent MRI scans to track the passage of dye into the brain. Results from the study were published recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

One volunteer underwent MRI using a technology called T2/FLAIR at 12 and 24 hours after surgery, and the other 4 underwent T2/FLAIR imaging at 24 and 48 hours after surgery.

MRI Imaging Reveals Brain Fluid Channels

The scans showed cerebrospinal fluid flowing into the brain through distinct channels—along the perivascular spaces, the fluid-filled spaces that run alongside blood vessels in the brain. These findings match earlier imaging results seen in mice. Dye could also be seen moving from these spaces into the functional tissue of the brain.

“This shows that cerebrospinal fluid doesn’t just get into the brain randomly, as if you put a sponge in a bucket of water,” Piantino says. “It goes through these channels.”

Potential Glymphatic System Support Through Sleep

Other studies have suggested that the glymphatic system may be most active during sleep. These new results support the importance of efforts to boost or repair the glymphatic system, such as improving sleep quality for people at risk for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

For more on this discovery, see First-Ever Images of Brain’s Secret Cleaning System Unlocks New Hope Against Alzheimer’s.

Reference: “The perivascular space is a conduit for cerebrospinal fluid flow in humans: A proof-of-principle report” by Erin A. Yamamoto, Jacob H. Bagley, Mathew Geltzeiler, Olabisi R. Sanusi, Aclan Dogan, Jesse J. Liu and Juan Piantino, 7 October 2024, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2407246121