In East Asia, a silent shift is taking place: gentrification. Urban neighborhoods are undergoing huge transformations as once-affordable areas become hotspots for upscale living.

This process, which aims to make neighborhoods more attractive to affluent residents, can force longtime residents out of their homes or neighborhoods as the places they’ve known and loved become expensive or unfamiliar.

While direct displacement has recently declined, new forms of displacement are emerging.

In a study published in The Developing Economies, Dr. Kon Kim from Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU), China, and Dr. Blaž Križnik from the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, have uncovered the intricate effects of gentrification in Seoul through a comparative analysis of two distinct urban renewal models: state-led urban regeneration and property-led redevelopment driven by the private sector.

The findings suggest that state-led urban regeneration, while appearing more inclusive, can still lead to the emotional displacement of residents who experience a growing sense of alienation from their communities even if they remain in the same neighborhood.

(In)directly displaced residents

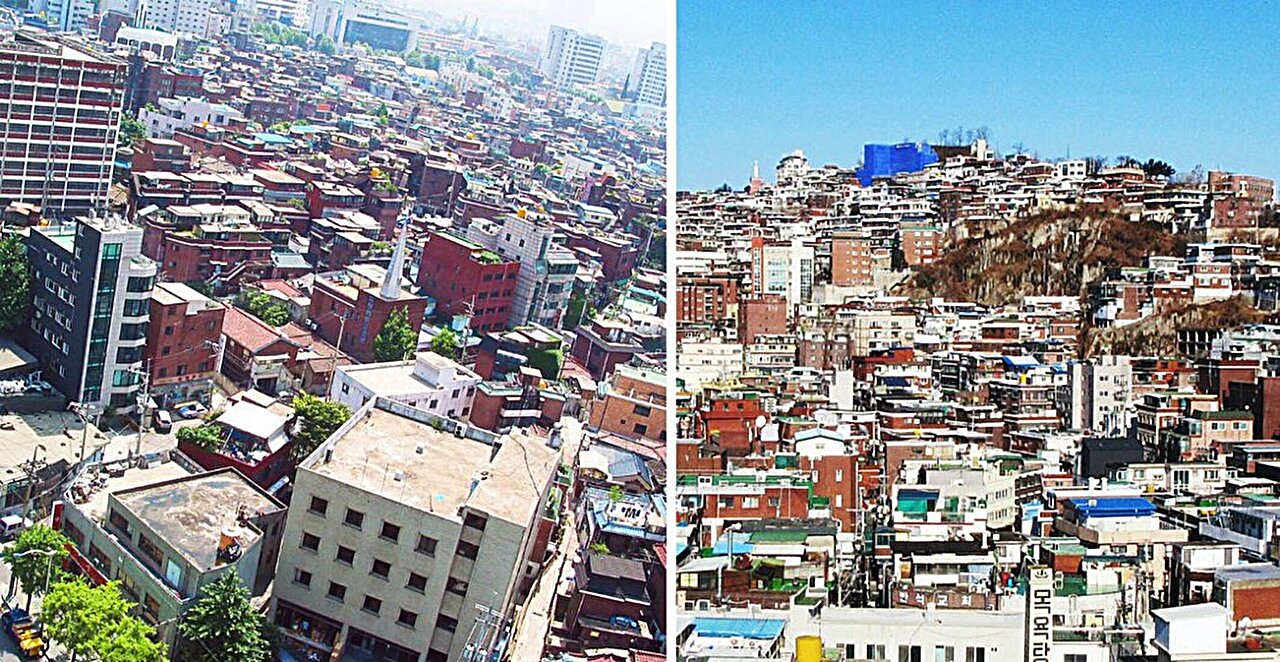

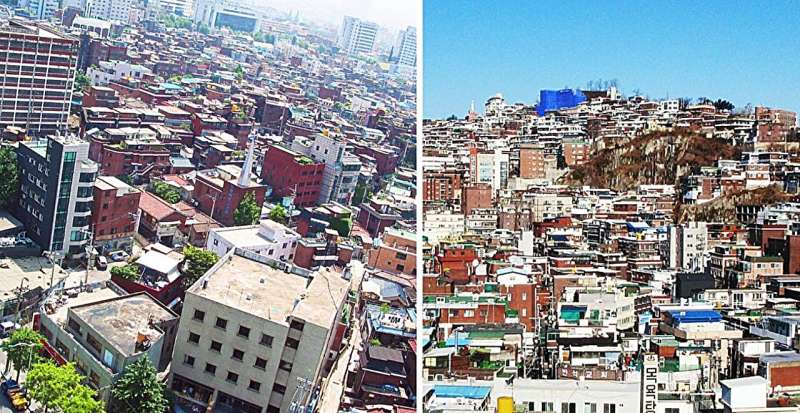

The study examines property-led redevelopment in Sangwangsimni and state-led regeneration in Changsin-Sungin and offers fresh insights into neighborhood transformation and resident displacement.

Dr. Kim says, “In the case of Sangwangsimni, we found that redevelopment led to residential gentrification, directly displacing residents and replacing the industrial clusters with large-scale high-rise residential construction.

“This contrasts sharply with Changsin-Sungin, where state-led regeneration allowed residents to remain, preserving and partially revitalizing the industrial area.

“However, even though residents remain in place, there’s a rise of indirect displacement causing them to have feelings of powerlessness and emotional distress, because their surroundings have changed significantly.”

A resident from Changsin-Sungin who was interviewed for the study said she feels like she is treated like an animal in a zoo when tourists watch or take photos of how she works in her sewing factory. However, she cannot imagine leaving the area because this has long been her place of work and life.

Another interviewee said about the regeneration: “It made me feel the kind of classy vibe of this place that never existed before. This is good for me because the new vibe sometimes lets me refresh my mind instantly.

“However, I heard that new shop owners are trying to buy other buildings and expand similar businesses. I love a few classy shops for refreshment, but do not want them overspreading our neighborhood.”

Toward more equitable urban policies

Dr. Kim says that this empirical evidence helps redefine the scope of gentrification in South Korea and broader East Asia, emphasizing indirect or symbolic displacement.

“The motivation behind our study stems from the long-standing issue of displacement in South Korea’s urban development. We aimed to address the gap in understanding the emerging forms of displacement that have not been widely discussed, even as direct eviction and displacement have declined over the past decade,” he explains.

“The study’s findings are significant not only for the academic field but also for the wider public, particularly for those affected by gentrification. It offers a clearer picture of the complex interplay between tangible and intangible factors in neighborhood transformation and displacement, providing an empirical basis for more equitable urban development policies,” adds Dr. Kim.

Dr. Kim and Dr. Križnik plan to expand their research to include state-civil society relations and grassroots resistance against state-facilitated gentrification. Their future work will explore the state’s role in facilitating displacement and the significance of grassroots movements in promoting more inclusive cities across East Asia.

More information:

Blaž Križnik et al, Changing Scope of Gentrification in Seoul? Neighborhood Transformation and Displacement in Sangwangsimni and Changsin‐Sungin Industrial Clusters, The Developing Economies (2024). DOI: 10.1111/deve.12420

Provided by

Xi’an jiaotong-Liverpool University

Citation:

Study reveals the complex impact of state-led urban change on residential communities in Korea (2024, November 1)

retrieved 1 November 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-11-reveals-complex-impact-state-urban.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.